For my parents

and for a special family

who have made me proud

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

www.facebook.com/mercier.press

Michael McCann, 2019

ISBN: 978 1 78117 619 1

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 620 7

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 621 4

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

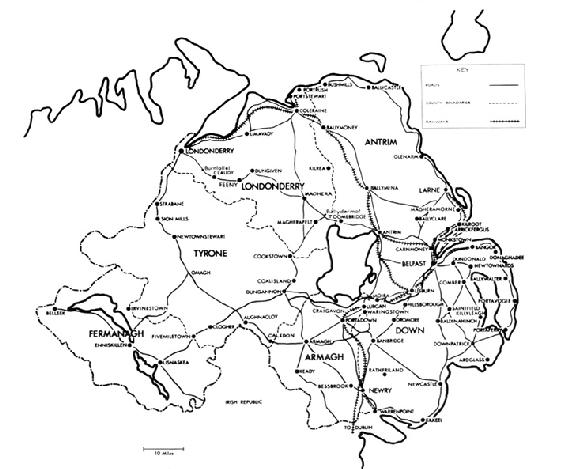

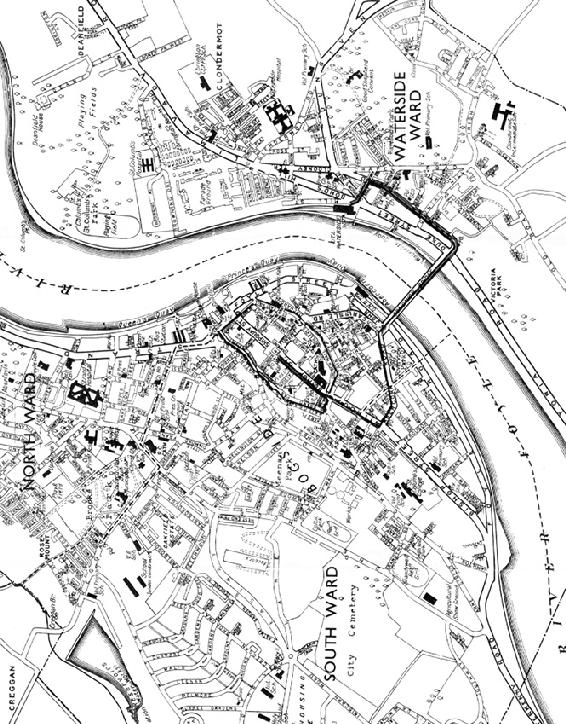

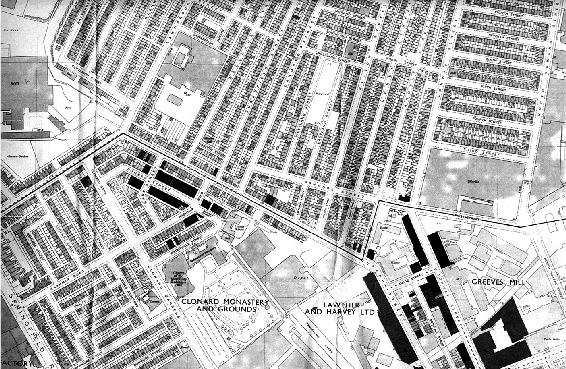

