Also by I. Bernard Cohen

Benjamin Franklins Experiments (1941)

Roemer and the First Determination of the Velocity of Light (1942)

Science, Servant of Man (1948)

Some Early Tools of American Science (1950, 1967)

Ethan Alien Hitchcock of Vermont: Soldier, Humanitarian, and Scholar (1951)

General Education in Science (with Fletcher G. Watson) (1952)

Benjamin Franklin: His Contribution to the American Tradition (1953)

Isaac Newtons Papers & Letters on Natural Philosophy (1958, 1978)

A Treasury of Scientific Prose (with Howard Mumford Jones) (1963, 1977)

Introduction to Newtons Principia (1971)

Isaac Newtons Principia, with Variant Readings (with Alexandre Koyr & Anne Whitman) (1972)

Isaac Newtons Theory of the Moons Motion (1975)

Benjamin Franklin: Scientist and Statesman (1975)

The Newtonian Revolution (1980)

An Album of Science: From Leonardo to Lavoisier, 1450-1800 (1980)

The Birth of a New Physics (Rev. & Exp. 1985)

Revolution in Science (1985)

Benjamin Franklins Science (1990)

The Natural Sciences and the Social Sciences: Some Critical and Historical Perspectives (1994)

Interactions: Some Contacts between the Natural Sciences and the Social Sciences (1994)

Newton: Norton Critical Edition (edited with Richard S. Westfall) (1995)

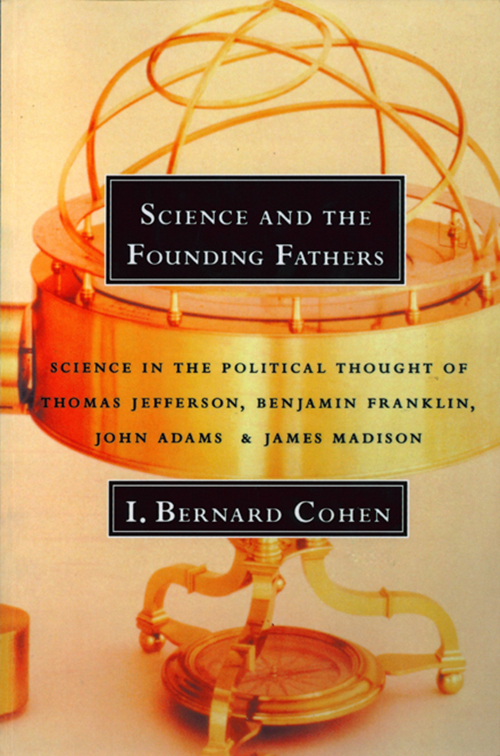

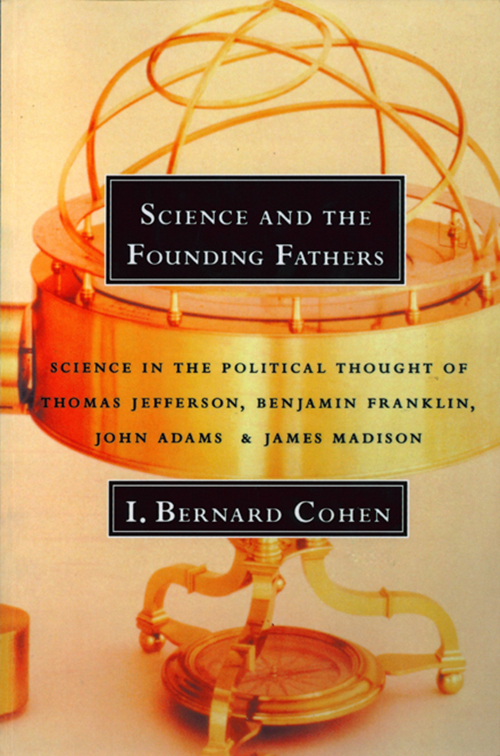

Science

and the

Founding

Fathers

Science in the Political Thought of

Jefferson, Franklin, Adams,

and Madison

.....

I. BERNARD COHEN

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

Copyright 1995 by I. Bernard Cohen

First published as a Norton paperback 1997

All rights reserved

The text of this book is composed in New Baskerville

with the display set in Caslon Open

The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group.

Book design by Chris Welch

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Cohen, I. Bernard, 1914

Science and the founding fathers : science in the political

thought of Jefferson, Franklin, Adams & Madison / I. Bernard Cohen.

p. cm.

Includes index.

