First published in Great Britain in 2009

Reprinted 2014

Reprinted 2015

2009 for the estate of Elma Napier

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset in Sabon

Design by Andy Dark

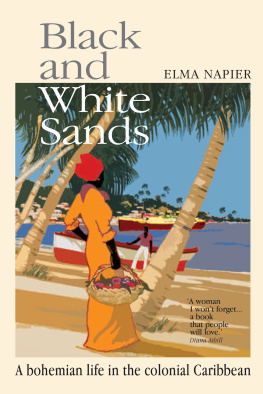

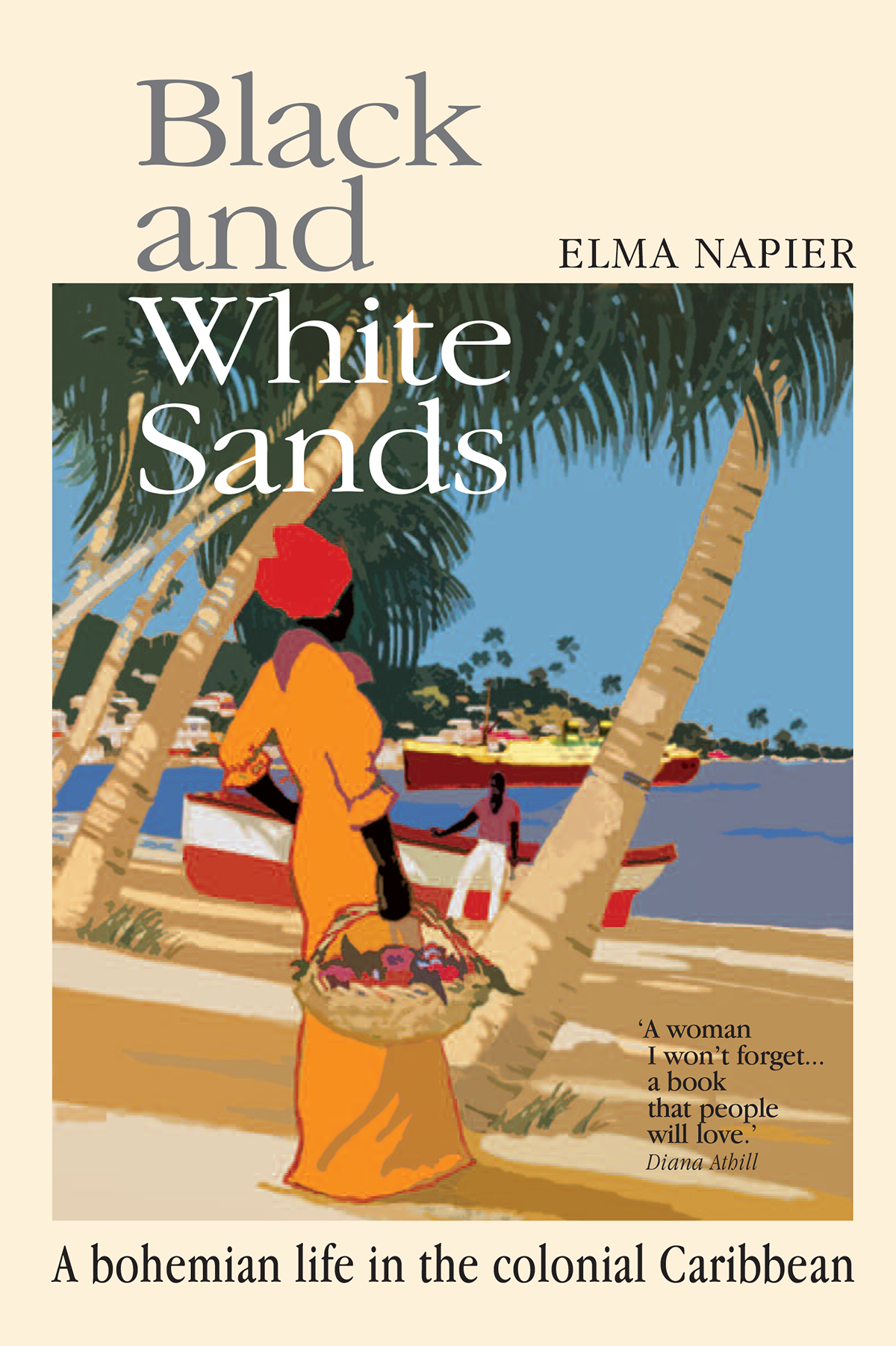

Cover design by Andy Dark, adapted from a vintage Royal Mail line poster

by Kenneth Shoesmith

ISBN: 978 0 9532224 4 5

Papillote Press

23 Rozel Road

London SW4 0EY

United Kingdom

www.papillotepress.co.uk

and Trafalgar, Dominica

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The publisher would like to thank the family of Elma Napier, in particular Patricia Honychurch and Lennox Honychurch for their permission to publish the book, and for their unstinting support, wealth of knowledge and generosity; also many thanks to Michael and Josette Napier for their help, in particular for the loan of photographs, and to Alan Napier likewise. Thanks, too, to Margaret Busby, for the index. All photographs, unless otherwise credited, are courtesy of the Honychurch and Napier families.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Nothing So Blue (1927)

