Its a logical question. K2 is not Everest, not many have climbed it, and almost no one knows where it is. And besides all that, why me? Im a born and bred Yankee, worked most of my life reporting for Boston radio stations and magazines, and considered competing in ultra running trail races and the Ironman triathlon adventure enough. Not exactly your typical stepping-stones to the unspeakably dangerous and hypoxic world of 8,000-meter peaks that sit halfway around the world in Nepal, Tibet, and Pakistan. But thats exactly where I ended up.

My journey to K2, the second-highest mountain in the world, sitting weeks from civilization on the Pakistan-China border, began years earlier when I read Into Thin Air . Like millions of readers who learned the excruciating reality of high-altitude climbing through the story of Mount Everests deadliest storm in 1996, I suddenly found myself fascinated with that exotic and ruthless world at 8,000 meters, or 26,000 feet, an altitude above which life begins to die. Who were these strange souls who sought to enter that so-called Death Zone, and why did they revel in the literally mind-blowing experience of having millions of brain cells die in minutes?

I also became fascinated by the roles that women played in this high-altitude game of life and death and wondered how their experience differed from that of their male teammates. In my reading of Jon Krakauers brilliantly told story, I sensed a certain bias, an agenda, concerning the women on the mountain that year, particularly Sandy Hill Pittman, whose wealth and personality he spent a lot of ink chastising, as if being arrogant and rich somehow made her less of a climber. Further, while he seemed to point a finger of blame at Pittman for being a client who survived, he made heroes of the guides who died, and of one guide in particular who in my estimation made the worst errors of the day by climbing past his own turnaround time and pulling an exhausted client with him.

Why, I wondered, had Krakauer chosen to single out Pittman for vilification and not the men whose choices were, at the least, questionable, and did that bad air permeate the high-altitude experience for other women climbers?

So I kept digging, not knowing what I was looking for but somehow feeling I was missing the story. Then in 1998 I found it.

Chantal Mauduit just died on Dhaulagiri. Shes the last one, Charlotte Fox said.

We were sitting on Foxs back porch in Aspen, the afternoon summer sun hot on the terra-cotta tiles, sipping perfectly steeped ice tea and talking about her experience as a survivor of the 1996 disaster on Everest. She had been looking through a climbing magazine searching for an article I should read when she saw Mauduits obituary.

The last one what? I asked, embarrassed to be so obviously clueless.

The last woman who made it off K2 alive. She just died on Dhaulagiri in Nepal, Charlotte said, pausing to look at me to see if I had made the connection. K2, the mountain? Now all of the five women whove climbed it are dead.

