ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

Colin R.Johnson, Just Queer Folks:

Gender and Sexuality in Rural America

Lisa Sigel, Making Modern Love:

Sexual Narratives and Identities in Interwar Britain

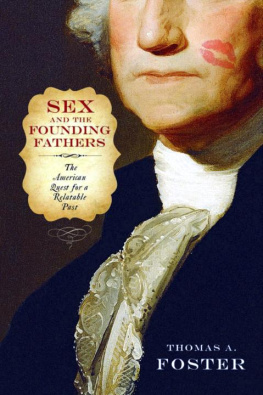

The American Quest for a Relatable Past

THOMAS A.FOSTER

LTHOUGH MY NAME ALONE appears on the cover of this book, I could never have written this volume without the time and effort that were contributed by a humblingly large number of people. What follows is my acknowledgment of a mere portion of the help I received. The earliest idea for the book came from conversations with John D'Emilio, to whom I am most grateful for his mentoring and encouragement. The support and guidance of Mary Beth Norton have sustained me throughout not only this project but also my career.

LTHOUGH MY NAME ALONE appears on the cover of this book, I could never have written this volume without the time and effort that were contributed by a humblingly large number of people. What follows is my acknowledgment of a mere portion of the help I received. The earliest idea for the book came from conversations with John D'Emilio, to whom I am most grateful for his mentoring and encouragement. The support and guidance of Mary Beth Norton have sustained me throughout not only this project but also my career.

A long list of individuals generously contributed in various ways, providing important feedback, reading drafts, and writing letters for grant applications. I especially thank Lauren Berlant, Frances Clarke, John D'Emilio, Toby Ditz, Carolyn Eastman, Estelle Freedman, Francois Furstenberg, Lori Glover, Annette Gordon-Reed, Nancy Isenberg, James E.McWilliams, Robin Mitchell, Rebecca Plant, Elizabeth Reis, Lisa Sigel, Roshanna Sylvester, David Waldstreicher, and-for making a trip to Mt. Vernon so enjoyable-Wayne Wheeler. I am also grateful to Jordan Stein, who provided timely, insightful, and encouraging words at a very critical point.

I thank Dr. Gerard Gawalt, in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, who granted me access to Gouverneur Morris's original diaries. Numerous other individuals helped me understand Morris's world, including Dena Goodman, Catherine Kudlick, Jeffery Merrick, Melanie Miller, and Ben Mutschler.

I am grateful to Marello Harris for his initial research at the University of Georgia; to Ramiro Hernandez and Katarzyna Szymanska for their help with various projects; and to DePaul University's College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences Undergraduate Research Assistant program for supporting the labor of Sandra Sasal, Zachary Stafford, and Katie Suleta. DePaul University has provided me with not only a reliable livelihood but also supportive colleagues and engaging students. I received additional financial support from DePaul in the form of a DePaul Summer Research Grant, a fellowship at the DePaul Humanities Center, a Competitive Research Grant, and travel funding.

As the book took shape, it benefited from the feedback and support of a small army of editors, peer reviewers, and even potential agents-but especially Debbie Gershenowitz, Gayatri Patnaik, and Janet Francedese and the team at Temple University Press.

Over the years, I honed my arguments and gained new understanding from the responses of audiences at the Gerber-Hart Library, the University of Northern Iowa, Purdue University at Calumet, and the University of Mary Washington. I was also fortunate to have the opportunity to discuss the work at a number of conferences, including the American Men's Studies Association Annual Conference, Creating the Past: Early American Museums between History and Edu-entertainment, the European Early American Studies Association Biennial Conference, the Newberry Seminar on Women and Gender, Queering Paradigms IV, and (Re)Figuring Sex: Somatechnical (Re)Visions.

Finally, I express my gratitude to New York University Press, Disability Studies Quarterly, the Journal of the History of Sexuality, and the corresponding anonymous peer reviewers, who provided useful feedback on portions of this project that I developed into essays published in these academic journals and in an edited volume published by New York University Press.

Sex and the American Quest for a Relatable Past

IVING AS WE DO in an era in which public figures are subjected to extreme scrutiny in the form of media intrusions, we tend to think of our interest in reconciling public images with private sexual conduct as uniquely postmodern. In fact, Americans have long invested national heroes with superior moral status and at the same time probed into their private lives. If the Founding Fathers seem remote to us now, that distance persists despite the efforts of generations of biographers who attempt to take their measure as leaders and tell us what they were really like in their most intimate relationships. From the early years of the Republic till now, biographers have attempted to burnish the Founders' images and satisfy public curiosity about their lives beyond public view. At the same time, gossips and politically motivated detractors, claiming to have the inside track on new information, have circulated scandalous or unpleasant stories to knock these exalted men off their pedestals. Looking back at the stories and assessments that have proliferated in the two and a half centuries since the Founders' generation, we see the dual nature of these accounts and how they oscillate between the public and the private, between the idealized image and actions in the intimate realm. We see how each generation reshapes images of the Founders to fit that storyteller's era.