Duet In Discord (1936)

A Flying Fish Whispered (1938, republished by Peepal Tree Press , 2009)

Youth Is A Blunder (1948)

Winter Is In July (1949)

Contents

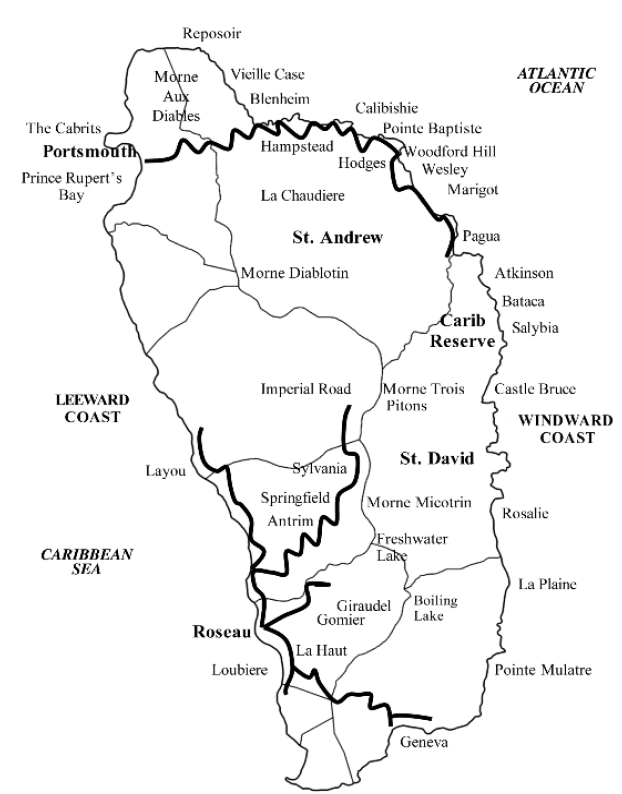

Dominica

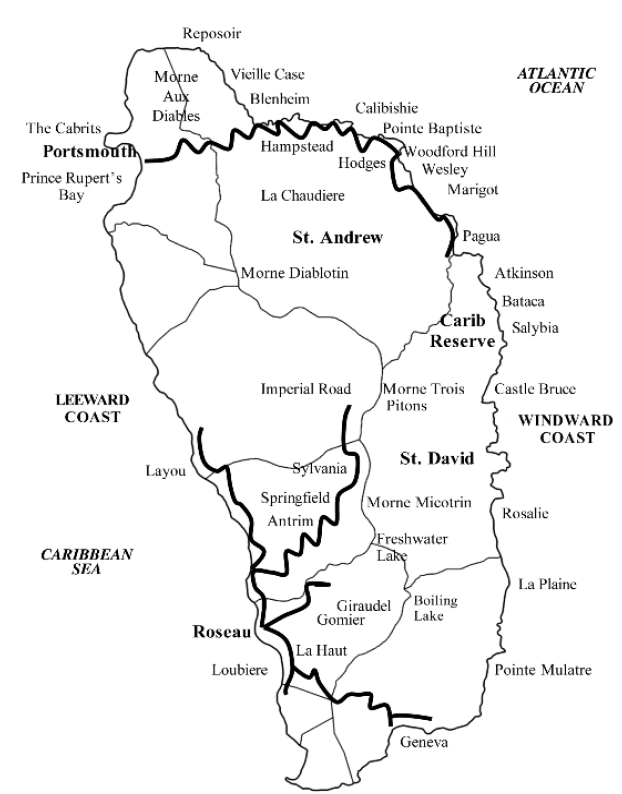

Map of Dominica showing the main places mentioned in this book, parish boundaries and the extent of motorable roads on the island before 1956. The parishes of St. Andrew and St. David made up the constituency of Lennox and Elma Napier in the Legislative Council.

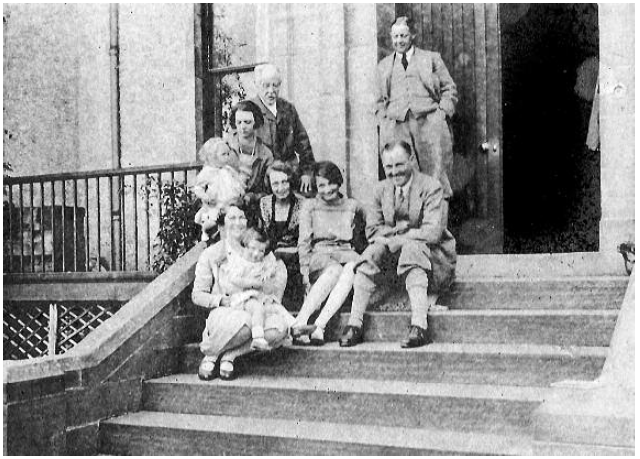

Elma Gordon Cumming as a child in Scotland in 1899.

