Contents

Guide

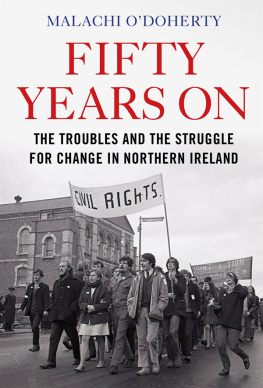

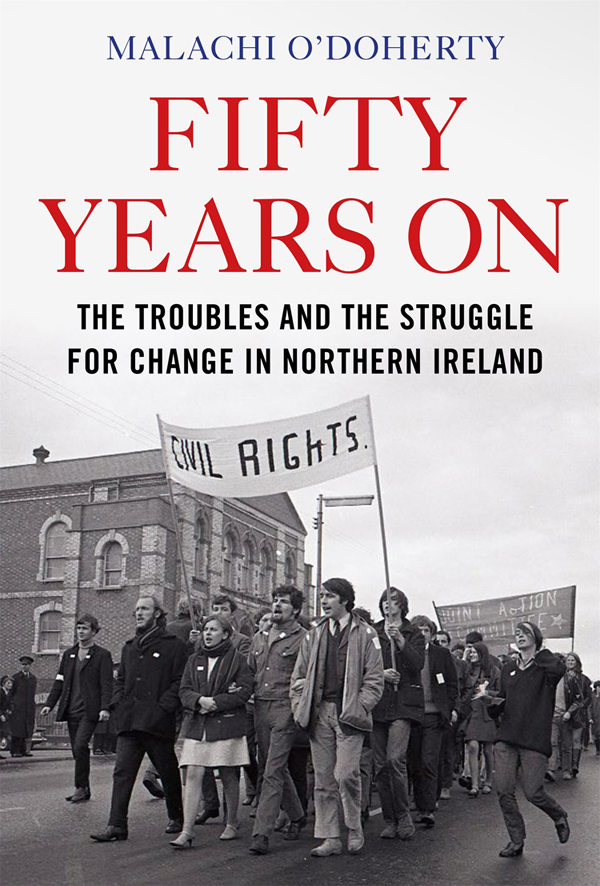

Fifty Years On

By the same author

The Trouble with Guns

I Was a Teenage Catholic

The Telling Year: Belfast 1972

Empty Pulpits

Under His Roof

On My Own Two Wheels

Gerry Adams: An Unauthorised Life

Fifty Years On

The Troubles and the Struggle

for Change in Northern Ireland

Malachi ODoherty

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Malachi ODoherty, 2019

The moral right of Malachi ODoherty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All photographs are reproduced by permission of the author.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-664-5

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-665-2

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-666-9

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

for

Ciaran Carson

CONTENTS

Prologue

I have made it to my bed but I do not feel safe. The shooting continues. Not up close distant but heavy. I now believe it is real; at first I didnt. When I was walking away from the rioting on Divis Street I was stopped by two American journalists who asked me if there had been any gunfire here yet.

I said, Only blanks.

Why did I say that? What did I know about what people were doing, how bad this would get? I had no insights into the organisation of the riot, no familiarity with the people who led the attacks on the police. But I just assumed that this skirmish would be like others I had seen; and if there was the odd crack or rattle that might have been a gunshot, I had heard these before and no one had suffered bullet wounds or seen holes in walls or windows afterwards. So, pretending to understand the pattern of trouble that had become familiar over the past year, I said no, only blanks.

When I heard machine-gun fire, there was no mistaking it. It was murderous. You wouldnt confuse that with fireworks or something falling over. You could hear the clear intentionality of it in the blunt, abrupt, clean dunts, like rapid hammer blows. I had left Jo to the bus station. We had not been able to go down the Falls Road, so we had detoured to the south of the city and taken a bus along the Lisburn Road and walked across town. We saw a huge water cannon trundle across King Street in front of us, and heard the clatter and banging and shouting further away. She scoffed at the mob. If they had jobs to go to tomorrow they wouldnt be at that carry-on.

She is a protestant and comes at this differently. For one thing, she knows more people in the police, for very few catholics are in the Royal Ulster Constabulary none at all in the Special Constabulary, those part-timers who were called up tonight for back-up. So she has more sympathy with men in uniform.

Her family probably votes for the Unionist Party, which has been in unbroken control for fifty years and which is challenged by these riots and the demands for civil rights. She doesnt believe that teenagers chucking petrol bombs at the police care a fig about civil rights: they are out enjoying themselves. Shes probably right.

I left her to the bus and came back. There were about a dozen of us watching. It was some show. Police in black uniforms with shields confronted young men throwing bricks and petrol bombs at them. The bombs were milk bottles, which arced through the air then smashed on the ground and produced a sliver of flame.

This was all under the view of Divis Tower and there were men on the roof. I watched them throw down a whole crate of bottles, smashing them on the ground. I thought at first they were just discarding them, making a racket, but as the rioters pulled back and the police charged, I saw what they were up to. One of the men on the roof dropped a petrol bomb into the mess and whoosh, it went up in flames.

I saw a young man in a pink cheesecloth shirt and jeans being grabbed by two policemen and led back behind the lines in front of us to the station. The police had their sneaky strategies too. They would pull back, closer to us, and entice the rioters into the range of armoured cars parked in Conway Street and Dover Street. These werent like the big water cannon. A man near me in the crowd called them whippets. They were small, almost pyramid-like on top. They had mounted machine guns. They whirred and they spun. Two came out from different directions to break up the rioting mob and then the police launched a baton charge after the scattered men and brought one or two down with a strike at the knees and pulled them in.

I saw a delivery van for a sausage factory pull up on our side of the line and special constables with rifles climb out the back and rush along the wall into the police station. A senior officer in ordinary uniform, with a peaked cap, not a helmet, came and spoke to us. I urge you to disperse. We cannot guarantee your safety. This is getting much more serious.

They should bring in the army, said the man beside me. Theyd soon show them. Theyd throw their petrol bombs back at them.

I left the group and went back the way I had come with Jo. The buses were all off now.

That was when I met the Americans and reassured them, and they must have marvelled at my innocence, my ignorance.

*

I walked up the Grosvenor Road, to join the Falls Road on the other side of the riot, anticipating a three-mile walk home. I had turned the corner on to the Falls when I heard the first string of blurts from a machine gun. At first I had no idea where it had come from. There was another.

I was passing the front of the hospital and worked out that there must be a sniper on the roof, for the noise of the gun was so loud it seemed almost beside me. I ran into the front of the hospital for cover and faced the double escalator. Both sides were coming up now. There was no way in. I wondered if my panicked mind was hallucinating. I was fired with urgency not debilitated by terror, as I would have expected. I was studying everything and reading my reactions. Even as I turned and ran up the road, close to the front of the hospital, I was registering an insight: that if Jo had been with me in those moments I would have been no use to her. Then I walked with my head down, but the shooting started again. Bop-bopbop-bop-bop. A couple of boys on the other side of the road started running for cover along the stone wall of the convent school, St Dominics.

I ran. And as I did so a car pulled up ahead of me; a man jumped out and grabbed me by the arm and with his other arm pressed my head down. Keep low. And he ran with me to the car. There was a young fella in the back seat. They drove me home. We passed groups of people at bus stops, apparently still thinking there was some normality there. There was. The man and I did not talk about the gunfire or the politics. He just said, Your mother will be worrying about you.