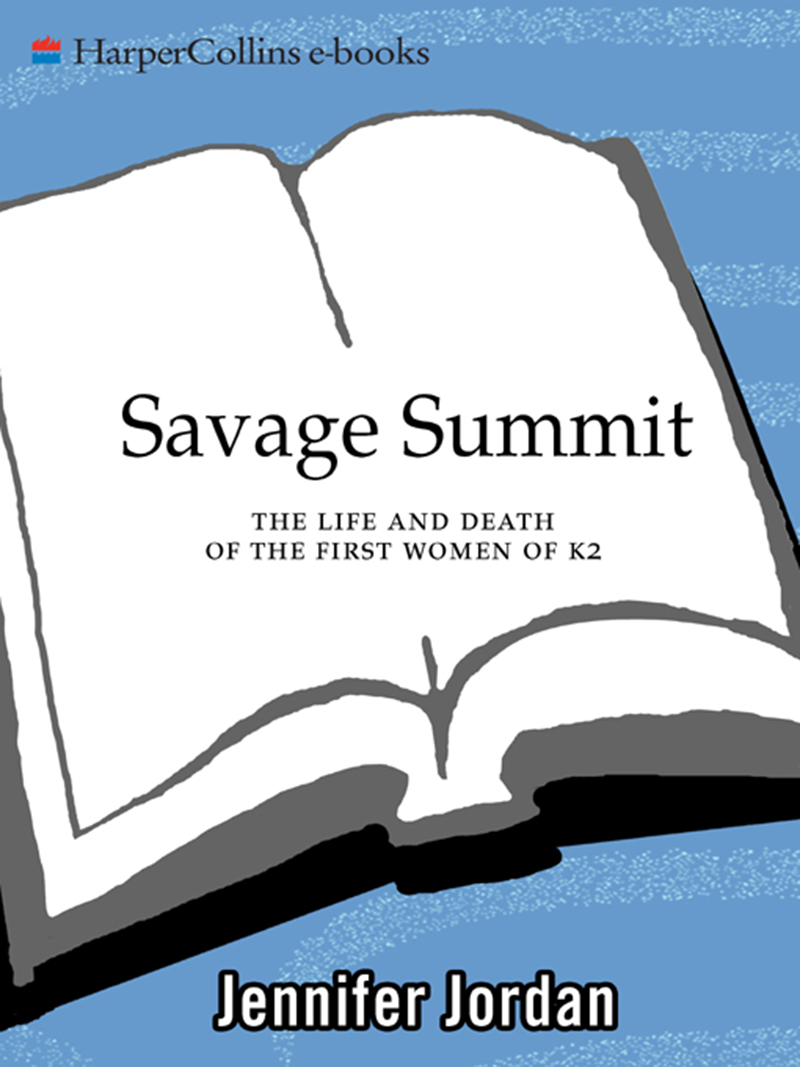

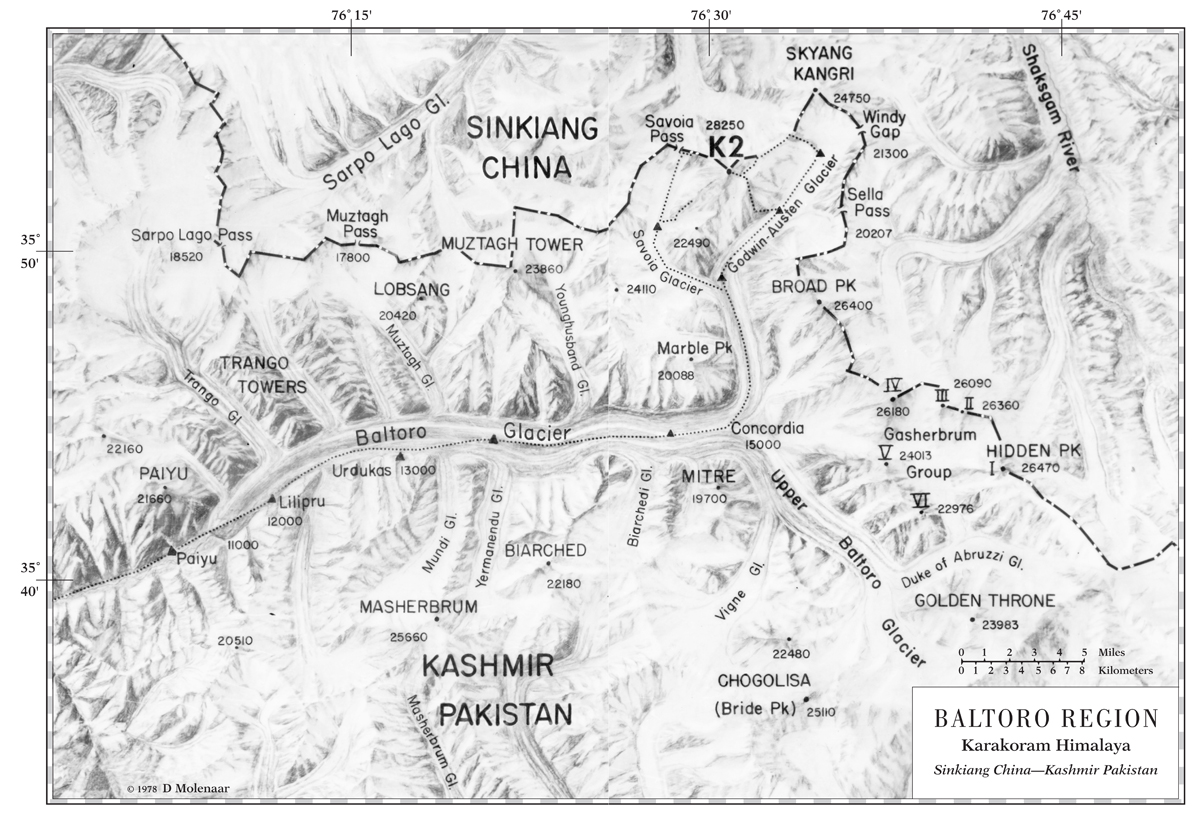

I didnt know who Mauduit was, or even where this K2 was, but I knew my mind and soul had had a sea change. My questions veered from women mountaineers in general to the women of K2. Why had so few women climbed it? Who were they? And most crucially, how could none of them have survived?

