OTHER BOOKS BY

WILLIAM J. COOPER

__________

We Have the War Upon Us:

The Onset of the Civil War,

November 1860April 1861

Jefferson Davis and

the Civil War Era

Jefferson Davis, American

Liberty and Slavery:

Southern Politics to 1860

The South and the Politics

of Slavery, 18281856

The Conservative Regime:

South Carolina, 18771890

The American South:

A History (coauthor)

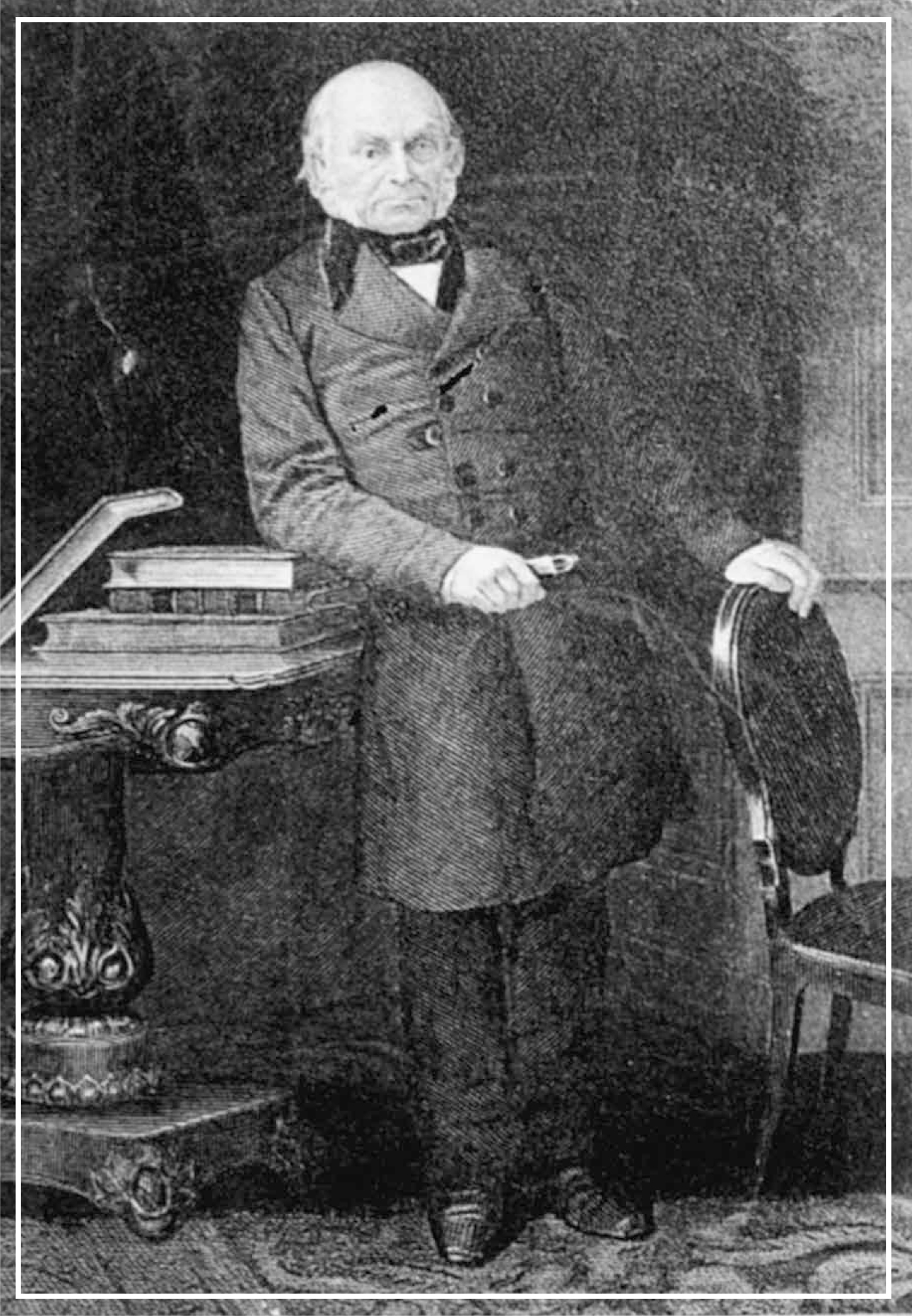