IVING AS WE DO in an era in which public figures are subjected to extreme scrutiny in the form of media intrusions, we tend to think of our interest in reconciling public images with private sexual conduct as uniquely postmodern. In fact, Americans have long invested national heroes with superior moral status and at the same time probed into their private lives. If the Founding Fathers seem remote to us now, that distance persists despite the efforts of generations of biographers who attempt to take their measure as leaders and tell us what they were really like in their most intimate relationships. From the early years of the Republic till now, biographers have attempted to burnish the Founders' images and satisfy public curiosity about their lives beyond public view. At the same time, gossips and politically motivated detractors, claiming to have the inside track on new information, have circulated scandalous or unpleasant stories to knock these exalted men off their pedestals. Looking back at the stories and assessments that have proliferated in the two and a half centuries since the Founders' generation, we see the dual nature of these accounts and how they oscillate between the public and the private, between the idealized image and actions in the intimate realm. We see how each generation reshapes images of the Founders to fit that storyteller's era.

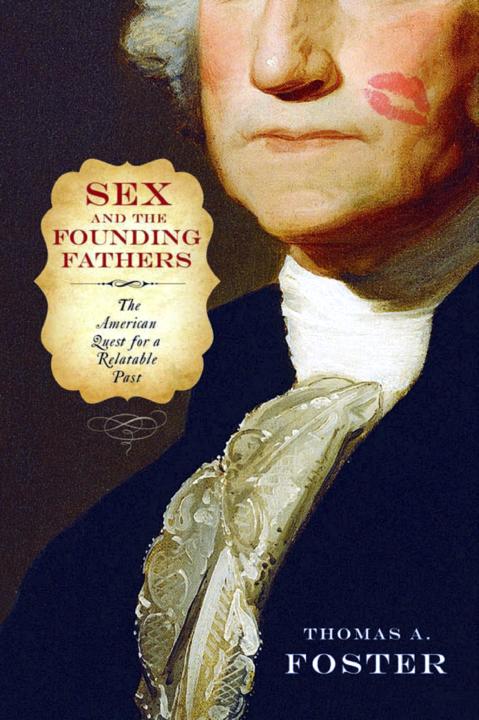

On the one hand, the Founders appear desexualized. The images of the Founding Fathers that we regularly encounter-as heads on money, as reference points in discussions about political ideology, and as monuments at tourist sites-assert their status as virtuous American men. They typically appear either disembodied-as heads or busts-or in clothing that reminds us of their political or military position. Their flesh is covered from neck to wrists, with only hands and face exposed. Typically, the men are frozen in advanced age-generally gray-haired, if not topped off with wigs-further confirming their identities as desexualized elder statesman for generations of Americans who associate sexual activity with youth.'

LTHOUGH MY NAME ALONE appears on the cover of this book, I could never have written this volume without the time and effort that were contributed by a humblingly large number of people. What follows is my acknowledgment of a mere portion of the help I received. The earliest idea for the book came from conversations with John D'Emilio, to whom I am most grateful for his mentoring and encouragement. The support and guidance of Mary Beth Norton have sustained me throughout not only this project but also my career.

LTHOUGH MY NAME ALONE appears on the cover of this book, I could never have written this volume without the time and effort that were contributed by a humblingly large number of people. What follows is my acknowledgment of a mere portion of the help I received. The earliest idea for the book came from conversations with John D'Emilio, to whom I am most grateful for his mentoring and encouragement. The support and guidance of Mary Beth Norton have sustained me throughout not only this project but also my career. IVING AS WE DO in an era in which public figures are subjected to extreme scrutiny in the form of media intrusions, we tend to think of our interest in reconciling public images with private sexual conduct as uniquely postmodern. In fact, Americans have long invested national heroes with superior moral status and at the same time probed into their private lives. If the Founding Fathers seem remote to us now, that distance persists despite the efforts of generations of biographers who attempt to take their measure as leaders and tell us what they were really like in their most intimate relationships. From the early years of the Republic till now, biographers have attempted to burnish the Founders' images and satisfy public curiosity about their lives beyond public view. At the same time, gossips and politically motivated detractors, claiming to have the inside track on new information, have circulated scandalous or unpleasant stories to knock these exalted men off their pedestals. Looking back at the stories and assessments that have proliferated in the two and a half centuries since the Founders' generation, we see the dual nature of these accounts and how they oscillate between the public and the private, between the idealized image and actions in the intimate realm. We see how each generation reshapes images of the Founders to fit that storyteller's era.

IVING AS WE DO in an era in which public figures are subjected to extreme scrutiny in the form of media intrusions, we tend to think of our interest in reconciling public images with private sexual conduct as uniquely postmodern. In fact, Americans have long invested national heroes with superior moral status and at the same time probed into their private lives. If the Founding Fathers seem remote to us now, that distance persists despite the efforts of generations of biographers who attempt to take their measure as leaders and tell us what they were really like in their most intimate relationships. From the early years of the Republic till now, biographers have attempted to burnish the Founders' images and satisfy public curiosity about their lives beyond public view. At the same time, gossips and politically motivated detractors, claiming to have the inside track on new information, have circulated scandalous or unpleasant stories to knock these exalted men off their pedestals. Looking back at the stories and assessments that have proliferated in the two and a half centuries since the Founders' generation, we see the dual nature of these accounts and how they oscillate between the public and the private, between the idealized image and actions in the intimate realm. We see how each generation reshapes images of the Founders to fit that storyteller's era.