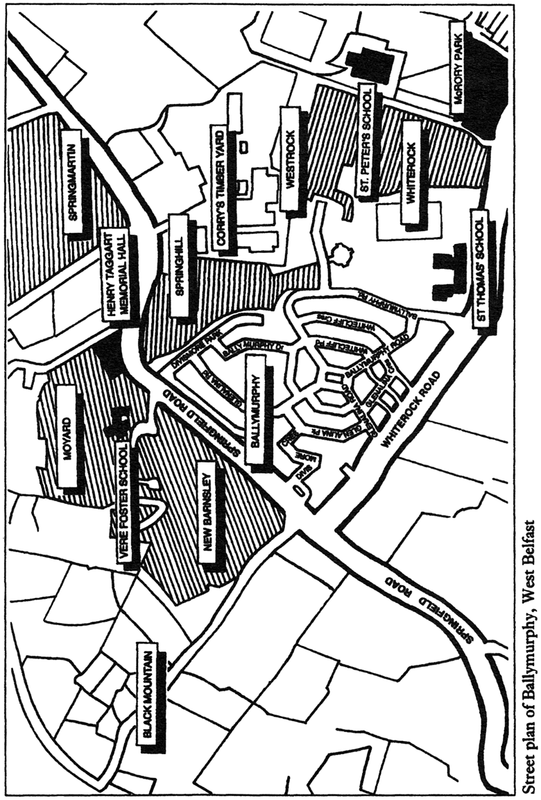

Flared behind the Black Mountain.

I want to thank Michael OBrien and The OBrien Press for reprinting Before the Dawn. The original publication in 1996 owes much to the late Steve MacDonogh of Brandon Books, who was my publisher for almost thirty years. Steve died suddenly in November 2010. He was deeply committed to free speech and against censorship. He campaigned in support of Salman Rushdie on the one hand and against the secrecy of the British state on the other. He was also a fine writer himself, a very good poet, a keen photographer and a champion of the unique community and culture of the Dingle peninsula. His contribution to Ireland, the arts, and to the world of publishing and free speech was immense, and he is sadly missed. Ar dheis D go raibh a anam.

The end of 1995 was another of those crisis moments in the peace process. U.S. President Bill Clinton made his first visit to Ireland amid intense efforts to unlock the political impasse. In a small space in the midst of all the endless negotiations, I travelled to Steves home in County Kerry to complete the final draft of this book. His advice, and the peace and quiet of his isolated home along with some very late-night sessions ensured that I eventually finished it.

While the Epilogue in Before the Dawn (see p. comes just after the thirty-fifth anniversary of that momentous event, as well as the centenary of the 1916 Rising. The celebrations of the centenary of the Proclamation of the Republic were deeper, more popular and more meaningful than the Irish government initially intended. The courage of the men and women of that time was widely and proudly remembered. So was the unique historic and still relevant 1916 Proclamation.

For those of us who survived the decades of war, the hunger strikes of 1981 were our Easter 1916. It was a transformative, watershed moment in our lives, but also in the struggle for Irish freedom. Just like those who died in 1916 in that brief, epic Rising, or those who were executed afterward by the British government, the ten men who died on hunger strike in 1981 are heroes. In their painful deaths watched daily by family and friends, and reported on by a generally hostile media they defied the Thatcher governments efforts to criminalise them and the struggle that they were proud to be part of.

When the hunger strikes ended in October 1981, it appeared that the prisoners had lost. But within a few short years, their demands were met. The hunger strike also internationalised the struggle in a way that nothing else had, and it saw a huge growth in the number of republican activists in Ireland. From the USA to France to South Africa to the Middle East and around the world, the name of Bobby Sands and the struggle of the prisoners was closely followed. On the day Bobby died, Nelson Mandela wrote in his prison calendar in his cell on Robben Island: IRA Martyr Bobby Sands dies. The hunger strike also helped accelerate the acceptance by republicans of electoralism as part of strategy. All of this opened up significant new opportunities, including secret contacts with the British government initially under Margaret Thatcher, and then John Major and efforts by Sinn Fin to explore the potential for a peace process.