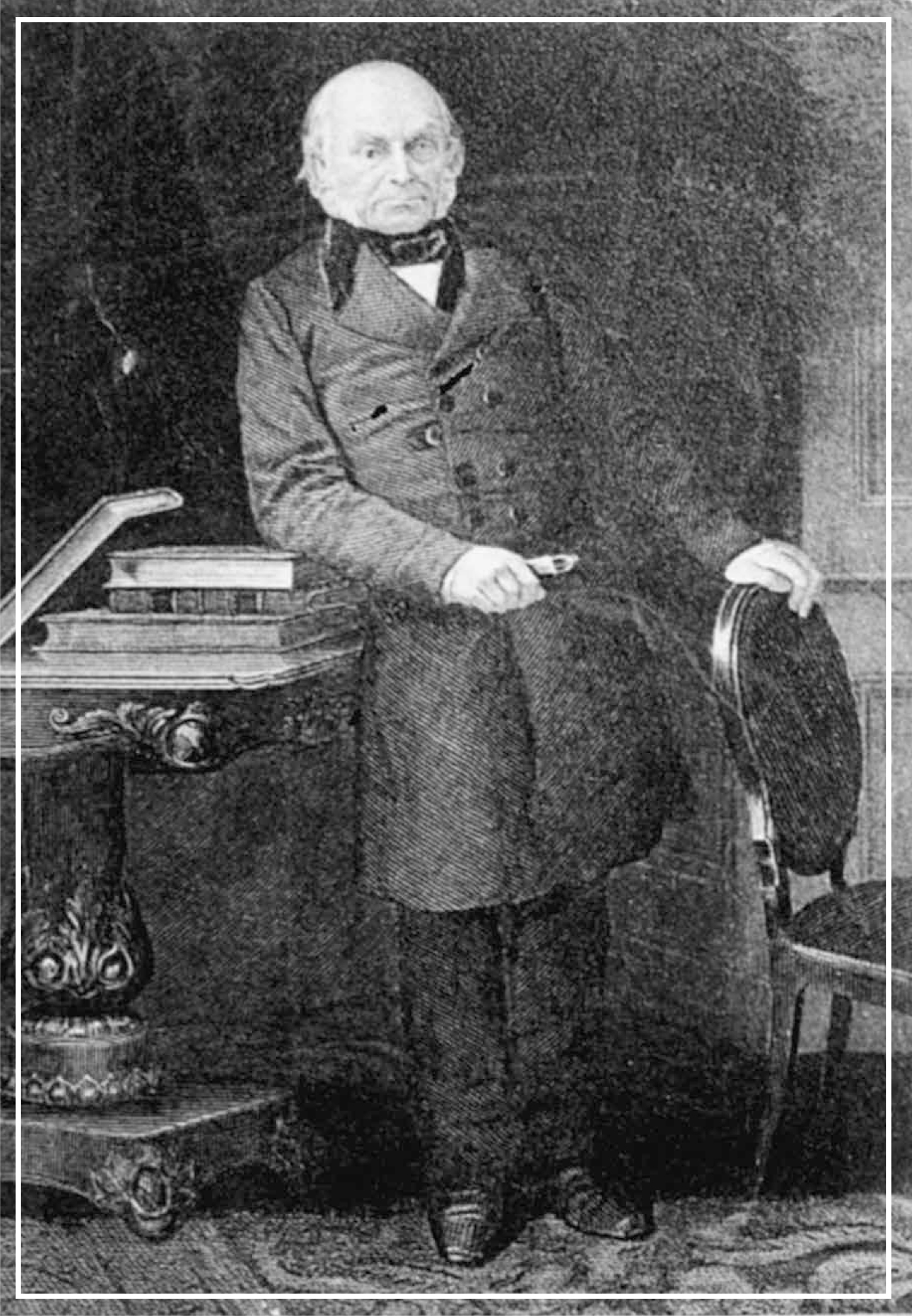

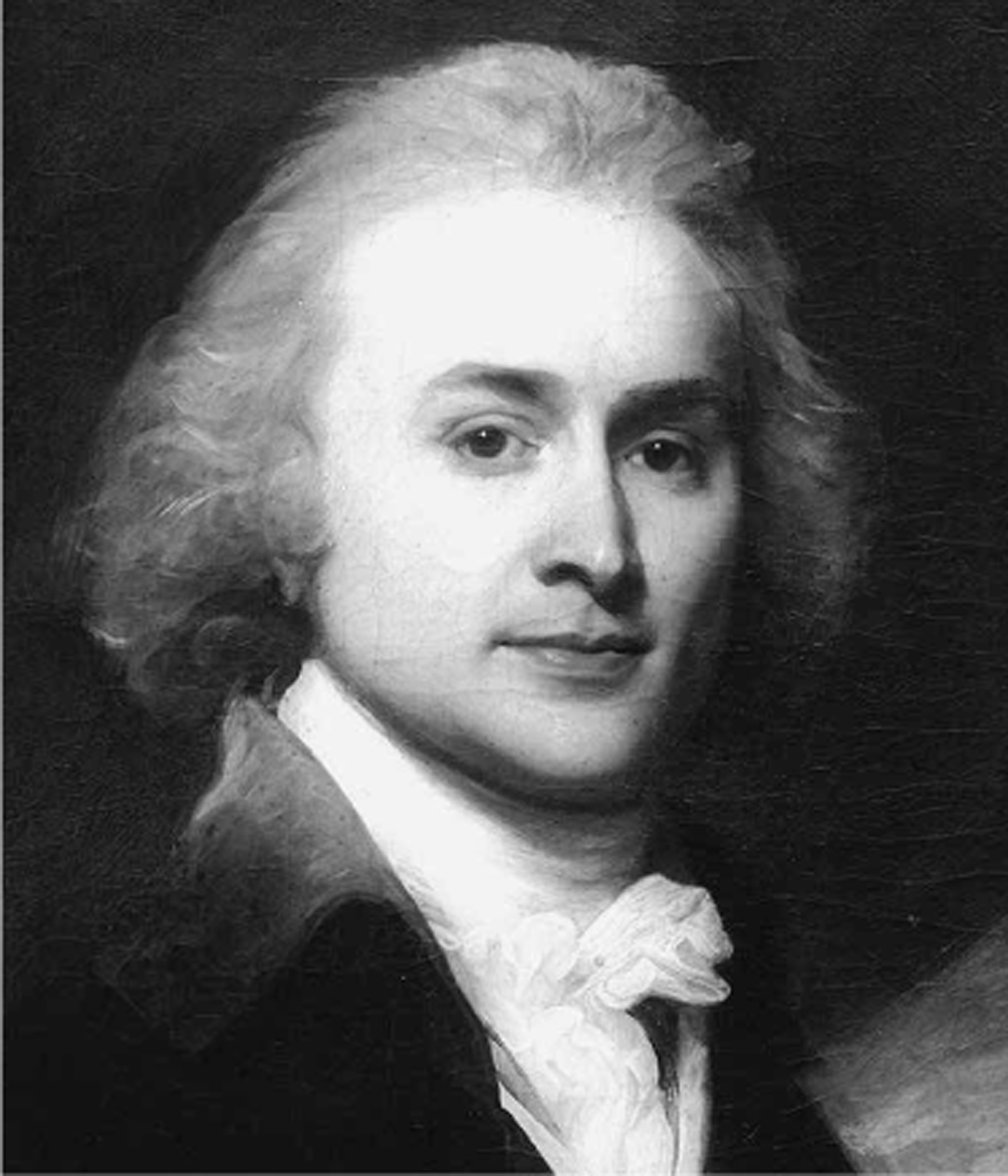

JOHN QUiNCY ADAMS (CA. EiGHTY)ENGRAViNG BY UNKNOWN ARTiST

Copyright 2017 by William J. Cooper

