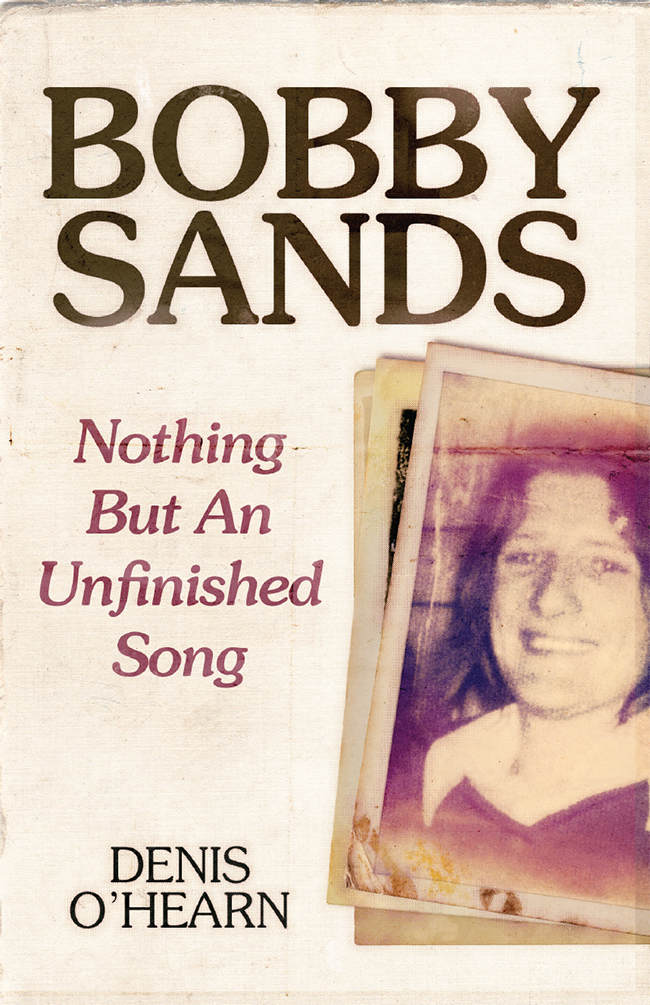

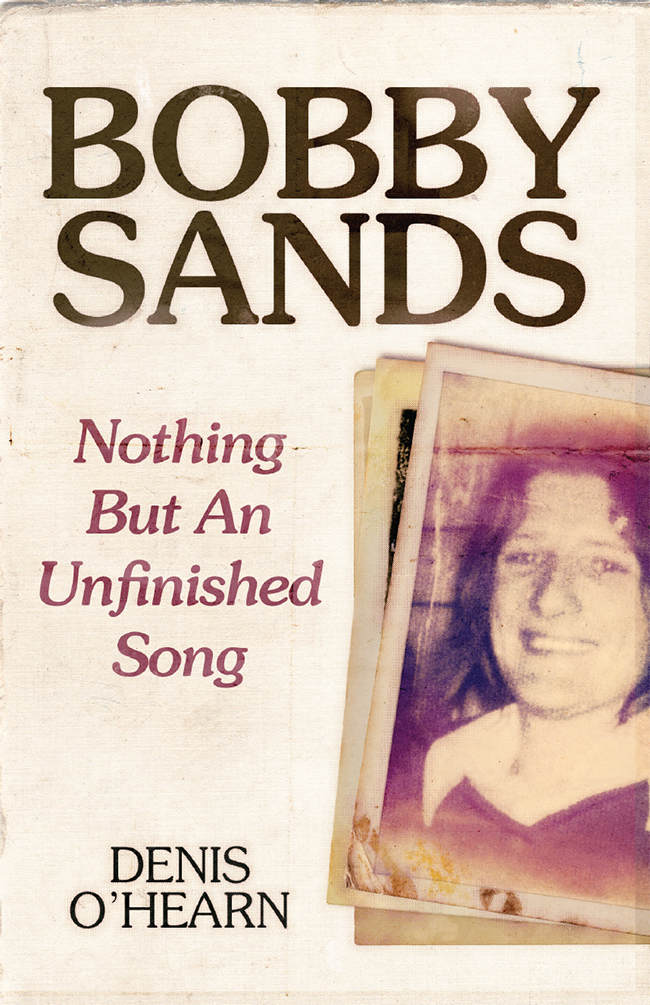

Bobby Sands

Bobby Sands

Nothing But an Unfinished Song

New Edition

Denis OHearn

First published 2006

New edition published 2016 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright Denis OHearn 2006, 2016

The right of Denis OHearn to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3633 6 Paperback ISBN 978 1 7837 1809 2 PDF eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1811 5 Kindle eBook ISBN 978 1 7837 1810 8 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Printed in the European Union

Contents

For those who die too young.

For my nephew, James Padraic OHearn.

May your heart always be joyful,

May your song always be sung.

In the twilight of my last morning I will see my friends and you, and Ill go to my grave regretting nothing but an unfinished song ... Nazim Hikmet,

Bursa Prison, Turkey, 11 November 1933

Foreword Culture Flies through Walls

by Mumia Abu-Jamal

It is delightful to learn that the saga of Bobby Sands is still being read in dungeons and solitary prison cells around the world. From Ohios death row to Californias supermax cells, Bobbys tale of struggle and resistance on behalf of Irish independence resonates. From Long Kesh to Pelican Bayfrom hole to hole.

