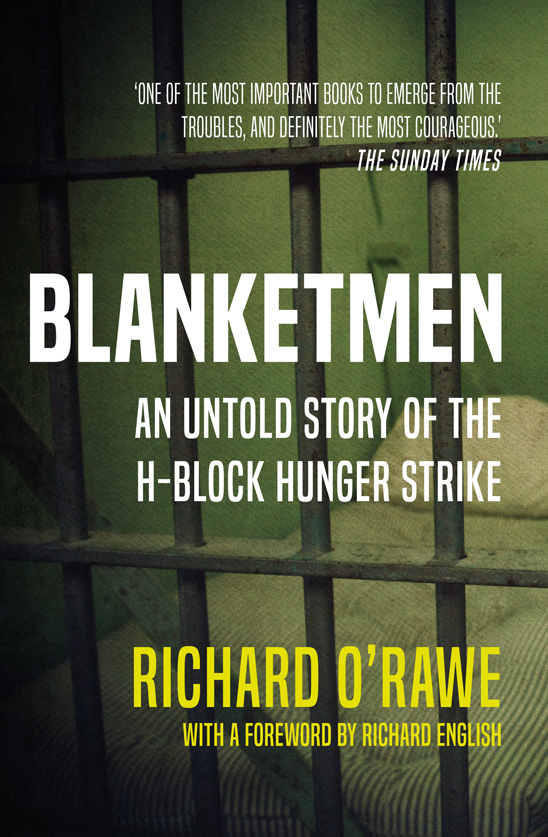

Praise for Blanketmen

Blanketmen is a brave and penetrating insider account of the 1981 hunger strikes that completely overthrows the narrative that Sinn Fin has attempted to impose. One of the most important books to emerge from the Troubles, and definitely the most courageous.

John Burns, The Sunday Times

One hopes that, whatever the outcome of the present crisis in the peace process, the hunger strike will never again be used as a tactic by either side of the conflict, and that anyone who considers it will first all be obliged to read Richard ORawes searing chronicle.

Deaglan de Breadun, The Irish Times

At the core of this very important book lies a terrible truth six men died to enable a political project to come into being. Richard ORawe deserves praise for his courage in stating JAccuse and charging one of the most cynical political leaderships anywhere on this island with manipulating the courage and determination of the hunger strikers.

Henry McDonald, Guardian

You think you know what a thing is like, and then you read an insider account and you are left reeling. There is a wealth of detail here that remains in the mind long after the book is put away. Read this book and salute the hunger strikers.

Nell McCafferty, Derry Journal

This is a really gripping book, and an important one too for an understanding of the dynamics both of the 1981 hunger strikes and the rise of Sinn Fin as a political force.

Maurice Hayes, Irish Independent

This powerful, provocative and often stark book deserves a wide audience. It is thought-provoking, not just in terms of the nature and course of the hunger strikes and the people who starved themselves to death, but also in terms of the authoritarian nature and structure of the Irish republican movement.

Diarmuid Ferriter, Sunday Tribune

BLANKETMEN

BLANKETMEN

An untold story of the H-Block hunger strike

Richard ORawe

Foreword by Richard English

BLANKETMEN

First published 2005

This edition published 2016 by

New Island

16 Priory Office Park

Stillorgan

Co. Dublin

www.newisland.ie

Copyright Richard ORawe, 2005

Foreword Richard English, 2016

The author has asserted his moral rights.

Print ISBN: 978-1-84840-554-7

ePub ISBN: 978-1-84840-555-4

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-84840-556-1

All rights reserved. The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means; adapted; rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owner.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Go tell the Spartans, thou who passeth by,

That here, obedient to their laws, we lie.

Epitaph for the Spartans who died at Thermopylae Simonides, c. 556468 bc ;

attributed, Herodotuss Histories

FOREWORD TO THE 2016 EDITION

BY RICHARD ENGLISH

Irish republican memoirs have long offered rich evidence regarding political history in Ireland, especially in relation to political violence and its contexts and aftermath. From Ernie OMalleys evocative War of Independence autobiography, On Another Mans Wound (1936), to Peadar ODonnells mischievous Civil War jail memoir, The Gates Flew Open (1932), onward into more recent years of Northern resistance, republican activists have provided reflection, argument, analysis, recollection, and much personal insight regarding Irish struggles. From the modern Troubles era there are now shelves containing different kinds of necessary reading, written by such people as Danny Morrison, Laurence McKeown, Anthony McIntyre, Patrick Magee, Tommy McKearney, and Gerry Adams.

Much of this material from Peadar ODonnell and Ernie OMalley to Anthony McIntyre in more recent times has been produced by people who have broken from the mainstream or orthodox republican movement, whether in the Civil War of the early twentieth century or through the later peace process politics of the North. And much of it also relates to prison. This current book again fits such a pattern. On its initial publication in 2005, Richard ORawes Blanketmen caused a famous furore, centred on claims made about the 1981 hunger strike. Having then been IRA Public Relations Officer for the prisoners, ORawe now claimed that an offer made by the British after only four hunger strikers had died was judged by leading prisoners to have contained enough for the strike to be called off, but that the IRA authorities beyond the jail had overruled them and insisted instead on the strike continuing.

Available evidence makes clear that a substantial British offer was indeed available prior to the death of the fifth hunger striker (Joe McDonnell). Whether the republican movement was well advised to reject it remains a matter of sharp dispute, and is likely to do so for years to come. Some would argue that the final six strikers died needlessly. Others might suggest that in a revolutionary struggle there are complex choices to be made, and that there can be high yet necessary costs to be paid for certain kinds of political momentum.

What is not open to debate, however, is that anyone wanting to understand those grim years of prison war must engage with Richard ORawes important first-hand account.

This new edition of the book brings again to our attention a compelling and personal narrative of republican struggle from a former IRA man with a very distinctive voice. The hunger strike controversy is obviously significant. But it has always seemed to me that this book is more important for its wider insights into republican activism and legacies.

For many aspects of non-state political violence and rebellion are illuminated colourfully here, including recruitment, ideology, motivation, and the ending of violent campaigns. Richard ORawe was just seventeen years old when he joined the Provisional Irish Republican Army in 1971. His father had been a republican for many years and, though not all Provos came from this kind of background, in Richards case it does illuminate one aspect of his inheritance and trajectory.

That republican journey was not heavily or formally ideological. In his own words, Although I was ideologically committed to the cause, for me, in many ways, being in the IRA was almost the objective rather than the means.

Indeed, it was in prison in the H-Blocks (by which time he was already an IRA man) that ORawe first really encountered systematic thinking about Irish republicanism as a structured ideology. Yet, despite this, there was also within the movement a deep attachment to Irish republican tradition: among the prisoners, as ORawe puts it, for example: There was an almost biblical reverence for the 1916 Proclamation. Again, Richard ORawes prison comrades in the 1970s and 1980s were often devout socialists.

Complementing family and ideology was the crucial role of a sustaining comradeship. ORawe refers to the sense of belonging offered by IRA membership and, associated with this, there was the vital phenomenon of pride. There was pride in struggle: I felt proud to be a Blanketman. And there was deep pride in IRA friendship: I am proud that I knew Bobby Sands and could call him and his fellow hunger strikers my good friends and comrades. ORawe adds, indeed, that, despite all the heartache, I am enormously grateful that God gave me the opportunity to have known those men.