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Barbara Bachman

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

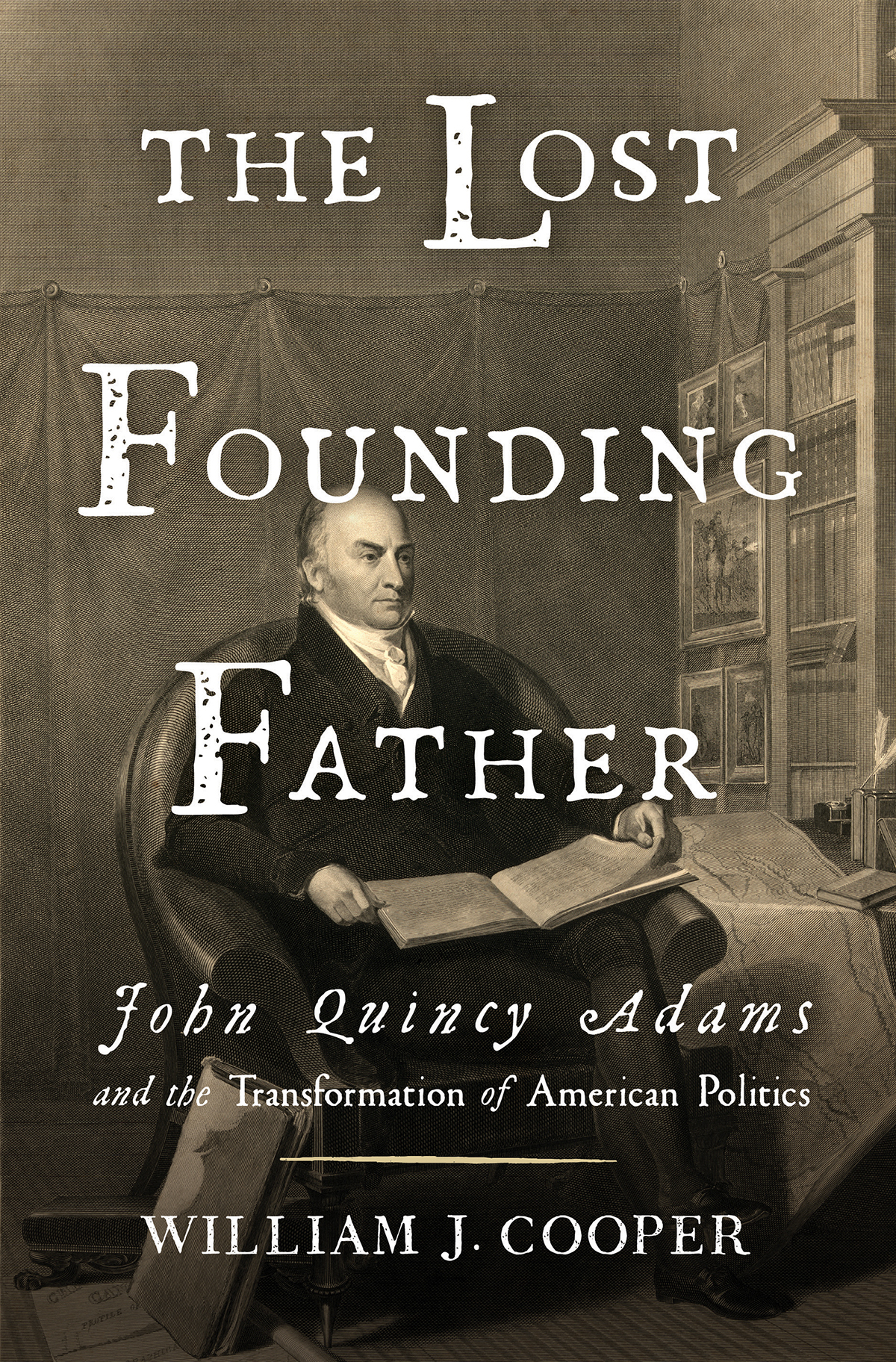

JACKET DESIGN: JONATHAN SAINSBURY // 6X9DESIGN