This is a bright shimmering example of how culture, especially the culture of resistance, can seep, like water, through brick and steel, across oceans and through the false barriers imposed by the illusions men have erected and called race.

My memory of Sands listening to soulful Motown stars like Diana Ross and Freda Payne was only exceeded by the surprise that, as a youth, his favorite movie was Zulu , an epic tale of the Zulus attack on and destruction of the British imperial army at Isandlwana (and British revenge at Rorkes Drift). This told me all I needed to know.

Denis OHearn, in his now classic Bobby Sands: Nothing But an Unfinished Song , recounts the seething rage of Irish youngsters watching (and often experiencing!) British army foot patrols harassing guys in the streets of Belfast. Jimmy Rafferty, a friend of Sands, comes to him frothing with anger:

Did you get seeing Zulu last night? [Bobby] asked Rafferty, referring to the classic film starring Stanley Baker, Michael Caine and a raft of unknown African actors and extras.Aye, I did, replied Rafferty.But he didnt want to talk about the film; he wanted to vent his anger about being spread-eagled against the wall.Im wrecked, Sandsy, he told Bobby. These here Brits had me up against the wall for over an hour. One of these days Im going to get laid into them bastards.Bobby just gave him a disdainful look and referred back to [his favorite scene in] the previous nights movie where the British army, out of ammunition, was wiped out by the Zulus in hand-to-hand combat.Look, Raff, are you gonna be Stanley Baker or are you gonna carry a spear?!

With these words we see a young man who was giving voice to his internationalist and anti-imperialist instincts.

In the prisons of the occupier (Britain), Sands and his IRA comrades used everythingand nothing!to resist the forces of repression and foreign occupation.

Nothing? Their hunger strikes in H-Block segregation in Long Kesh prisonhunger until deathgives nothing a new meaning, as does their struggle for human dignity.

That action has morphed into legend and has inspired men and women from Long Kesh to Californias infamous Pelican Bay, to Ohios death row non-contact visiting rooms, to supermax joints in Turkey, and beyond.

When prisoners went on hunger strikes in Pelican Bays SHU (Security Housing Unit) in 2011 and 2013, the leaders were a multi-racial bunch who had read of Sands in Nothing But an Unfinished Song and were inspired by the lads in Long Kesh. Their strikes, which drew an astonishing 30,000 strikers all across the California prison archipelago, had its inspiration in the H-Block struggle of Sands and his comrades.

Similarly, the men in Ohios death row, veterans of the 1993 Lucasville prison uprising, were sparked by Bobby Sandss hunger strike against intolerable conditions. They struck, and demanded, among other things, contact visits with their familiesand WON!

One of these men (again a multiracial group) is named (or named himself, rather) Bomani.

Sound familiar? Well, to be honest, theres no reason it should unless you, like Bobby, were a fan of the Zulu story of resistance to British imperialism.

In 1986 the South African Broadcasting Company produced a biopic of Zulu King Shaka. In the movie, featuring a glorious panorama of the tribe, when Shaka seizes the throne from his quavering half-brother he is assisted by Bomani, a powerful military figure.

Culture, especially the culture of resistance, is like the wind; a zephyr moving through brick and steel, through time itself, to touch other minds and souls.

It is usually outlawed, illegal, or deemed not acceptableor banned. Yet it continues to blow, moving here, moving there, until it refreshes another oppressed person with the human elixir of hope.

Then it moves on.

This book is like that.

May it continue to reach those it was conceived to reach; those who need a breath of fresh air, over the fetid stink of a sweltering segregation cell, or a barren, barred site called death row .

From the Prison-House of Nations (USA)

Mumia Abu-Jamal

Slow Death Row

Fall 2015

Authors note: This version of Bobby Sandss conversation with Jimmy Rafferty differs slightly from that presented in this book on p.28. As often happens in prison, Mumia Abu Jamal had an earlier draft of this book, which I edited after reviewing the movie Zulu . While the moral of each version of the conversation is different, they both demonstrate Bobbys budding anti-imperialist views.

Preface to the New Edition

I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all, to keep alive in our hearts a sense of the inexpressibly human. Richard Wright, Black Boy

When Pluto Books contacted me to say that they wanted to release a second edition of this book to mark the thirty-fifth anniversary of Bobby Sandss hunger strike, I was delighted. They said that they wanted to reach a whole new readership.

Indeed!

I am proud to say that this book continues to find new readers and, in some surprising ways, it has been a call to action for some remarkable people who found that the story of Bobby Sands and his comrades in Long Kesh prison back in the 1970s and 1980s provided the basis of a way forward in their own struggles.

This book has had a remarkable life. It never reached the bestseller list of the Sunday Times or the New York Times . Yet it hurled words into darkness, as Richard Wright put it, and it found echoes and awoke new wills to fight, new hunger for life.

Soon after this book was first published, the legendary civil rights activist Staughton Lynd organized a prison reading group that included some of the best minds in the United States prison system (Mumia Abu Jamal, Bomani Shakur, and others) and some of the most committed prison rights activists. This was their first text. Bomani, who is on death row in Ohio for his part in the 1993 Lucasville prison uprising, wrote to me after they read and discussed the book. I began visiting him in Ohio and over time we became brothers.

Next page