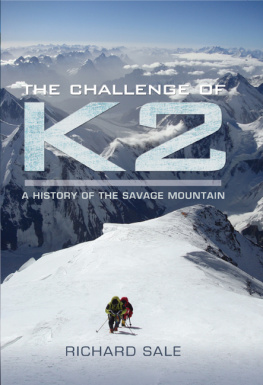

Soon I would learn that K2, at 28,268 feet (8,616 meters), is second out of the fourteen peaks in the world that rise above 8,000 meters, the height against which all other mountains are measured. Everest is, of course, first, but even though eight climbers had died there that one day in 1996, it seemed that toll was nothing compared to K2s track record. By the end of the 2003 climbing season, nearly 2,000 had climbed Everest, but fewer than 200 had climbed K2 in the same period. While Everest had suffered 180 deaths, K2 had seen 539.4 percent versus nearly 27 percent. Between K2s unrelenting 45-to 65-degree slopes, brutal weather, and general lack of high-altitude porters to carry oxygen and heavy loads high on the mountain, it suffered few fools and almost no clients. It simply didnt have the infrastructure for such hubris. As a result, it tended to attract the best climbers, and that made its death rate all the more remarkable. I had thought Everest was dangerous, but I was learning a whole new definition for the word lethal .

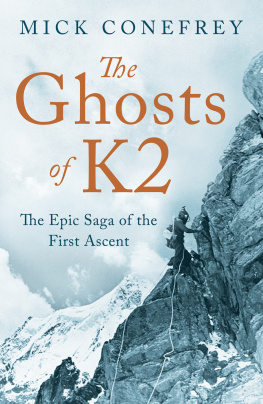

An early climber took one look at the far-off pyramid and declared it an unconquerable mountain of all rock and ice and storm and abyss. In 1953 it was dubbed the Savage Mountain by a team of young American climbers after one of their friends perished high on the mountain, and its continued to earn the distinction. At the beginning of the 2004 climbing season, nearly a half-century since an Italian team first made the summit in 1954, only five women had reached its summit (compared to ninety female ascents of Everest). Three of them died on their descent, and the two who made it off alive died shortly thereafter while climbing other 8,000-meter peaks. And in 1998 Mauduit became the last.

In the few years following that sunny Aspen afternoon, my research continued, and I came to know K2 as I knew few things in life. Over time I felt a love and tenderness for the five women who climbed it that journalists often gain for their research subjects. I learned that the first woman to climb K2 in 1986 remains unsurpassed with a climbing record of summiting eightperhaps nine8,000-meter peaks. I read that before another woman of K2 left Base Camp for her fatal summit bid, she had answered letters to her two young children eager for their mummy to return home couldnt she come home now ? I had spoken to another womans brother and learned that his younger sister had a love for life that often made her jump without looking for a safety net, a carefreeand some charged carelessjoie de vivre that defined her life. And I had learned that another woman of K2 had already seen six deaths on the mountain by the time she made her summit bid during the mountains deadliest climbing season in 1986. Her death would be among the years staggering toll of thirteen.

Who were these pioneering climbers, and why did they choose a life on the edge of death? Why did they die, and why did one mountain claim so many of them? How did they make the decision to leave family, husband, and children to venture into the worlds highest and most deadly playground? Did their gender have a hand in their deaths? And while the mountain may not have cared that they were women, were there other forces at work that did?

Grim and gruesome, these questions haunted me, and I wanted to learn more than books and memoirs could provide. Plus, the books and memoirs were mostly about men; women mountaineers seemed to be a footnote in climbing history. I knew they deserved their own book and thought I might as well be the person to write it. And even though the very thought of it terrified me, I knew I had to travel to Pakistan and see the mountain for myself.