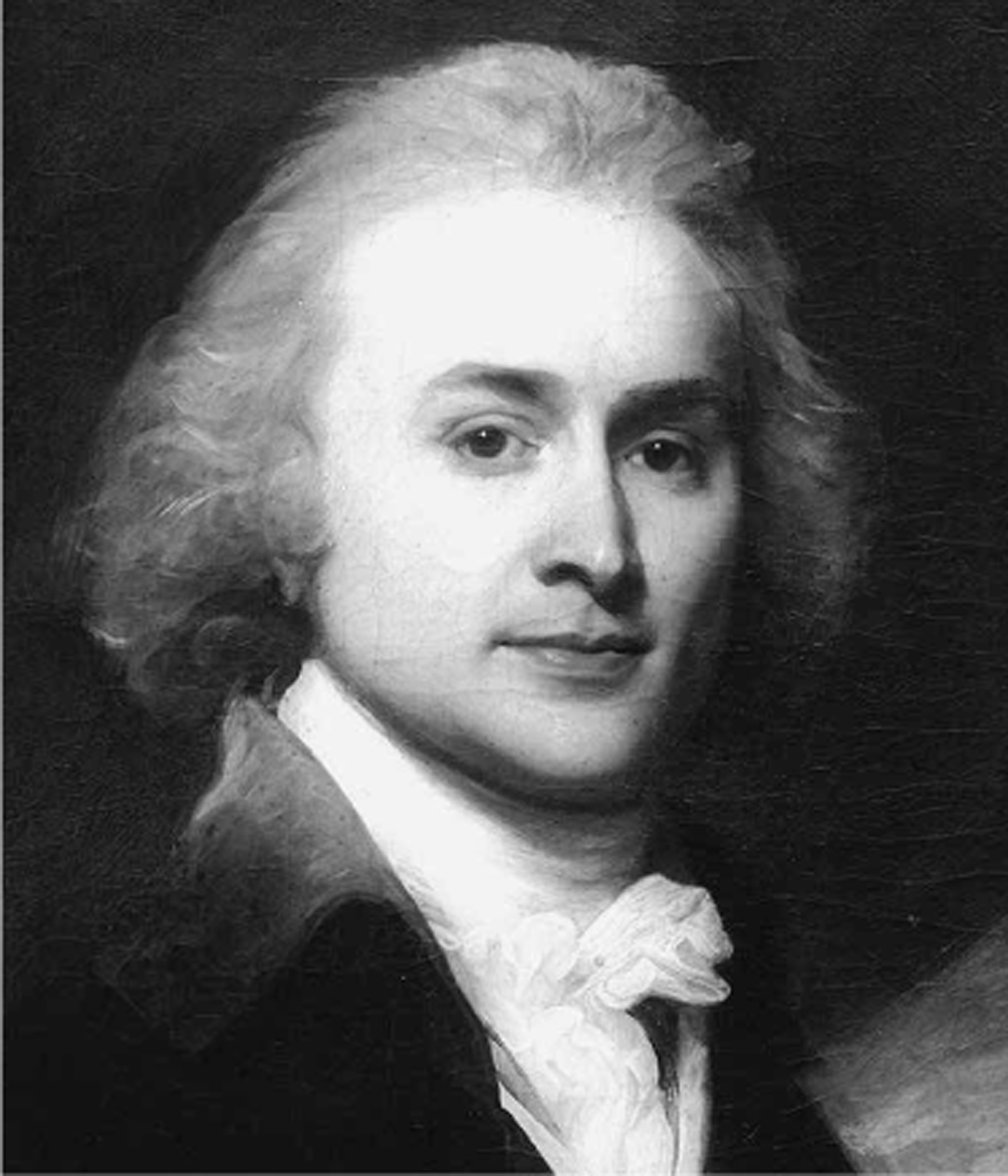

JACKET ENGRAVING: A.B. DURAND (SOURCE PAINTING BY T. SULLY), 1826. COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Cooper, William J., Jr. (William James), 1940 author.