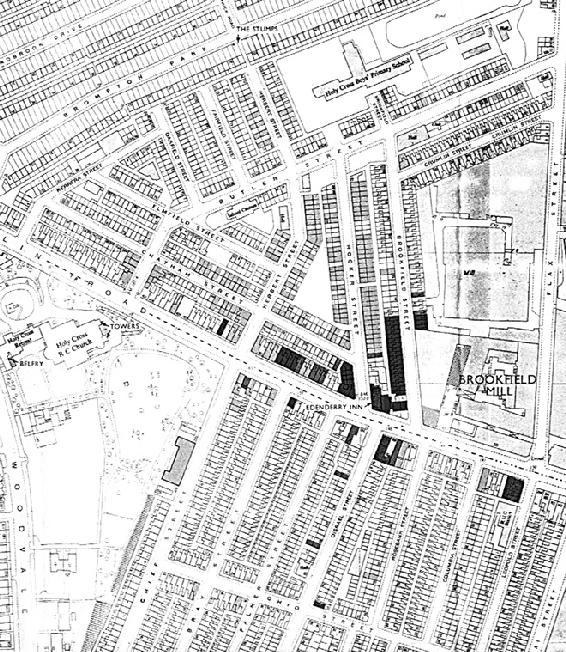

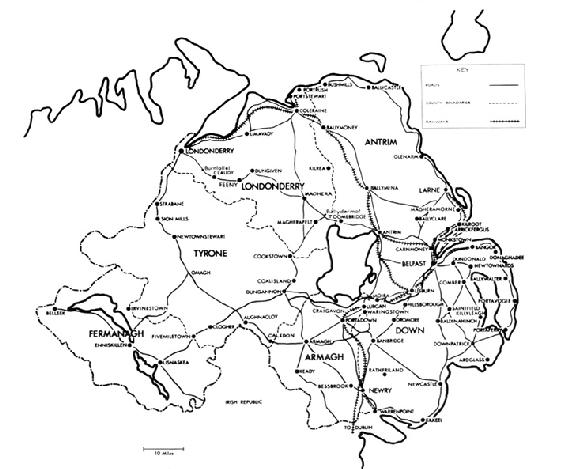

MAPS

NORTHERN IRELAND

(Taken from the Cameron Commission report)

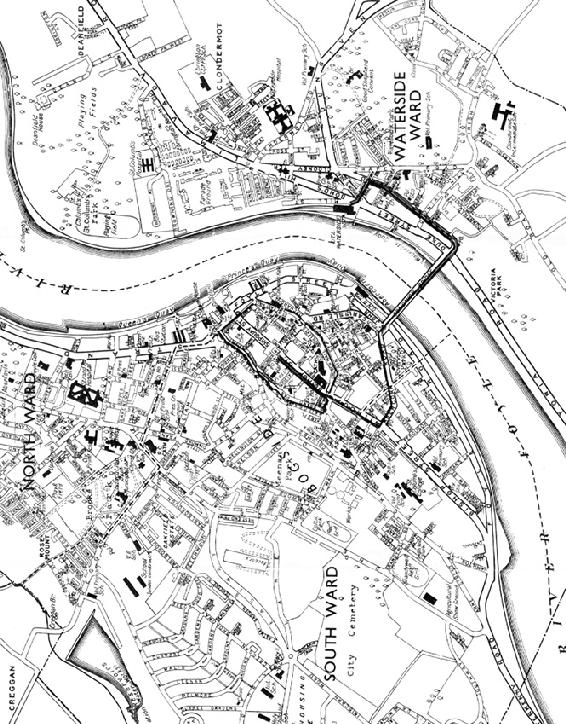

DERRY

(Taken from the Cameron Commission report)

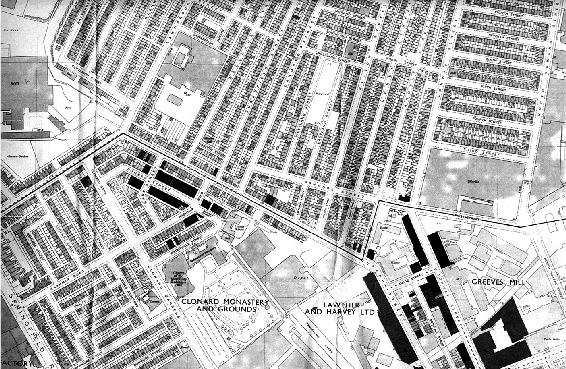

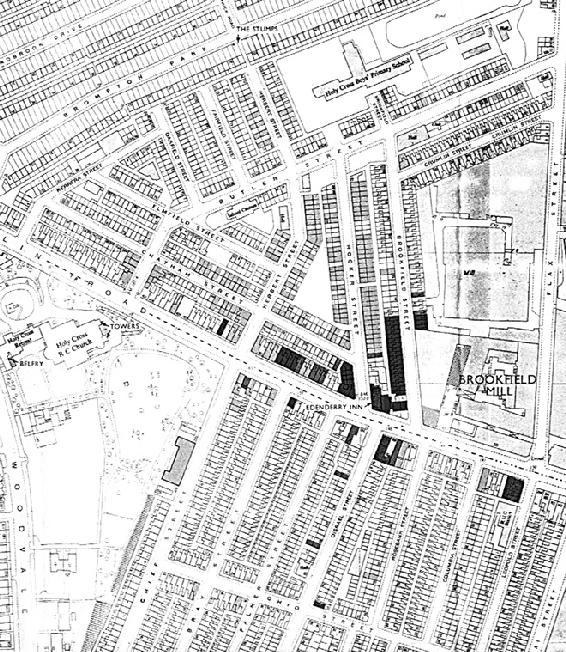

CONWAY AND CLONARD

(Taken from the Scarman Tribunal report)

ARDOYNE

(Taken from the Scarman Tribunal report)

DIVIS STREET

(Taken from the Scarman Tribunal report)

