Dedicated to the memory of

James Crawford (19482021)

and

Louise Rands Silva (19642021)

CONTENTS

What is a colony

if not the brutal truth

that when we speak

the graves open.

And the dead walk?

Eavan Boland, Witness, 1998

This is a true story, first recounted in a series of lectures I gave at the Hague Academy of International Law in the summer of 2022. As a participant in parts of it, I am not an independent observer, and understand that events may be seen from different angles, with different interpretations. I have tried to present a personal account in a manner that is fair and balanced.

The story, which is little known and deserves a broader audience, actually comprises a number of interwoven tales. One relates to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, and its role in the gradual demise of colonialism, with a focus ultimately on the case of Mauritius. Another is more personal; my own evolving relationship with the world of international law. And a third, the beating heart of this book, is the tale of Liseby Elys the wrongs done to her and other Chagossians, and their quest for justice that continues to this day.

I have sought to capture what Madame Elys shared with me, during many hours spent together going over the text and the events, to accord with her recollections. I hope that our collaboration and friendship meet her aspirations. Our backgrounds are different, yet our paths connected, through processes of law and litigation that have gradually closed the curtain on the colonial era into which Madame Elys was born and lived, and in which my working life has been cast.

In offering this account of Chagos, I have collaborated with Martin Rowson, who has provided a visual interpretation of the landmark cases touched upon in each chapter, placed in historical context.

London and Bonnieux

July 2022

The Chagos. An archipelago with a name silken as a caress, fervid as regret, brutal as death

Shenaz Patel, Silence of the Chagos , 2005

La Cour! On a summer morning in The Hague, the words were proclaimed with solemnity by a man in formal attire from whose neck hung an impressive silver chain, a symbol of authority. As practised for many decades, he announced the languid entry into the Great Hall of Justice of the judges, robed and beribboned, making their way to their respective seats in a line behind a very long table. The President, a calm man from Somalia who knew first-hand what it meant to be on the receiving end of British and Italian colonial generosity, stood at their centre. He glanced around the courtroom, looked at the assembled rows of lawyers and diplomats, journalists and interpreters, framed by vast stained-glass windows and crystal chandeliers, then invited us to take our seats.

