FOR MY MOM

FOR MY MOM

CONTENTS

MARCHING

HOME

HOME

The living remaind and sufferd, the mother sufferd,

And the wife and the child and the musing comrade sufferd,

And the armies that remaind sufferd.

WALT WHITMAN,WHEN LILACS LAST IN THE DOORYARD BLOOMD

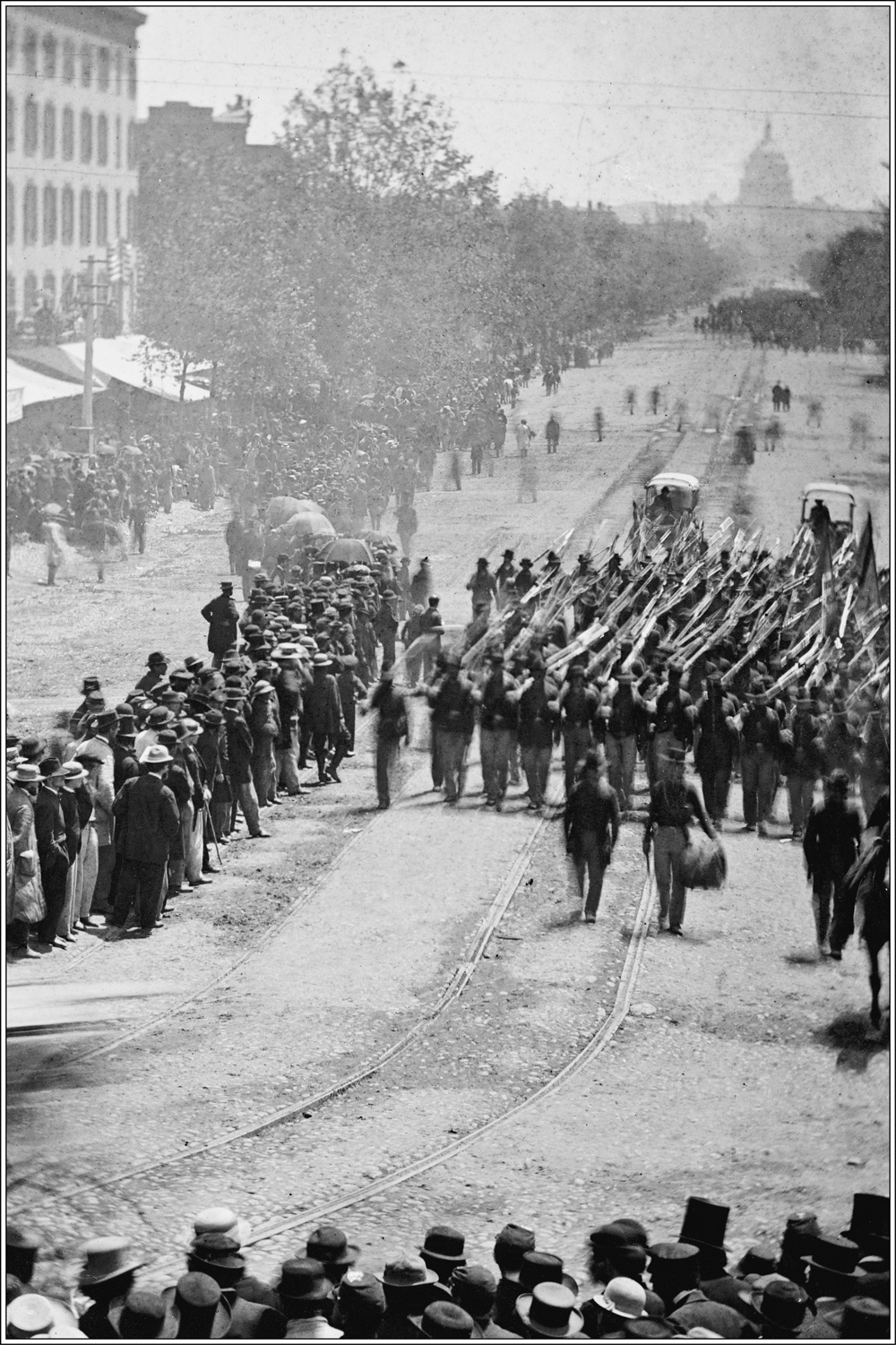

O N A HUMID July afternoon in 1913, a knot of Union veterans gathered near the spot where the low stone fence that rambled down Gettysburgs Cemetery Ridge pointed sharply east. Here, a half century before, the men of the Union army had repulsed nine stubborn brigades of gray-clad troops during the cataclysmic battles final act. Now, the bewhiskered men who had worn the blue waited for their enemy once more, supporting their wobbly, seventy-year old frames with gold-tipped hickory canes. The bronze Grand Army of the Republic badges proudly affixed to their lapels (they were cast from melted rebel cannon tubes) glinted as they caught the blistering sun of a Pennsylvania summer.

