Introduction

W hat is the ocean? Today we refer to five individual oceansthe Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic, and Southern. But in ancient and medieval times, the ocean was the whole mysterious and frightening mass of water surrounding the only known landsEurope, Asia, and Africa. In fact, nothing separates the oceans from each other. There is no moment when one passes from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, or from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. The ocean is a great unity. As the Encyclopaedia Britannica said in 1911, it is the great connected sheet of water which covers the greater part of the surface of the earth.

Ocean voyages were made as long ago as 1000 bce , when Polynesians began migrating across the Pacific. From Europe, Viking sailors originating in Scandinavia crossed the North Atlantic to Iceland in the 9th century ce and had reached North America by 1000 ce . In the Middle Ages, sea trade routes linked China to Egypt and Venice to London. Most seafarers kept close to coastlines whenever possible, however, and for the learned scholars of the Muslim Middle East and Christian Europe, the ocean remained the subject of fear or denial. According to the Arab geographer Al-Masudi in 957 ce , the Pillars of Hercules at the exit from the Mediterranean Sea into the Atlantic had statues indicating that there was no way beyond me. The German chronicler Adam of Bremen wrote in 1076: Beyond Norway, which is the farthermost northern country, you will find no human habitation, nothing but ocean, terrible to look at and limitless, encircling the whole world. Around 1290, an Englishman, Richard of Haldingham, presented a map to Hereford Cathedral. In medieval fashion, it showed the world as consisting of three continentsEurope, Africa, and Asia. Even the Mediterranean was not accurately drawn, with a triangular Italy and the eastern end of the sea curving to the north. The band of oceans surrounding the great landmass was not much wider than the rivers and seasthe oceans were simply not considered important.

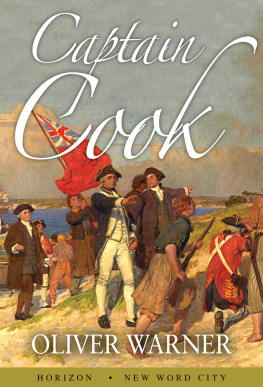

This narrow view of the world was soon to change, however. Venetian Marco Polos 1298 account of his travels in the east, including a sea journey from China to the Persian Gulf, broadened the scope of knowledge. By 1400, Europe had rediscovered the works of the ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy, written in the 2nd century ce . Ptolemy had plotted the Indian Ocean, though he showed most of India as an island and enclosed the ocean with land. In the 15th century, sailors began to explore the world more systematically. Between 1405 and 1433, the Chinese admiral Zheng He led a series of voyages into the Indian Ocean, traveling as far as the east coast of Africa. Portuguese caravels, meanwhile, began probing tentatively down Africas west coast and into the unknown mass of the Atlantic, reaching the Azores in 1427. The expanding view of the world is summarized in a great map made by the monk Fra Mauro in Venice around 1450. Fra Mauro writes that he does not believe the Sea of India is enclosed like a pond, since a junkperhaps part of Zheng Hes expeditionhad crossed the Indian Ocean in 1420 and sailed for 40 days in a south-westerly direction without ever finding anything, except wind and water. Fra Mauros map also recognized the Atlantic as an ocean. The European experience soon spread to the rest of the world. Adventurous mariners backed by aggressive and acquisitive monarchs set out in search of trade, land, and plunder. Christopher Columbus established the first sustained maritime link between Europe and the Americas with his famous voyage to the West Indies in 1492. Setting out in 1498, Vasco da Gama led a Portuguese fleet around the southern tip of Africa to India. In 1519, Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese in the service of Spain, set off on a voyage around South America, his crew completing a circumnavigation of the globe after his death in the Philippines. By 1527, a world map produced by Diogo Ribeiro gave a reasonably accurate representation of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, plus a sketchier Pacific. The age of ocean denial was over.

Once humans could travel over vast areas of sea, it was perhaps justifiable to use the term conquering the ocean. Yet for centuries, ocean voyagers confronted discomfort and danger. Land travel was not without dangers, but those of the sea were of a different order. Without prior knowledge or charts, sailors could never be sure what was under the surface of the sea. If bad weather came, it was often not possible to find shelter. Diseases, such as scurvy, killed thousands of people at sea, and accidents were commonplace in the dangerous environment of a sailing ship. Sea travelers might run out of food or water, and it was not possible for a sailor in trouble to call for help beyond the horizon. Waves often made traveling by sea intolerably uncomfortableseasickness was perhaps the greatest deterrent to ocean travel, apart from the danger.

In the golden age of sail from the 16th to the 19th century, ocean-going sailing ships were central to world trade, empire building, and warfare, yet they remained entirely at the mercy of the currents and above all the winds, which are often unpredictable even to a modern weather forecaster. A sudden gale could scatter or sink a fleet. A dead calm or adverse winds might slow or halt a voyage, adding weeks to a journey. The constancy of predictable winds was highly prized. The American seaman Richard Henry Dana, writing in 1840, described the blessed trade-winds that have blown in one direction, perhaps from the Creation, never falling away to a calm & never rising to a furious gale The other bugbear of ocean travel was the lack of navigational techniques. Observing heavenly bodies, continually measuring the ships speed, and using the magnetic compass could at best achieve a fair degree of precision in calculating a ships position. Sailors out of sight of land often had only a vague notion of where they were and the lack of accurate charts added to their difficulties, but years of technological progress and maritime experience gradually improved ocean travel. By the 19th century, scurvy was almost eliminated and navigation was greatly improved. As ocean-going steamships replaced sail in the second half of the century, sailors no longer had to rely on fickle winds and the time spent at sea was reduced. By the 20th century, ocean travel had become reasonably safe, at least in time of peace.

In a sense, the ocean has not been conquered, and never will be. Nothing we do can intentionally control the currents, waves, and weather, and human impact has mostly been negative and unwanted. But humans have at least developed the means to travel over vast areas of sea, and this achievement has been the product of many centuries of adventures. Seafarers from ancient times down to the present day have faced a hard struggle against the elements, demanding endurance, skill, and ingenuity, whether engaged in trade, exploration, warfare, or the colonization of distant shores. The record of their lives includes barely credible stories of voyages into uncharted waters and survival at sea against awesome odds. Their experience deserves to be celebrated, as does the essential contribution of sailors and their ships to the evolving history of the human world.

I n many different parts of the world, the first simple boats were built for local travel in sheltered, inland waters such as lakes, rivers, and estuaries. Voyaging on seas and oceans, however, was a far riskier venture. The Polynesians were the first ocean sailors, crossing wide expanses of the Pacific in outrigger canoes propelled by paddles and sails, while in the Mediterranean, the Phoenicians, based in what is now Lebanon led the development of maritime trade from around 900 bce , and the ancient Greeks and Romans practiced large-scale naval warfare from oared galleys. The Mediterranean peoples also operated far beyond the confines of their native seathe Phoenicians, for instance, sailed to the Canary Islands, and the Romans maintained a fleet in Britain. After the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century ce , new societies emerged in northwestern Europe, some of which developed impressive seafaring skillsthe Vikings of Scandinavia were probably the first European sailors to reach North America, for example, although they left no permanent settlements. While oared galleys remained the elite ships of the Mediterranean, medieval northern Europeans built seagoing sailing ships descended from the Viking longships, and used them for trade and war.