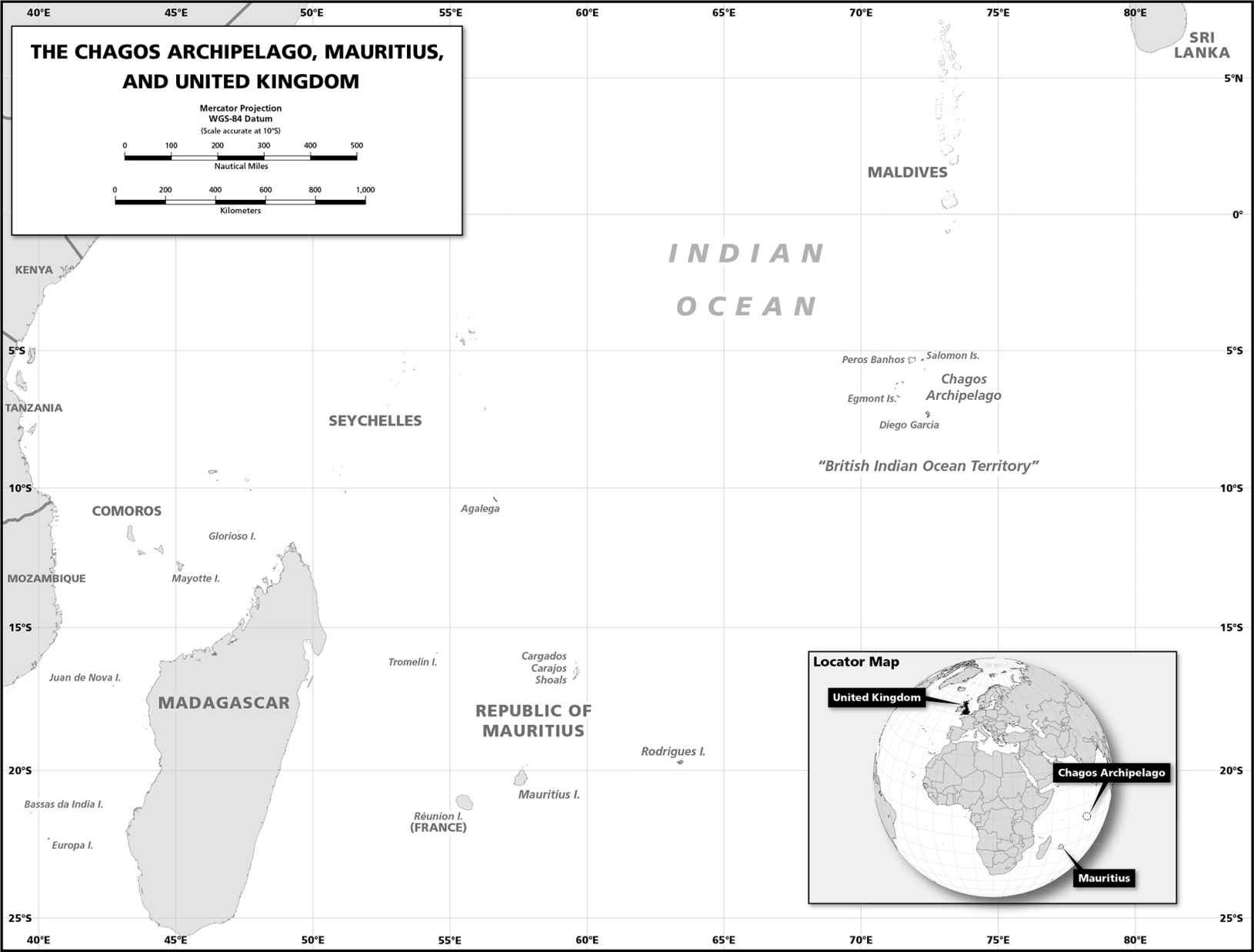

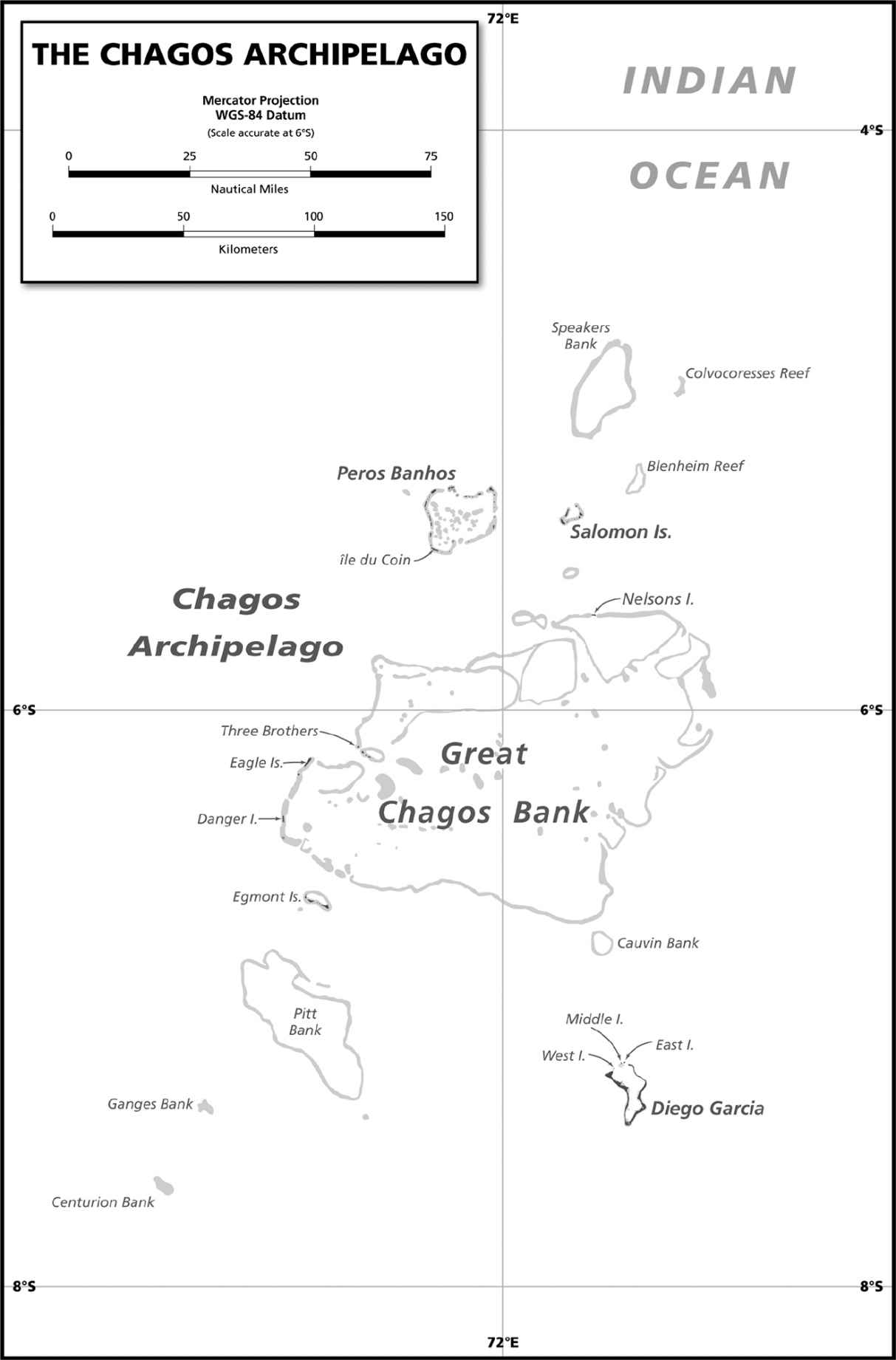

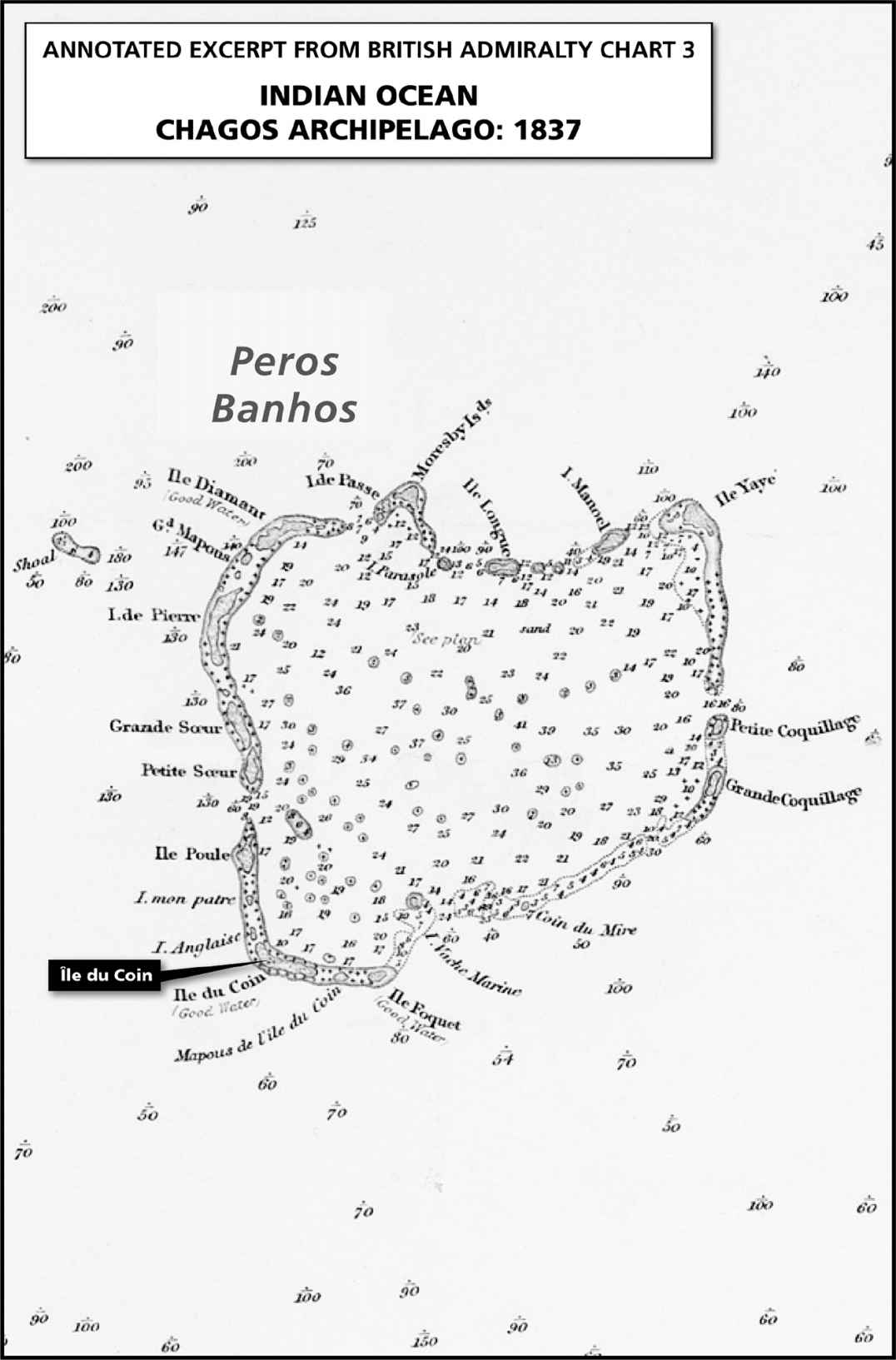

Sitting in the second row, directly behind me, was a diminutive lady dressed in black, the small handbag she clutched offering an air of formality, of dignity. She had travelled from distant Mauritius as a member of that countrys delegation. She was here to tell a story, a short tale of the early years of her life, in the hope that her account might encourage the fourteen judges in a direction that could allow her to return to the place of her birth. Home, in a real sense, where the heart is, was Peros Banhos, a tiny island that is part of an archipelago called Chagos, located in the midst of a vast Indian Ocean. From there, five decades earlier, along with hundreds of others, she had been forcibly removed.

Liseby Elys lived happily on Peros Banhos until her twentieth year. Then, without warning, one spring day she was rounded up by the British authorities, allowed a single suitcase, and ordered to board a boat that would transport her a thousand miles away. The island is being closed, she was told. No one explained why. No one mentioned a new military base the British had allowed the Americans to build on another island, Diego Garcia. No one told her that Chagos, long a part of Mauritius, had been severed from that territory and was now a new colony in Africa, known as the British Indian Ocean Territory. Madame Elys, and the entire community of some 1,500 people, almost all Black and many descended from enslaved plantation workers, were forcibly removed from their homes and deported.

She was in The Hague to participate in a case about her islands. The fourteen judges did not yet know who she was, or her role in the proceedings. They would hear arguments about Britains last colony in Africa, how it was dismembered from Mauritius, and determine whether, as a matter of international law, it belonged to Mauritius or Britain. The judges would navigate matters of history and colonial rule, traversing questions of race and rights under international law. They would confront the principle of self-determination and rule on whether a group of people could decide their own destiny, or have the course of their lives determined by others.

