MILESTONES IN MURDER

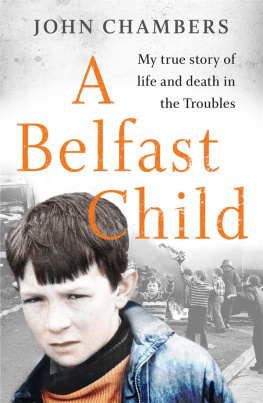

DEFINING MOMENTS IN ULSTERS TERROR WAR

Hugh Jordan

Contents

To the memory of my late parents,

Thomas John Jordan and Anne Cunningham Jordan.

Foreword

Writing about conflict while living in its midst, and not supporting the combatants, is a dangerous pursuit. Yet it is only through an understanding of the underlying causes of conflict that society can adequately address it. That understanding can only be achieved by writers prising open a window into the world of terror.

One has to get down there into the darkness to find out what it is about. From the first cave paintings about tribalism to the present day, humans have only been successful in dealing with internecine warfare when they have understood its causes. In so doing they have been able to avoid acting in a reflex manner that leaves them vulnerable.

Such understanding demands knowledge of the threat and those who represent it. The mainstream media rarely achieves the process of opening that window into communal strife or terrorism. It deals with the day-to-day events arising from violence and rarely peers behind the headlines to explain the seminal issues underpinning the thoughts, aspirations and actions of the participants to a conflict.

This is a book that will add to our knowledge of the Ireland conflict one that continues to simmer. Hugh Jordan has painstakingly investigated murders which individually and collectively portray a secret world of callousness and barbarism. It is a world few journalists choose to enter, but one that offers us clarity of perception about the players, whether they are mass murderers, terrorist agents, agents of the State or committed ideologues.

Hugh Jordan first discussed writing this book while we sat in the Windows on the World restaurant in the World Trade Centre in Manhattan over two years ago. I remember telling him that what he proposed to write was a book that would fill a gap in our knowledge. It would shed light on events seminal to a conflict we had both lived with for many years.

I reminded him that it was critical to his book that he understood the fact that history was more important to people in Northern Ireland than their counterparts in other areas of Europe. In many respects that was one of the underlying causes of conflict. Catholics learned Irish history not the history of Ireland. Protestants learned British history and not the history of Ireland. Both communities approached the conflict with a learned oral tradition of inherited prejudice. Anyone writing about conflict issues had to keep in mind those traditional thought processes in order to write with integrity and without embellishment about contemporary history.

I told him that when I wrote The Shankill Butchers and Dirty War I was castigated and threatened by people who felt I had not given myself to their agendas. Some warned that I had crossed the line in revealing aspects of the conflict that called into question their motives justifying the murder of innocents.

Like other journalists, I feared for my life. I kept a loaded shotgun by my bed and looked under my car each morning for fear it might be rigged with a bomb. I had been told by security sources that killers I had named by letters of the alphabet in The Shankill Butchers had met to discuss slitting my throat. Just as they had years earlier sat over drinks and planned the murder of innocents, they talked about my demise in a similar setting.

Mr A and Mr B were both alive at that time. Since then Mr B has died in a car accident but Mr A remains alive and well, living in west Belfast probably walking the same streets where he butchered his victims.

As Hugh Jordan has discovered, many of those who killed in the name of a cause or deity are no longer in prison. That is one of the peculiarities of conflict. Life never means life for murderers when the politics of expediency require political solutions.

I found it admirable that Hugh Jordan continued to write this book in the wake of the killing of his colleague, the journalist, Martin OHagan. Martins death illustrated the risks of writing about and living in the midst of conflict. Some observers commented that he was in the wrong place at the wrong time when he was shot dead. They failed to understand the nature of terrorism. By their standard so were the thousands of people in the World Trade Centre the day it was attacked.

On 11 September 2001, Martin OHagan phoned me in New York.

I just wanted to make sure you were okay, he said in his whimsical fashion.

I had been more concerned for his safety and had warned him on several occasions to be vigilant. When I had written God and the Gun he had set up interviews for me with people who shared the same prejudices as those who eventually murdered him. I wrote the following tribute to him:

To Martin OHagan

(Murdered in Ireland on 28 September 2001)

We lived with conflict, you and I,

wrapped in a war over space,

clothed in a history made by others.

We lifted stones and peered under them,

knowing a Bishop left vipers,

venomous and angry in ignorance.

A firestorm was in Manhattan

with another God in the mix,

while ours was in bullets waiting for you.

Hugh Jordan is a journalist familiar with the terrain and has brought to this book a serious journalistic study of killings that illustrate the murky and horrific nature of conflict.

Enough time has passed to enable a detailed investigation of episodes like the Malvern Street shooting, which occurred at a critical time in the troubled history of Northern Ireland. That event symbolised a period when major fissures began to appear within the Unionist monolith and led to a form of unionism that remains fractured to this day.

Malvern Street brought the gun back into politics as well as the cult of the gunman. It also involved a conspiracy that was conveniently swept under the carpet when the political tapestry of the province was dramatically changing.

Within the Catholic community, disillusionment with republicanism had given way to demands for change within the system. All the variables were in there as far as the IRA was concerned, from traditional nationalism moving towards socialism, and republicanism seeking a new definition and British civil rights. The events in Malvern Street in 1966 changed all of that. In many respects it was one of the critical elements in history that propelled both communities into a tribal conflict and decades of violence and suffering.

This is a book that people should read and learn from.

Martin Dillon

Epilogue

John Tierney, a former Mayor of Derry and now a member of the Legislative Assembly at Stormont, has spent a lifetime in politics. He is on the socialist wing of the SDLP and is a popular figure in his native city. Tierney and his family live in William Street on the edge of the Bogside. The street was the scene of many riots in the early days of the Troubles and it was there, on 19 April 1969, that RUC officers charged into Sammy Devenneys home before beating him unconscious. Mr Devenney died three months later as a result of the injuries he sustained that day. He was an entirely innocent victim and no one was ever charged in connection with his death. Many people in Northern Ireland believe the incident marked the start of what we have come to call the Troubles an era of violence which was to last more than a quarter of a century and claim nearly three and a half thousand lives.