ABBREVIATIONS

CCDC Central Citizens Defence Committee

DCAC Derry Citizens Action Committee

DCDA Derry Citizens Defence Association

DI District Inspector

DUP Democratic Unionist Party

GPMG General Purpose Machine Gun

PD Peoples Democracy

GOC General Officer Commanding

IRA Irish Republican Army

NICRA Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association

RUC Royal Ulster Constabulary

RUCR Royal Ulster Constabulary Reserve

SDA Shankill Defence Association

SLR Self-loading Rifle

UCDC Ulster Constitution Defence Committee

UDA Ulster Defence Association

UPA Ulster Protestant Action

UPL Ulster Protestant League

UPV Ulster Protestant Volunteers

USC Ulster Special Constabulary

UUP Ulster Unionist Party

UVF Ulster Volunteer Force

EDITORIAL NOTE

As anyone familiar with the material covered in this book will know, there are problems in imposing any label on the two main communities that together comprise the large majority of Northern Irelands population. Many but not all Catholics are also nationalists in their political aspirations; most but not all Protestants are also unionists. However, there were then, and are now, substantial numbers of nationalists who are not devout Catholics, and many unionists for whom religion is peripheral to their attitude towards the constitutional question. The polarisation that has characterised the history of the state, and which became especially pronounced in the period discussed in the pages that follow, had little to do with religious differences, though at times (and particularly in the rhetoric of Ian Paisley and his followers) strident objections to Catholic religious teachings featured prominently. Mindful of these problems, I have usually opted to use the terms nationalist and unionist when describing these communities, though occasionally I also use Catholic and Protestant. In general I have used the terms republican and loyalist when describing groups or actions with some formal relationship to political and/or paramilitary organisations, or individuals who figure here as participants in specific organised actions.

My study makes extensive use of the Scarman Report of Tribunal of Inquiry: Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 , which is cited in footnotes as Scarman Report. I have also utilised the testimony of hundreds (mostly civilians) who submitted eyewitness accounts of events during the inquiry. These accounts are separate to the Scarman Report and have been cited in footnotes as originating in the Scarman Transcripts.

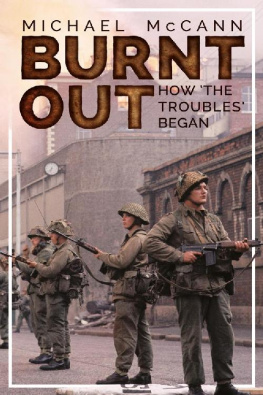

FOREWORD

TOMMY M C KEARNEY

The events of August 1969 in Derry and Belfast were among the most consequential to occur in the history of the troubled political entity that is Northern Ireland. During a forty-eight-hour period over 1415 August, eight civilians were shot dead four of them by the local police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary. Thousands more were made homeless as the result of a concerted incendiary assault led, on occasion, by members of the northern states police reserves, the Ulster Special Constabulary. The violence was directed against a practically defenceless nationalist population and was carried out by state agents acting in concert with their unofficial supporters. Such happenings would cause tremors in any society. In the North of Ireland, the consequences were profound and lasting.

In the first instance, the lethal nature of the violence effectively dashed hopes for a non-violent transformation of Northern-Irish society and largely sidelined the peaceful civil rights movement. Secondly, the scale of death and destruction meant that the British government was forced to commit its regular army to the region and, with direct intervention from London, Stormonts half century of absolute authority was brought to an end. A third consequence of those traumatic days was to bring another army into Belfast: a split in the republican movement caused by the bloodshed led directly to the formation of the Provisional IRA. The events also had a major impact south of the border, where the reverberations of August 1969 were felt all across the twenty-six-county state. The Dublin government performed a series of contortions as it sought to contain the anger of its citizens, then largely sympathetic to the plight of northern nationalists. Finally, the findings of the official Scarman investigation into August 1969 were skewed in order to exonerate the British state from complicity. Along with the Widgery Report into Bloody Sunday, Scarmans whitewash of state violence after the most traumatic episode in its short and violent history added further weight to the republican argument for breaking entirely with Britain.

Northern Ireland was created in 1920, partly to accommodate a pro-unionist community in the north-east of the island, but more significantly to guarantee the British Empire a physical presence in the strategically important island close to its west coast. A major weakness in the plan was the presence of a large minority in the newly created state that resented the arrangement from the beginning. From the foundation of the Northern Ireland state, this community of Irish nationalists was subjected to structural discrimination in employment, housing and cultural recognition. Crucially, the largest block of nationalists lived in virtual ghettoes in the states principal city, Belfast. The experience of previous pogroms within living recollection was seared into the folk memory of this tightly knit community.

Next page

www.mercierpress.ie

www.mercierpress.ie www.twitter.com/MercierBooks

www.twitter.com/MercierBooks www.facebook.com/mercier.press

www.facebook.com/mercier.press