We hope you enjoyed this book.

Since 1944, Mercier Press has published books that have been critically important to Irish life and culture. Books that dealt with subjects that informed readers about Irish scholars, Irish writers, Irish history and Irelands rich heritage.

We believe in the importance of providing accessible histories and cultural books for all readers and all who are interested in Irish cultural life.

Our website is the best place to find out more information about Mercier, our books, authors, news and the best deals on a wide variety of books. Mercier tracks the best prices for our books online and we seek to offer the best value to our customers, offering free delivery within Ireland.

Sign up on our website to receive updates and special offers.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

twitter.com/IrishPublisher

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Introduction

GERRY ADAMS

Sinn Fin President

I find it startling to hear myself say that I am prepared to die first rather than succumb to their oppressive torture and I know that I am not on my own, that many of my comrades hold the same.

Such prophetic words from Bobby Sands two years before his death, written at a time when the blanket men in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh and the women POWs in Armagh Jail had already been on protest for three years. That protest, prison confrontation, and, ultimately, hunger strike, only came about because the British government consciously decided to make the prisons a battleground, to try and defeat in prison those who it couldnt defeat in the field of armed struggle.

Up until 1969 the prison population in the north of Ireland was small and could be counted in a few hundred. But that was soon to change, both in numbers and composition, as a result of the repressive reaction of the unionist government to the peaceful Civil Rights Movements demands for reform in local government (including for many nationalists the right to vote), in housing and for an end to the Special Powers Act.

After the British Army was reintroduced in the six counties in August 1969 it soon became clear from its actions that it was here as an instrument of unionist and British misrule. Those actions included attacking nationalists, firing gas indiscriminately, and curfewing and raiding nationalist areas for weapons which had never been used for offensive purposes but solely for defence. The IRA, in turn, re-emerged and reorganised and fought back against the British Army and the northern state.

After 1969 the prison population exploded as protesters, young nationalist demonstrators and Irish republican activists were arrested and charged with various offences, convicted and sentenced to time in prison; or were arrested without charge and interned without trial in various prisons, including Long Kesh Prison Camp.

In 1972 veteran republican Billy McKee, a sentenced prisoner in Crumlin Road Jail, led a hunger strike demanding political status. Before there were any deaths, the British government acceded to the prisoners demands and granted special category status, a face-saving expedient for what was, in reality, political status. Under this regime prisoners organised their own lives within the prison, wore their own clothes, carried out their own education and were organised within their own command structure.

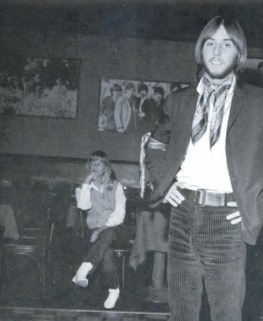

Bobby Sands had been one of those young people whose family suffered sectarian harassment and who were driven from their home in Rathcoole, North Belfast, moving to the Twinbrook estate on the outskirts of West Belfast. In October 1972 Bobby was arrested and charged with possession of four handguns. While on remand he got married and in April 1973 was sentenced to five years in jail, which is where I first met him. I had been interned in June 1973 but was charged with attempting to escape and was sentenced to two terms of imprisonment. When internment ended in 1975, I was moved from the internees cages to Cage 11, where Bobby was serving his time.

Roimhe seo, bh Ribeard i gCs 17 agus seo mar a bhfuair s an gr a bh aige don Ghaeilge. Ddh Campa na Ceis Fada i m Dheireadh Fmhair 1974 agus ina dhiaidh seo chrochnaigh s suas sa bhothn Gaeltachta i gCs 11. Bh an-tsuim aige sa teanga, le sean-Phroinsias Mac Airt go ndeana Dia trcaire ar a ainm agus Coireall Mac Curtin Luimneach mar mhinteoir aige. Bhain s ard chaighdan amach measartha gasta agus fuair s Finne ir roimh deireadh 1975.

Bas an Tr Ghearr cuid mhr d chairde ach bh Bobby balta meascadh go furasta le gach duine sa chs. Bh s go maith ar an ghiotr agus bh ceol aige agus bh s lidir agus dograsach mar pheileadir i lr na pairce. Chuir muid aithne ar a chile le linn na ndospireachta agus na tgra oideachais a bh idir limhe againn i gCs 11. Chomh maith leis sin bhain an bheirt againn said as an bhothn staidara go mion minic, bh mise ag dul don scrobhnireacht agus bh seisean ag cleachtadh ar an ghiotr, n ag teagasc agus ag foghlaim na Gaeilge san it ciin suaimhneach sin, ar shil n ruaille buaille agus tormn sna gnth bothsin.

Before this, Bobby was in Cage 17 and it was here that he developed a strong love for the Irish language. In October 1974, after the burning of the camp, Bobby was moved to Cage 11 and moved into the Gaeltacht hut. He was an avid Gaelgeoir, and was taught by the late Proinsias MacAirt and then by Coireall Mac Curtain from Limerick. He became fluent and attained gold finne level within a short space of time.

Bobbys close associates were Short Strand men, but he mixed easily with everyone in the cage. He was a decent singer and guitarist and a robust and enthusiastic soccer footballer. He and I got to know each other better through the political discussions and educational projects which were organised in Cage 11. The two of us also used the study hut a lot me for writing, he for practising his guitar or for studying Irish as it was possible to get quiet time there, away from the hustle, bustle and noise of the huts.

I have often said that Bobby Sands was a very ordinary person. He would not stand out in a crowd nor push himself forward. Yet, like some special ordinary people who find themselves in extraordinary circumstances Bobby was to go on to do extraordinary things. I remember him as an earnest yet good-humoured and good-natured young man; an obviously committed republican with a willingness to learn, to educate and to be part of building our struggle to achieve its objectives. He used his time in prison so that on his release he would be able to make a greater and more meaningful contribution to the struggle. I remember well the time, those weeks, just before Bobbys release in 1976, about ten months before I myself got out. We use to boowl (dander) round the exercise yard together, discussing the struggle, its history, the situation on the outside, the lay of the land, the state of things, with Bobby quizzing me about my own views. Though we were to write to each other throughout the first hunger strike and for some time into his own hunger strike, the next time I was to see Bobby was in his coffin in the living room of his parents home in Twinbrook, five years later.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press