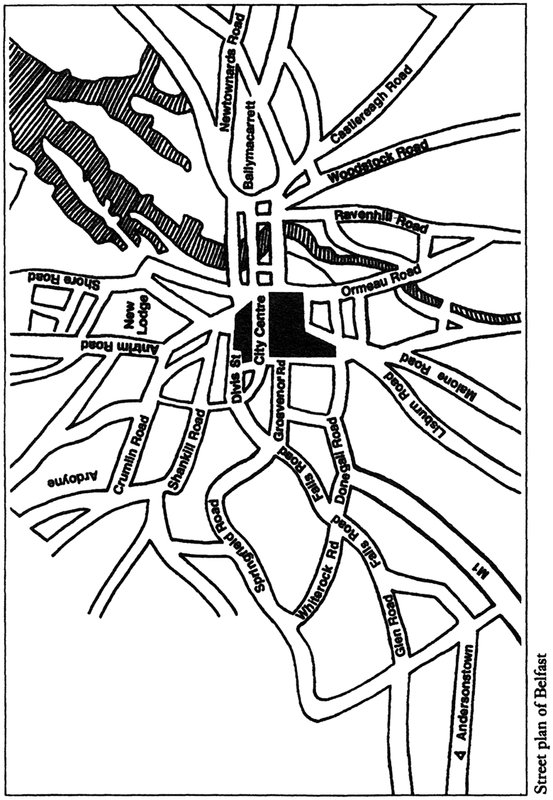

Before the Dawn tells the story of the years leading up to those events. It is my account of being a teenager and a young man growing up in the Ballymurphy area of west Belfast in the apartheid northern state the Orange State. It tells of my political awakening assisted in part by Ian Paisleys reactionary and sectarian rhetoric and actions and of some of the events during the 1960s and 1970s that shaped my life and the communities that live here.

Its about the Belfast of the 1950s and 1960s and 1970s the music, going to school, spending time with family and friends, working as a barman and exploring the Belfast Hills.

I did consider rewriting or adding material about my family, particularly my father and brother Liam, but I decided against this because the original text, as reprinted here, reflects my feelings at the time of writing. If ever I write about my abusive father, it will take more time and consideration than I have now. It will also have to take account of the feelings of others; my family circle was deeply affected by the negative political and media focus that followed revelations of the sexual abuse of my niece ine by her father, my brother Liam.

Before the Dawn is mostly about the nature of the northern state, the actions of the unionist regime, the oppression of nationalists and republicans and our response, and the first decade of conflict.

The Government of Ireland Act, imposed by the British in 1920, partitioned our island. It created two conservative, mean-spirited states. The unionist regime in the northern six counties depended upon sectarianism, the gerrymandering of local electoral boundaries, restrictions on the right to vote, and the imposition of a permanent state of emergency. Discrimination in employment and housing was endemic. It was an apartheid state.

It was little wonder that B.J. Vorster, the South African Minister for Justice in the apartheid regime, while introducing a new coercion bill in 1963 commented that he would exchange all the legislation of that sort for one clause of the Northern Ireland Special Powers Act.

In the mid-1960s I joined Sinn Fin, which was then a banned party. To get around this, we established the Republican Clubs, which for a time were also banned. I was also active in housing action agitation and protests against apartheid and the war in Vietnam. Out of the efforts of civil rights advocates over several years, the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was established in January 1967. I participated in the meeting that formally set it up.

The civil rights campaign was inspired by the American Civil Rights Movement and consciously fashioned itself on it. Irish rights activists identified with the plight of African Americans: we each were discriminated against in employment and housing and voting rights; and we each had to endure the physical and legislative oppression of special laws that banned music and literature and newspapers and peaceful protests.

The Orange state reacted violently to the peaceful protests of the civil rights movement. It employed its state police, the RUC, and its armed militia, the B Specials, to suppress peaceful demonstrations. Subsequently, in separate incidents, Francis McCloskey, Samuel Devenney and John Gallagher were killed. The Battle of the Bogside in August 1969, which began with a triumphalist Orange march along the walls of Derry, and the pogrom against Catholic working-class districts in Belfast, in which hundreds of homes were destroyed, set the scene for the decades of conflict that were to follow.