Table of Contents

I have the bad and disagreeable habit of writing the truth as I see it.

IRA leader Ernie OMalley in a letter to republican activist Sheila Humphreys, 1938

Bik McFarlane: Well, Rick?

Richard ORawe: I think theres enough there, Bikso.

Bik McFarlane: I agree. Ill write to the outside an let them know our thinkin.

H-Block 3, 5 July 1981

Reporter: Who took the decision to reject that [Mountain Climber] offer?

Bik McFarlane: There was no offer of that description.

Reporter: At all?

Bik McFarlane: Whatsoever. No offer existed.

UTV News, 28 February 2005

That conversation did not happen. I did not write out to the [ IRA ] Army Council and tell them we were accepting [a deal]. I couldnt have. I couldnt have accepted something that didnt exist.

Bik McFarlane, Irish News, 11 March 2005

Something was going down. And I said to Richard [ORawe], this is amazing, this is a huge opportunity and I feel theres the potential here [in the Mountain Climber process] to end this.

Bik McFarlane, Belfast Telegraph , 4 June 2009

I confirm what Richard said all along. He is 100 per cent correct. Ive no doubts that hes right in what he says.

Gerard Cleaky Clarke, 23 May 2009

I think, morally, that the leadership on the outside should have intervened [to end the hunger strike]. This is an army; we were all volunteers in this army; the leadership had direct responsibility over these men. And I think they betrayed to a large extent the comradeship that was there

[It was] cowardly in many ways to allow mothers and sisters and fathers to make these decisions [to allow or not to allow their loved ones to die] allowing that to happen was a total disregard of the responsibility that they had to these people

I believe that was the reason why the leadership on the outside did not intervene, because of the street protests that were taking place, because of the political party that Sinn Fin was building.

Brendan The Dark Hughes

from Ed Moloney, Voices from the Grave (2010)

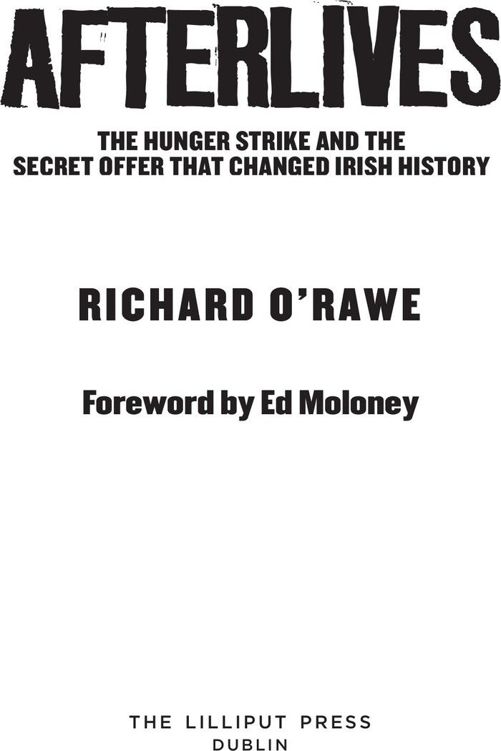

Foreword

THIS IS quite possibly one of the most important stories to come out of the Troubles in Northern Ireland because it helps to explain how and why they came to an end in a way that is revelatory, deeply disturbing, unprecedented and convincing. But before I explain what I mean by all that, I have a confession to make. As they say in the country where I now live, I have, or rather had, a dog in this fight. I did not want Richard ORawe to go down the road that has led to this book.

It was not that I did not want the story of what really happened in the H-Blocks of Long Kesh during the torrid summer of 1981 to be told. Far from it. I am a journalist very much of the publish and be damned school, a firm believer that if you know a story to be true and important and that its publication will not result in physical harm to others, then you should do all you can to get it out to the reading, listening or viewing public. Why be a journalist otherwise?

I also believed Richards account from the moment I heard it. During much of the hunger strike period in 1981, I was the stand-in Northern Editor of The Irish Times and I am pleased to say that the work of the papers Belfast office during those awful months was in a league of its own. We broke one story after another and got closer to what was going on than any other media outlet.

As a result of what I had learned, I had become extremely sceptical of the official line from the Provos that the prisoners were in charge of the protest. The small bits and pieces of evidence that I had accumulated suggested that Gerry Adams and the people around him were really calling the shots and, by August 1981, I had come to believe that they were not interested in a settlement. It wasnt just that the procession of coffins from the prison hospital in Long Kesh was helping to keep the pot boiling on the streets of Northern Ireland, which it was, but that I had a fair idea of what was really going on in the minds of the Provo leadership.

Long before the hunger strikes happened, I knew that there was a strong view in the group around Gerry Adams (we didnt call it the Think Tank in those days but that is what it was) that Sinn Fin should go political, and stand for elections. But that was a dangerous argument to advocate in a movement that had split from the Official IRA largely in protest at the contaminating effect of conventional politics. The Provisionals were people for whom the gun was the purest and only acceptable expression of political belief, whereas electoral politics, as Irish history bore witness, was the pathway to reformism and compromise.

By 1979 or 1980, those around Adams would talk wistfully to me of how, in five or ten years maybe, they might be able to persuade their other colleagues to stand Sinn Fin candidates for Belfast City Council. But that was as far as their horizons were permitted to expand. Suddenly, just a couple of years later, all had changed utterly. Bobby Sands had been elected to Westminster and Kieran Doherty and Paddy Agnew returned to the Dil. All three were IRA prisoners. Council elections in the North had in the meantime seen success for anti-H-Block candidates, especially in Belfast, and Owen Carron was poised to take Sands seat after his death had created a by-election.

It seemed to me that fate had dealt an extraordinary hand to the Adams camp. Suddenly they had an opportunity to fast-forward all their political ambitions in a very real way. Gone was the limited goal of winning seats to Belfast Council in the distant, uncertain future; now it was possible to get into the big game in one go and to do so in a very acceptable way to their grassroots. The dismay and even anger shown by the British and Irish establishments, along with the bulk of the media, at the electoral success of the hunger strikers had, in the eyes of IRA supporters, transformed the mundane process of seeking votes into a worthwhile revolutionary tactic.

So when Richard ORawe came forward with a story that strongly suggested that efforts to reach a settlement of the hunger strike in July 1981 had been thwarted by Gerry Adams and those around him, it made complete sense to me. A settlement in July would probably have cost Owen Carron the Fermanagh-South Tyrone by-election and torpedoed Sinn Fins ambitions to embrace electoral politics.

The key bloc in that constituency, SDLP supporters who normally reviled the IRA, had got Sands elected in order to end the hunger strike but if the protest had ended before the next by-election why on earth would they come out to vote for Carron? Keeping the hunger strike going gave them a reason to vote for Carron and hence the motive for undermining a proposed resolution. Victory in the Fermanagh-South Tyrone by-election made it easier for Sinn Fin leaders to persuade their followers to embrace electoral politics.

I had long suspected that something like this had happened and wrote words to that effect in my study of the peace process, A Secret History of the IRA . But I had always focused on events at the end of July when Gerry Adams and Owen Carron had visited the H-Blocks to talk to the hunger strikers but stopped well short of ordering them off the protest as Adams had told Fr Denis Faul he would. What I did not realize, until Richard ORawe told his story, was that the key moment had come earlier that month.

There was another reason why I believed his story. By 2001 I had left Ireland and was living in New York. But before I departed, I had set up an oral history archive funded by Boston College designed to collect the life stories of those who had fought in the conflict. These were stories that would be lost otherwise and which could now be safely collected, given that the Troubles were ending. The stories would stay in the archive until the interviewees death, after which they would be made public; at least that was the plan.