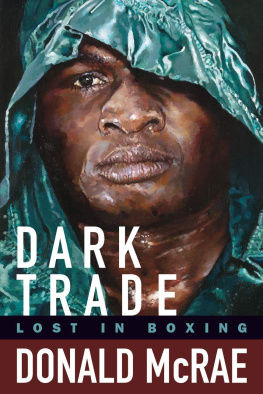

To my parents, Ian and Jess McRae,

and to my sister, Heather Simpson,

who died far too young on 15 September 2018

PROLOGUE

The Holy Family

I n the blistering summer of 2018 the vivid murals still look ominous. The brick wall facing the Holy Family Boxing Club in New Lodge, Belfast, is painted white, with green and orange trim completing the colours of the Irish flag. In its left-hand corner an IRA gunman in a balaclava looks down at the rifle that has slipped from his hands. A hooded IRA soldier stands to attention in the opposite corner. His head is bowed as he holds his gun.

In the centre of the wall two clenched fists hail the words Comrades in Resistance. On either side of this slogan a stark sentence is split in two and inked into the wall:

I dont care if I fall

As long as someone else picks up my gun and keeps on shooting.

Next to it another mural depicts three gunmen, dressed in black, pointing their rifles at a blue sky. The Irish words Tiocfaidh r L (Our Day Will Come) and Saoirse (Freedom) are painted in gleaming white. Surrounded by tower blocks and rows of council housing, the murals are reminders of the violence and pain that remain in this corner of north Belfast.

Ten minutes earlier, ambling through the Cathedral Quarter, drifting past bars and cafs filled with bearded hipsters and beautiful girls showing off their tattoos and piercings, I had been in a different world in a city full of warmth and hope for the future. It is hard to believe the Holy Family and the IRA murals are just a short walk away.

I had strolled alongside Davy Larmour, a Protestant fighter who had been trained by the venerable Gerry Storey at the Holy Family in the 1970s. Davy, a short but strapping man in his mid-sixties who had once been the British bantamweight champion, still cut an imposing figure. But his eyes twinkled beneath his bald head and above his boxers nose as we left our usual caf at the MAC, the Metropolitan Arts Centre, on Exchange Street.

I liked being at the MAC and at other places in this vibrant new Belfast. At the MAC you might see a Gilbert & George exhibition or work created by Irish, Croatian, Turkish or Palestinian artists. There could be stand-up comedy, video installations or a new play.

My head still hummed with the stories Davy told me. He had lived a different life to the Belfast millennials we passed. Many young people in the Cathedral Quarter would have looked at home in Berlin or Copenhagen. But Davy was rooted in Belfast. He was shaped by the past but he had found a way to transcend the Troubles.

Davy came from near the Shankill Road, a defining marker of Protestant Belfast, but he had also been a champion amateur boxer, and then a professional fighter, with many friends in Republican Belfast. He remembered the IRA car bomb that had blown up his fathers truck in 1972 on Ann Street, less than a mile from where we sat. Davys dad had survived, but life had never been the same again. Yet there was neither bitterness nor resentment in Davy.

He was happy to hear I was on my way to see Gerry Storey at the Holy Family.

During my earliest visits to the city, not knowing the geography of Belfast despite being aware of the New Lodges reputation, I would take a taxi from my hotel in the Cathedral Quarter to the Holy Family. It was never more than a 5 fare but we had to go the long way round. I learnt later from Gerry, who had run the gym for over 50 years, that I could walk to the Holy Family just as quickly by strolling up North Queen Street, crossing over at the McGurks Bomb memorial and taking the walkway round the back.

The first time I took the short cut, Gerry led me down the grimy stairwell. We crossed the road under the concrete flyover and stood outside the painted exterior of McGurks Bar. On a desolate night in 1971, Gerry had lost friends at McGurks and his family had felt grief and rage. A week later there was a retaliatory bomb, aimed at Protestants on the Shankill Road. Four innocent people were killed; Davy Larmour just missed the explosion.

Gerry gave me these lessons in Irish history with a light touch. He also explained how his peaceful work overcame deadly bigotry. In the 1970s and 80s he had criss-crossed Belfast, moving from Republican to Loyalist no-go areas with relaxed good cheer as he trained both Catholic and Protestant boxers. Gerry and his fighters were different to anyone else during the Troubles. They were allowed to travel freely and were welcomed everywhere in a battered city. He put on boxing shows deep within gunmen territory whether the paramilitaries were from the IRA (Irish Republican Army) or their enemies in the UDA (Ulster Defence Association) or UVF (Ulster Volunteer Force).

We moved on, walking through New Lodge, and Gerry glowed with the memory of all he had done and the men he had made, from world and British champions like Barry McGuigan and Hugh Russell to lesser-known characters he celebrated with equal fervour. The more we walked, and talked, the closer I felt to this extraordinary story. I saw the ghosts of a brutal past and I understood the peril and hatred Gerry Storey had withstood.

I told Gerry again about my own history. I had grown up in South Africa under apartheid. When I was in my early twenties in the 1980s, we heard intricate reports about Northern Ireland on our daily news bulletins. It was almost as if the government and the state broadcaster, the SABC, wanted us to realise that other countries were afflicted by division and strife.

We heard much about Bobby Sands, the IRA hunger striker in the Maze prison near Belfast, but nothing about Nelson Mandela serving a term of life imprisonment on Robben Island. We heard much about riots and bombs in Belfast and Derry, but only controlled snippets of the dissent in the black townships of Soweto and Alexandra. We heard much about bloody conflict between Catholics and Protestants, but just censored versions of the war in the townships and along South Africas borders with Mozambique and Angola.

Decades later, in the 21st century, lessons learnt from South Africas post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission helped the peace process in Northern Ireland. Republicans, Loyalists and policemen from the Royal Ulster Constabulary had travelled together to Cape Town in 2012. They had once wanted to kill each other, but in South Africa they found a way to talk as they met with delegates from the TRC to discuss how they might break free from a violent history. Northern Ireland has always mirrored my old country.

I had been thinking about Storey for years ever since Id heard how he had taught boxing in the Maze prison in the immediate aftermath of the hunger strikes. In 1981, Sands and nine other Republicans had starved themselves to death in a battle against Margaret Thatchers government. That crisis had gripped and appalled me 6,000 miles away in Johannesburg. I had since learnt that Storey had gone into the Maze, where the hunger strikers had died a few months earlier, and given boxing lessons to prisoners from both the Republican and Loyalist cages.

I did not know then I would spend years researching this book. In Derry, I spent many days with Charlie Nash, the first significant boxer of the Troubles, a man who fought for European and world titles despite the tragedy his family endured on Bloody Sunday. I became friendly with Larmour and Russell, a Protestant and a Catholic who shared two bloody battles during the early 1980s. Russell was an Olympic medallist for Ireland and a British bantamweight champion. He was also one of the great photographers of the Troubles, who documented the carnage with his camera by day while sparring in the gym at night.