Title: The lost founding father : John Quincy Adams and the transformation of American politics / William J. Cooper.

Other titles: John Quincy Adams and the transformation of American politics

Description: First edition. | NEW YORK : LIVERIGHT PUBLISHING CORPORATION, a division of W. W. NORTON & COMPANY, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017036932 | ISBN 9780871404350 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Adams, John Quincy, 17671848. | Founding Fathers of the United StatesBiography. | StatesmenUnited StatesBiography. | United States. ConstitutionSignersBiography. | United StatesHistoryRevolution, 17751783. | United StatesPolitics and government17831789. | PresidentsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC E377.C675 2017 | DDC 973.5/5092[B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036932

ISBN 978-1-63149-389-8 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Patricia

CONTENTS

J OHN QUINCY ADAMS OCCUPIES A CAMOUFLAGED POSITION in U.S. history. With his public career lodged between the grandeur of the American Revolution and the drama of the Civil War, he has been overshadowed. Son of a major Founding Father, John Adams, the second president, John Quincy knew personally the giants of the founding generation, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and James Monroe. And from the mid-1790s to the mid-1820s, he held important diplomatic posts, culminating in his service as secretary of state in Monroes cabinet. In that office he was the chief architect of a foreign policy that made his country a continental nation and asserted American preeminence in this hemisphere. Then in 1825 he became the sixth president of the United States. That path alone should have secured him a prominent place in the national pantheon.

Yet, that elevation did not take place. Just as John Quincy entered the presidency, a mighty upheaval began to revolutionize American politics. A new, popular politics energized by sharply increasing numbers of voters along with the growth and maturation of political parties was supplanting an arena in which a restricted electorate coupled with personal loyalty predominated. The politics of our time really began at this momenta combination of parties directed by political professionals, vigorous, even raucous, campaigns, legions of voters demanding attention, and candidates striving to connect with those same voters.

