The author and publishers would like to thank the following institutions and individuals for their permission to reproduce illustrations:

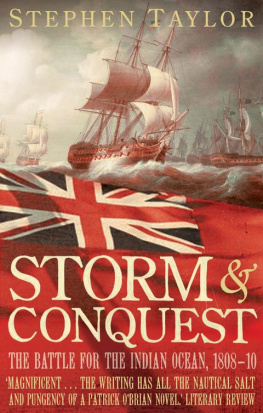

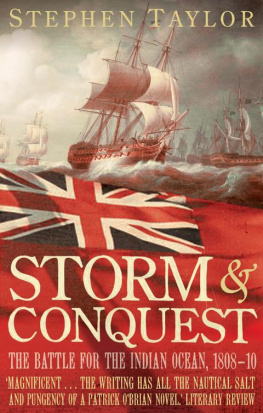

Over the first weeks of 1808, a grand and powerful fleet mustered in the south of England. For weeks Portsmouth harbour resounded by day with the hammering of carpenters, the cries of men from ships at anchor, and echoed by night with song and the stamp of hornpipes from the seamens taverns. To all outward appearances, the ships preparing to set sail for the Indian Ocean that season might have been men-of-war, for each was pierced for at least a dozen cannon and some of the larger vessels resembled the new frigates moored at the nearby Royal Navy station of Spithead. In fact, they were East Indiamen, vessels of the self-styled Grandest Company of Merchants in the World; but, although their purpose was trade, the underlying military nature of the voyage could not have been clearer.

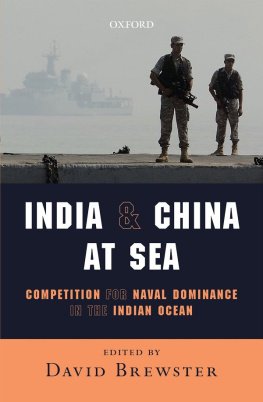

General Arthur Wellesley was soon to open up a front in Portugal against Bonapartes seemingly unstoppable march across Europe, and saltpetre, the principal ingredient of gunpowder, had become a strategic resource of the utmost importance. The East India Company fleet, bound for the Coromandel Coast, was contracted to supply the Government with 6,000 tons of Bengali saltpetre, the purest known form of the substance, and the Indiamen were to sail with a Navy escort. This was no idle precaution: while Nelsons victory at Trafalgar had left England supreme in home waters, the Indian Ocean had never been more perilous. On top of the perennial hazard of storms in the so-called hurricane season, French frigates and privateers had removed from the Mediterranean in order to prey on English shipping in the Bay of Bengal, and had done so with spectacular success. Ile de France, or Mauritius, a speck of an island in the southern latitudes of that immense ocean, was the minuscule bastion from which these raiders ventured forth; and to such effect that a dozen English merchant ships had been taken in just three months.

On the eve of 3 March, the fleet was ready. Captain Henry Sturrock of the Preston called at The George to tell his most distinguished passenger, Lady Barlow, wife of the Governor of Madras, that the wind had come about and she and her daughters might board in the morning. Well before dawn, shrouded figures gathered at the Sally Port before crunching across shingle to rowing boats. At eight oclock the first of the Indiamen weighed anchor.

Even as the land slipped away, so did the first life. John Joice, one of a hundred men of His Majestys 69th Regiment of Foot, bound for Madras, died before sunset among his comrades on the Canton. At daylight the next day his body was dropped over the side. There was no pause then, or a few days later when Eliza Gamble died on the Hugh Inglis; Eliza was aged four, the daughter of Sergeant William Gamble of the 17th Light Dragoons. But as one young life ended, another began. On the Preston it was recorded: Mrs Brooke, passenger for Madras, was safely delivered of a daughter.

Three days out they hit bad weather. The Cantons log for 8 March reads

An amazing high sea running which causes the ship to labour much and take in a great deal of water. Find great difficulty in steering. At 11pm in reefing the foretopsail, James Wilton, ordinary seaman, fell from the yard upon deck and fractured his skull, which caused his death at 4am.

As rapidly as it had come the gale departed and now, with a steady following breeze, the Indiamen rounded Lizard Point, the southernmost tip of mainland Britain, passing out into the Atlantic with the furl and snap of canvas overhead, a bawling in the rigging and the buoyant cheer of men assured that they were the boldest, finest seafarers in the world.

Over the coming months, three more fleets of Indiamen would follow in their wake. By the time an unusually balmy spring had turned to summer, a total of twenty-eight ships had set out for India to collect saltpetre for the Peninsular War. It was to be more than a year before the first came in sight of England again and the ships that anchored in the Downs the following summer were a battered remnant, the sailors a reduced and chastened band. Even the oldest hands confessed that they had never seen anything like it.

Quite what had occurred that season in the Indian Ocean took the Company months to piece together, and even then many mysteries remained. In plain terms, however, the India House had suffered the worst calamity in its shipping history. No fewer than fifteen ships had come to grief: seven simply disappeared, never to be seen again; two went aground and were lost; and six were captured by French frigates one of them twice. Thousands of tons of saltpetre for the war were at the bottom of the sea. In human terms, more than 1,000 people were dead, many of them personages.

The Directors of Leadenhall Street, whose usual demeanour was that of Elizabethan pirates, paled. These disasters were linked with that ocean speck, a place so insignificant in size that it was not represented on maps other than as a dot at Lat 20 15'S, Long 57 15'E a volcanic creation that jutted out of the sea like a row of green fangs. Then they recalled William Pitts grimly prophetic words twenty years earlier: As long as the French hold the Ile de France, the British will never be masters of India. And they resolved on action.

The story of that year is partly told in a remarkable collection of books: a series of vast slab-like volumes in gold-lettered maroon board, each the size of a medieval Bible, which cover hundreds of feet of shelf space below the British Library. These are the Indiamen captains logbooks, flaking with age, the ink fading, each bearing the hand of the keeper, each strangely opaque and yet revelatory. Each is a diary, set down 200 years ago, of life on a floating island 140 feet in length, on which around 250 souls were confined for half a year. Sometimes they are illegible. Often they make dull reading: endless entries of weather conditions, wind direction, ship routine. Then they will spring to life with incident with deaths, beatings, storms, and battles. The reader finds himself scanning pages for the tell-tale signs, dense passages of script, often scrawled hastily and in crisis, from which drama at sea emerges in all its terrifying unpredictability.

The East Indiamen were unique. They were merchant ships, they were fighting ships, and they were troopships. Yet they were also the first ships systematically to move civilian passengers around the globe a forerunner, in a sense, of the great P&O liners of a more cosseted age of travel. Every Company servant in India had this one experience in common, of a great voyage traversing two of the worlds oceans. I became intrigued by the Indiaman as a social cocoon, with life on what one writer (of fiction) called a creaking, leaking incompetent concoction of oak and pitch and nails and faith, and by images of the great cabin (which was actually quite small) where the rich and privileged, the nabobs, dandies, and military officers (an unhappy species at sea) along with their ladies and children, loved, hated, gamed, drank, feuded, celebrated, sometimes died but usually endured a confinement that lasted anything from four to eight months and which would today be found insupportable.