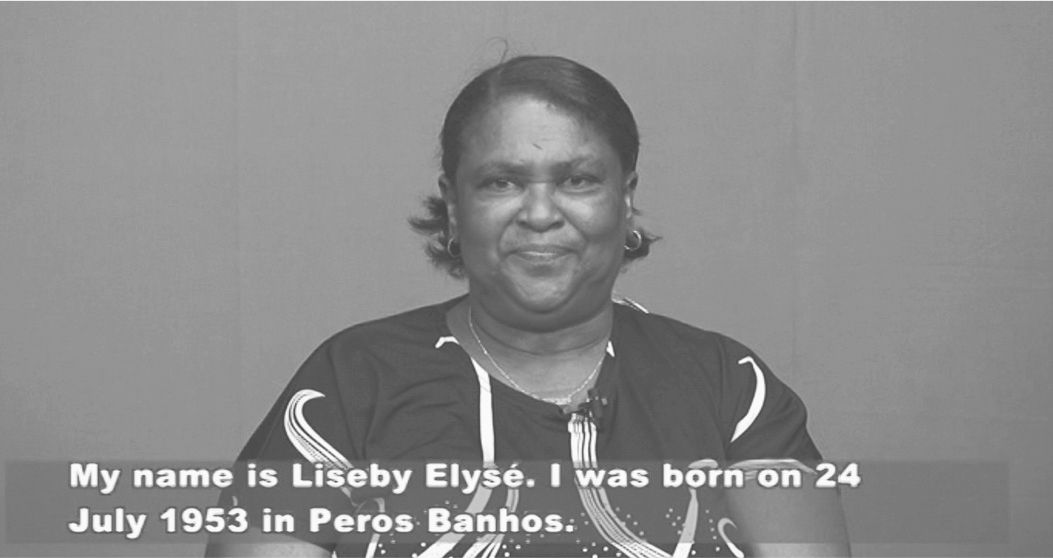

Madame Elys was a witness for Mauritius, the African country for which I acted in the case. She would speak on behalf of Chagossians, in the language of Creole, delivered with clarity, force and passion. She could not read or write, so the judges agreed she would address them in a pre-recorded statement. She would watch them as they watched her, a woman in a black suit and a white shirt edged with lace, wearing a small blue and red badge that proclaimed: Let Us Return!

The President opened the proceedings with a short summary of the case, then invited the first speaker to address the Court. Slowly, Sir Anerood Jugnauth eighty-eight years old, former Prime Minister of Mauritius, member of the bar of England and Wales, Queens Counsel made his way to the podium. He spoke for exactly fifteen minutes, followed by two advocates, a short pause caf and then a third advocate. He and the lawyers spoke from prepared scripts, which offered an air of theatre, the judges as audience. They did not interrupt, they did not ask questions.

I made my way to the podium. I had addressed the Court many times before, yet on this occasion was somehow more anxious. Madame Elys, now in the front row, stood briefly as I introduced her. The Court should hear the voice of the Chagossians directly, I explain, to obtain a sense of the realities of colonial rule.

Madame Elyss statement was projected on two large screens that hung above the judges, words and images broadcast around the world. In faraway Port Louis, the capital of Mauritius, the proceedings were shown live on national television, as her friends gathered in a community centre to watch. They would weep as she spoke.

* * *

Mappel Liseby Elys.

My name is Liseby Elys. The translation appeared in English and French, neat captions in white at the bottom of the screen.

I was born on 24 July 1953 in Peros Banhos. My father was born in Six Iles. My mother was born in Peros Banhos. My grandparents were also born there. I form part of the Mauritius delegation. I am telling how I have suffered since I have been uprooted from my paradise island. I am happy that the International Court is listening to us today. And I am confident that I will return to the island where I was born.

Next page