Contents

Guide

The events and experiences detailed herein are all true and have been faithfully rendered as I have remembered them, to the best of my ability. Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Though conversations come from my keen recollection of them, they are not written to represent word-for-word documentation; rather, Ive retold them in a way that evokes the real feeling and meaning of what was said, in keeping with the mood and spirit of the event.

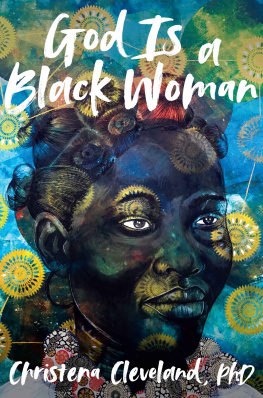

GOD IS A BLACK WOMAN . Copyright 2022 by Christena Cleveland. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Cover painting: Delita Martin

Cover design: HarperCollins; detail art: Shutterstock

FIRST EDITION

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available upon request.

Digital Edition FEBRUARY 2022 ISBN: 978-0-06-298880-5

Version 12292021

Print ISBN: 978-0-06-298878-2

for Des

If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of Him.

James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time

Gods die. And when they truly die they are unmourned and unremembered. Ideas are more difficult to kill than people, but they can be killed, in the end.

Neil Gaiman, American Gods

The white fathers told us: I think, therefore I am. The Black Mother within each of usthe poetwhispers in our dreams: I feel, therefore I can be free.

Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider

Contents

T he terror exploded in my gut as soon as I heard the police sirens in the distance. They were coming for me.

Just moments earlier, I had crossed the cobblestone square in the quaint town of Mauriac, France, and entered its fortresslike basilica. As I examined the cavernous interior, I was aggressively confronted with signs forbidding visitors from trespassing beyond the crimson velvet ropes surrounding the towns renowned sixth-century statue of the Black Madonna, an uncommon dark-skinned version of the Virgin Mary. Even with my flailing grasp of the French language, I understood that if I disregarded the signs, I risked setting off the churchs alarm system. But the ropes hung more than forty feet from the magnificent unapologetically-Black-and-female Madonna.

My unapologetically Black-and-female body longed to be near this Black Madonna, whom people of diverse races, religions, and eras have recognized as a Black and female image of God. Though I was raised in a Black family and had spent significant time in Black church spaces, the image of a white male God permeated my being. I know I am not alone. The late Black tennis star Arthur Ashe shared his childhood experience with white male God with a reporter from Sports Illustrated, who wrote: Every Sunday, Arthur Jr. had to go to church, either First Presbyterian or Westwood Baptist, where his parents had met and where he would look up at a picture of Christ with blond hair and blue eyes and wonder if God was on his side.

Like Arthur Jr., I too questioned whether God was on my side. And after years of questioning, healing, and transformation, I had traveled all the way to the heart of central France to finally come face-to-face with the Black Madonna. Desperate for a divine image that I related to and breathed hope into my experience as a Black person and as a woman, I had to be near this likeness of God that looked like me. Seeing Her from a roped off distance wasnt enough. I longed to gaze into Her mysterious and kind eyes, to witness Her unyielding clutch on Her precious Black boy, to run my fingers along Her centuries-old dark, wooden body, and to stand before a sacred image of Black femininity.

Eyeing the security cameras conspicuously aimed at the altar, I assessed the risks. On the one hand, I knew from experience that Black people and women are especially punished when we disregard rules. On the other hand, I knew that Black people and women are especially punished whenever we do pretty much anything. We live in a world that punishes usfor having opinions, for existing, for taking up space. As I stood at the edge of the Black Madonna of Mauriacs altar, I recalled the numerous beatings I had endured as a Black woman, much like this one:

I cant tell if youre sloppy or mischievous.

Those were the words a male audience member publicly said to me at the end of my academic lecture at Cambridge University. Drawing on my expertise as a social psychologist and theologian, I had just exposed the rampant racism in a famous Cambridge scholars work and the scholars fanboys were all up in arms. (I mean, how dare I critique their precious intellectual idol?) One fanboy attacked:

I cant tell if youre sloppy or mischievous.

Rather than offering a legitimate critique of my lecture, he fired off a racial-gender slur that cut to the core of my identity as Black and female. Sloppy is a delegitimizing stereotype launched at Black people. Sloppy, dirty, lazy, worthless; these are some of the labels society uses to brand us. And ever since good ol Eve in the Garden of Eden, women have been saddled with the mischievous stereotype, especially when we disregard social norms and do unthinkable things like call out a scholars racism. Mischievous, deceptive, untrustworthy, morally weak; these are the labels that society uses to bitch-slap us into submission.

I cant tell if youre sloppy or mischievous.

Right off the bat, as if it were already locked-and-loaded, his attack on my Blackness and femaleness was so precise, he might as well have said, I cant tell if youre Black or female.

I cant tell if youre sloppy or mischievous.

The memory of such beatings continued to clang in my soul as I stood in the basilica of Mauriac just forty feet away from an ancient statue of the divine Black and female One, who is neither sloppy, nor mischievous. There She stood, head held high, Black skin glimmering in the candlelight, Her fierce gaze a declaration to the whole world: Go on, I dare you to call me sloppy or mischievous.

Yeah, I murmured to myself. No rope or threat of alarms is gonna stop me from getting near Her.

I removed my walking boots so as not to soil the carpeted altar and lifted my sock-covered foot to step over the rope barrier. As soon as my big toe crossed the vertical plane, a ferocious, ear-piercing, pew-rattling alarm sounded. Knowing I only had seconds before I was discovered, I made a mad dash across the length of the altar to kiss Her wooden feet and quickly look up to receive Her gaze, half expecting Her to shoot me an approving wink.

Harsh emergency lights illuminated the once-dark sanctuary as I ran back across the rope and scrambled to pull on my boots. By the time I reached the basilica door, I could hear the faint but familiar NEE-yoo-NEE-yoo-NEE-yoo-NEE-yoo sound of French police sirens coming for me. My heart rate quickened as I thrust open the heavy wooden-and-iron doors, stumbled into the ghost-townlike plaza, and frantically searched for a place to hide out. I could hear the sirens coming closer, but there was nowhere to go! In every direction, all I could see was a deserted cobblestone square, empty post-tourist season sidewalk cafes, and shuttered shops.