I have made of my life a curious patchwork, wrote Elma Napier. Indeed, by the time she arrived in Dominica with her husband and children in 1932, this talented and fearless woman had spent her childhood on a grand estate in the Scottish highlands, lived in the Australian outback, visited the South Seas, and danced with the future Edward VIII. More significantly, she had emerged from two scandals: the social ostracism of her aristocratic father from the Edwardian court, and her own adultery and divorce. Such emotional upheavals she never mentions in Black and White Sands but they shaped her life, and, ultimately, brought her to the wild tropical shores of Dominica where she lived until her death in 1973 at the age of 81.

Elma Napier was born in Scotland, the eldest child of Sir William Gordon Cumming, whose family had owned half of Scotland, including the house that later became Gordonstoun school. But in 1890, two years before her birth, Sir William was accused of cheating during a baccarat game with the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII). This famously became known as the Tranby Croft affair. Sir William sued for defamation, and lost. He also lost his place in high society, and was, for ever after, shunned. No one spoke to him, wrote his daughter of her fathers disgrace.

But Elma was to suffer more from being born a girl (It was understood in our house that boys were superior beings) than from social rejection. She was a teenager when she realised her function was to make a brilliant marriage and so help rehabilitate the family. Her first memoir, Youth is a Blunder, of her early years, evokes what she called the casual cruelty of childhood often confined to a lonely existence with governesses (and 30 indoor servants), and only leavened by her love for exploring moors, forest and sea. She felt disconnected to her background, wanting to run like a hunted hare because, as she said, she felt that she heard a different drummer.

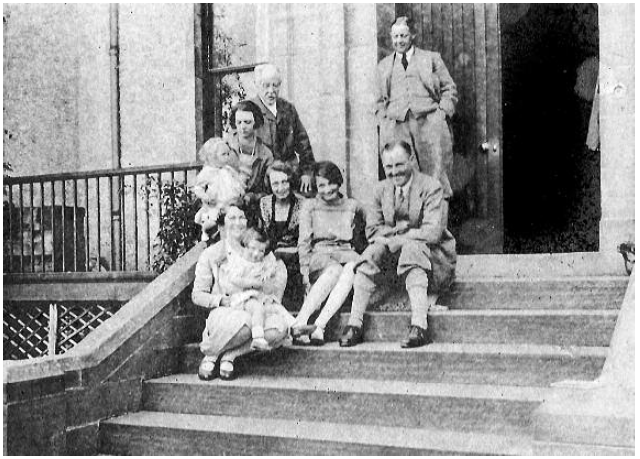

Family group at Hopeman House, Morayshire, Scotland, in 1927. Elma is in the front, with daughter Patricia on her knee. Back row: left, Sir William Gordon Cumming (father) and Alastair (brother). Middle row (left to right): Betty (sister-in-law) with her daughter Josephine; Cecily (sister), Daphne (daughter) and Roly (brother).

Then, at 18, she fell in love with a married man. When her parents found out, her mother told her no decent man will marry you now. But her mother was wrong, because a year later, she gratefully married Maurice Gibbs, an upper-class Englishman with global business connections. For nine years the couple lived in Australia, which she loved for its freedom and landscape, for a time on a sheep station exploring by car, horse and on foot the continents ferocious environment. Even so, she felt constrained by wifely duties.

Then she met Lennox Napier. He was also English, and also a businessman, but he had progressive ideas and had lived among the artists of post-Gauguin Tahiti: he introduced her to books and paintings and the world that reads the New Statesman. At first, as she wrote, she had soft-pedalled this invitation to the waltz but their relationship deepened. And in this partnership she found an answer to her restlessness. But it was at a high cost. In the wake of her divorce, she forfeited the two children of that marriage into the care of their father. (Ronald became an RAF pilot and was killed in action in 1942, while daughter Daphne would eventually rejoin her mother and, aged 20, accompany the Napiers to their new beginning in Dominica.) Elma and Lennox married in 1924.

The couple had discovered Dominica on a Caribbean cruise taken on account of Lennoxs fragile health and fell in love at first sight, an infatuation without tangible rhyme or reason, yet no more irrational than any other falling in love. At that time, it was dismally poor, sunk in colonial neglect. Indeed, some historians have argued that the small islands of the Caribbean had remained essentially unchanged since the end of slavery. But as Elma Napier evokes in Black and White Sands, her memoir of her life on the island, this was a society characterised by a self-sufficient peasantry, free to work the land and sea, unhindered by authority, and possessing a rich Creole culture. Peasant lives changed little until, after the shortages and dramas of the war years, post-war reforms brought roads, universal suffrage and some redistribution of land to this mountainous and dazzlingly green island.

Elma and Lennox Napier both played a part in these changes, in the politics of their adopted island. They may have been upper-class bohemians complete with servants, but they were not lotus-eaters, nor, indeed, were they like the sybaritic settlers of that more famous part of empire, Kenyas Happy Valley. Both became, at different times, members of the colonys Legislative Council, Elma being the first woman to sit in a Caribbean parliament. Many years later this achievement was celebrated on a Dominican stamp that bears her image.