From just behind the stone wall, the Union veterans watched as the ex-Confederates crested the ridge. The passing of five decades had audibly diminished the ferocity of the old rebel yell, now just a coarse snarl. When the southerners reached the wall, the blue-coated men extended their wrinkled hands and doffed their campaign hats in a gesture of conciliation. With only blissful memories of the war, Union veterans absolved their former enemies and basked in the glow of a nation reunited. Later that evening, huddled around the sparks of a summer campfire, Lincolns hale troops swapped nostalgic tales of the old army days. As they puffed on pungent cigars, wreaths of white smoke curling into the air, it was difficultindeed, it was nearly impossibleto imagine that these jolly old men had shouldered muskets in a bloody civil war.

Americans are very familiar with romanticized scenes like this one, mounted in dusty old scrapbooks and captured on dozens of creaky newsreels. For generations, the presumption has been that the survivors of the Union armies beat a hasty retreat from the Civil War; that victory, unlike defeat, was essentially painless; and that time mended, like most things, the wars most horrible injuries. Popular notions persist that Union veterans returned to northern society awed, not beguiled, by the past. To be sure, many scholars have enthusiastically embraced historian Gerald F. Lindermans contention that Union soldiers paid as little heed as possible to the memories of war. According to Linderman, Union veterans permitted their martial past to simply fade away. They hibernated for decades after the war, only to reemerge in the late nineteenth century as nostalgic heroescherished heirlooms who willingly relinquished to their former enemies the wars meaning and legacy. Working from this premise, many observers have derided Union veterans as little more than effete old men who, after returning home and putting their hands to the plow, abandoned the fledgling promise of a new birth of freedom. One leading historian writes that by the 1890s, it was easy for Northern veterans to accept Southern claims that the war was really about arcane constitutional issues.

Indeed, despite all that has been written about the American Civil War, Union veterans remain eccentric caricatures lurking in the unwarranted shadows of historical obscurityas distant and unfamiliar to us as they were to those who lived in postCivil War America. Although a few historians have trailed the blue-coated armies home from Appomattox (most often by analyzing their fraternal rituals, their infamous pension lobbying, and their reunions, parades, and monuments), none have penetrated the most intimate human details of their lives.

Much of what we knowor think we knowabout Union veterans is informed by a sprawling literature on common soldiers. For generations, historians have revered Billy Yank, marveling at his uncommon sense of duty, his fearsome patriotism, and his principled devotion to the Union cause. Historian Chandra Manning has even suggested that the blue-coated armies were abolitionized by their experiences in battle. Encountering firsthand the cruel landscape of slavery, she insists, helped to sustain the fighting spirit of the rank and fileeven the resolve of those troops billeted in the sun-baked Virginia trenches of the wars final year. Esteeming the men who, with clenched jaw and burnished bayonet, triumphed over their rebel enemies, historians have supposed that the Union soldier was undoubtedly prepared for the peace. Consummate citizen-soldiers steeped in the classical republicanism of their fathers and grandfatherstaught to be upright, virtuous, and self-sacrificingthey returned to their homes demanding no reward.

Yet yellowed veterans newspapers, soldiers home records, disability pension files, and personal manuscripts chillingly demonstrate that even victory had a pricethat the terror of this unprecedented war long outlived the stacking of arms at Appomattox. As the West Point military scientist Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman has argued so persuasively, abandoning the precepts of peace for the rigors of warlearning how to kill and maimis psychologically demanding even for soldiers who emerge from battle victorious and unscathed. Afflicted with guilt, sorrow, and purposelessness, Union soldiers considered homecoming a task as onerous and demanding as any military campaign. Billy Yank often stumbled home after guzzling gallons of rum in dodgy grogshops. Many thousands returned north hopelessly addicted to the laudanum they had first sampled in the Civil War field hospital. Especially for those sporting empty sleeves or staggering along with irksome and ill-fitting wooden legs, joblessness, vagrancy, and penury loomed. Vivid nightmares of the picket post and the prison pen mocked any proclamation of peaceno matter how fiercely coveted. And, worst of all, the contemptuous sneers of northern civilians, combined as they were with mounting evidence that the southern rebellion was not yet snuffed out, urged these men to ask what their war had achieved after all. Postwar society could reach no compromise about howor even ifthe massive human costs of the war should be handled, and the federal government proved both ideologically and infrastructurally ill equipped to mitigate the challenges of homecoming. The stage was set for the veterans decades-long struggle to ensure that the scope and significance of their sacrifices would not be forgotten.

After the shock of Shiloh, the carnage of Antietam, and the horrors of the Wilderness, hundreds of thousands of ordinary men would never be the same again. They peopled a living republic of suffering. The twinge of a phantom limb, the decades-old gunshot wound that wept pus, and the gaunt faces of Andersonville survivors ensured that the wars costs could not be counted in crowded cemeteries alone. Union veterans endured the tragedy of the American Civil War until they, too, answered the final roll call. Suspended between the dead and the living, the rest of their days were disturbed by memories of the war. The dead come back and live with us, Oliver Wendell Holmes once declared. I see them now, more than I can number, as once I saw them on earth.

FOR MY MOM

FOR MY MOM

HOME

HOME