I. Franklin, Benjamin, 17061790KnowledgeScience. 2. Franklin, Benjamin, 17061790Political and social views. 3. Jefferson, Thomas,17431826KnowledgeScience. 4. Jefferson, Thomas, 17431826Political and social views. 5. Madison, James, 17511836KnowledgeScience. 6. Madison, James, 17511836Political and social views. 7. Adams, John Quincy, 17671848KnowledgeScience. 8. Adams, John Quincy, 17671848Political and social views. 9. Political scienceUnited StatesHistory18th century. 10. ScienceUnited StatesHistory18th century. I. Title. II. Title: Science and the founding fathers.

E302.5.C62 1995

973.3092dc20

94-26731

CIP

ISBN-13: 978-0-393-31510-3

ISBN 978-0-393-24715-2 (e-book)

W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

W.W. Norton & Company Ltd., 10 Coptic Street, London WCIA IPU

FOR CAMBRIDGE COLLEAGUES

Bernard Bailyn

Donald H. Fleming

Lilian and Oscar Handlin

Gerald Holton

and for

Susan T. Johnson

.....

T he guiding principle of this book is the conviction that science is an important part of history, that the history of science can illuminate some of the central aspects of American history. As is often the case, this book is the product of a line of research that originally was centered on a seemingly unrelated topic, namely the different kinds of interactions that have occurred between the physical and biological sciences and the social sciences. One of the principal fruits of that research has been a volume edited by me on The Natural Sciences and the Social Sciences: Some Critical and Historical Perspectives (Dordrecht/Boston/London: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1994); my own chapters have been printed separately under the title Interactions: Some Contacts between the Natural Sciences and the Social Sciences (Cambridge/London: MIT Press, 1994), and in the Italian as Scienze della Natura e Scienze Sociali (Rome/Bari: Editori Laterza, 1993).

The social sciences treated in the above works were primarily economics and sociology, with some consideration given to theories of the state. Again and again in my research, however, I came upon examples of the ways in which political thought and even the course of political action either were determined by a scientific vector or drew on science as a source of models or of metaphors and analogies. In particular, I found that in the eighteenth century, the Age of Reason, when science was esteemed as the highest expression of human reason, the sciences served as a font of analogies and metaphors as well as a means of transferring to the realms of political discourse some reflections of the value system of the sciences. Thus James Harrington, who a century later was to become an influential figure in the political thought of the American Founding Fathers, drew on the works of the pioneer physiologist William Harvey in proposing his system of government.

For many years I have been fascinated by what I detected to be Newtonian echoes in the Declaration of Independence, a topic I have discussed again and again with the students in my graduate seminar. My researches led me to an appreciation of Jeffersons command of the technical aspects of Newtonian science and mathematics, a feature of Jeffersons thought that goes far deeper than the customary levels of discussion, which are limited to his allegiance to some form of Newtonianism or his admiration for Newton. In the end I came to recognize that science was a feature of consequence in his political thought and action.

I have studied the scientific thought of Benjamin Franklin for many decades and have long been aware of the way in which Franklins theory of demography influenced his political ideas. It was thus an easy step to consider science in relation to his political career. Ever since graduate days, I have been troubled by the alleged Newtonianism of the Constitution and have sought in vain for evidence that any part of the Constitution was a conscious or unconscious imitation of Newtonian science. In the end I discovered the source of this allegation in the writings of Woodrow Wilson. As can be seen in Chapter 5, in large measure Wilsons presentationlike those of the scholars who have repeated his argumentis based on a fundamental misunderstanding of what the science of the Principia is. My study of science in relation to the Constitution led me by a direct path to the thought of James Madison. The subject of John Adamss use of the sciences in a political context was an unexpected bonus. I was also delighted to find how the sciences were used by others of that age, such as James Wilson and Thomas Pownall.

Again and again, in the course of writing this book, I stood in awe as I faced the massive literature concerning the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and as I took cognizance of the great body of scholarly writings and textual editions relating to the careers and thought of Franklin and Jefferson, to say nothing of the growing scholarship relating to works of Adams and Madison. I had to ask myself the question recorded by Merrill Peterson in his biography of Jefferson. In the course of the work, he wrote, I have sometimes been asked, in tones ranging from curiosity to dismay, if anything important remained to be said about Jefferson. In my own case, I had to ask myself an additional question: whether an outsider who was not a specialist in American political thought, American intellectual history, or American diplomatic or social history could add anything of consequence to the monument of established scholarship and interpretation. This very question, however, defined my mission.

Next page