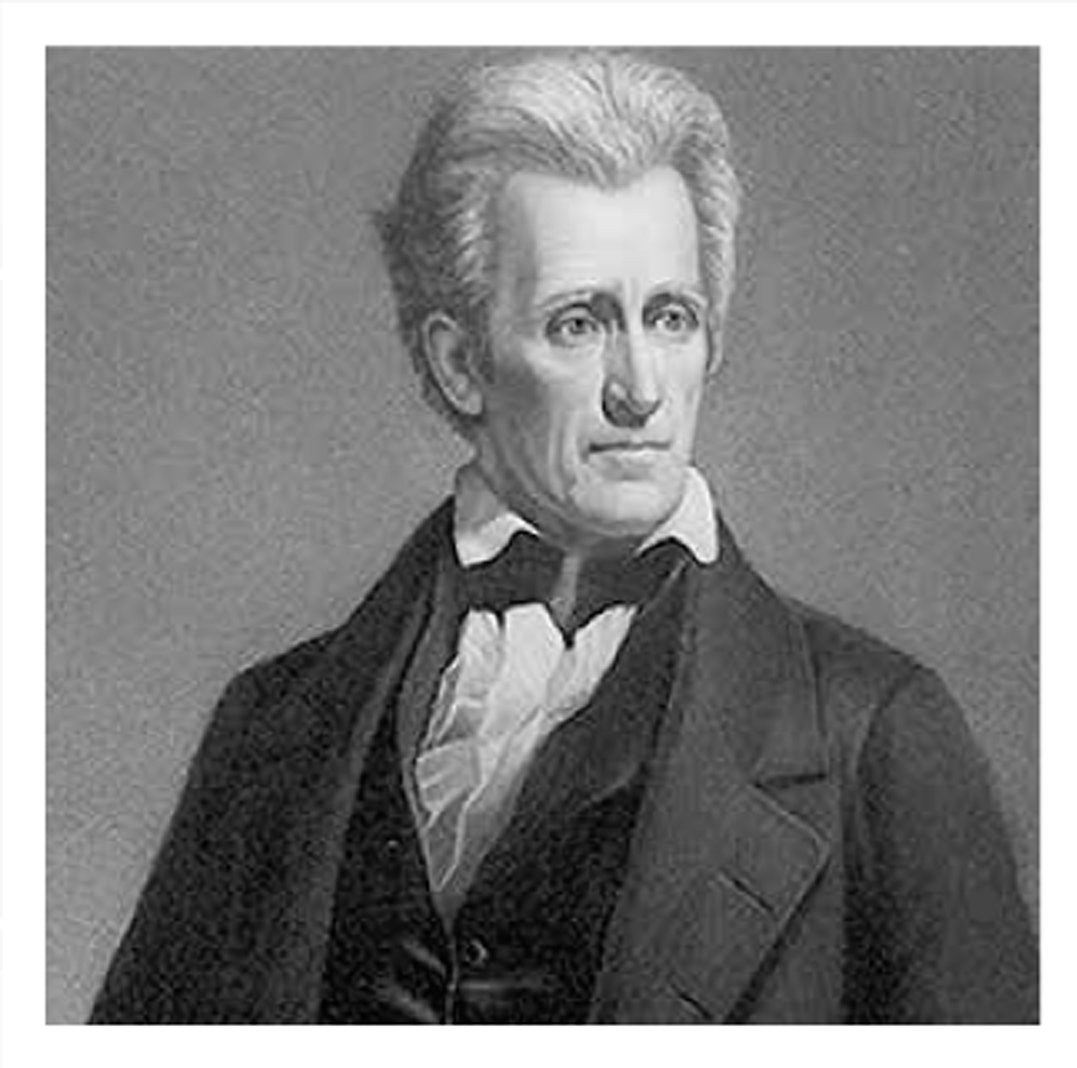

That momentous shift became identified with Andrew Jackson, who defeated John Quincy when he tried for reelection. A military hero of the War of 1812, Jackson was the first president from west of the Appalachian Mountains. He was also emphatically the first not intimately associated with the Founders. Furthermore, he and his partisans became equated with the broadening franchise that underlay what can legitimately be called the democratization of American politics for white men, the political universe at that time. In spite of Jacksons recent condemnation by some as a slave owner and warrior against Native Americans, no doubt can exist about the political transformation that accompanied his ascendancy. It fundamentally altered the political world. And in that world John Quincy never felt comfortable. He clung tenaciously to values and an outlook much closer to those of the Founders. He was the link to a political world that could not hold.

Driven from the presidency, as he saw it, an embittered John Quincy believed that he had been wronged by political pirates. He viewed himself as an artifact, as did many contemporaries. For years most historians agreed.

John Quincy declined to remain in isolation, however, a man politically dead communing with the physical dead. Refusing to conform with his presidential predecessors in their retirement from public life, he entered the national House of Representatives in 1831 and would abide there until his death seventeen years later.

John Quincy Adams began his congressional career as a vehement opponent of Jackson, whom he thought unfit for the presidency and leading the country in the wrong direction. John Quincy envisioned a dynamic central government dedicated to active involvement in economic and financial policy and to funding internal improvements (roads and canals), education, and science. But his dream became submerged under a cascade of voters fearing federal power.

Although John Quincy never surrendered his vision, while he served in Congress his concern with southern political power mounted. Both the policies it pursued and the evil institution of slavery it defended alarmed him. Secure in his House seat, John Quincy led the congressional fight against what he deemed to be an essentially un-American South. Successfully battling against southern opposition, he maintained the right of citizens to petition for what they wanted, especially antislavery measures. Even if he disagreed with certain of their requests or found them divisive, John Quincy still felt the Constitution guaranteed citizens the prerogative to make them. Yet, he failed to halt the westward advance of slavery and the onset of the war with Mexico, a clash he denounced as a proslavery gambit. In these efforts he came publicly to doubt whether the country could continue with both slave and free states. He stood as the first major public figure to reach that conclusion.

But his death in 1848 occurred a few years before the advent of the sectional Republican party, which was bent on halting the march of slavery and curbing its political impact. The success of the Republican cause and especially the rise of Abraham Lincoln with his twin triumphs over disunion and slavery dimmed John Quincys memory.

Next page