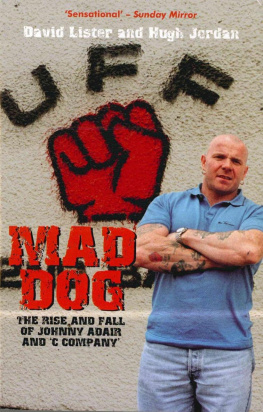

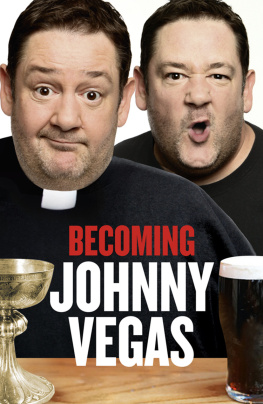

W hen asked by a journalist in the mid-1990s if he had ever had a Catholic in his car, Johnny Adair replied only dead ones. This was the first time I had ever heard of the man.

While shocking, this throwaway comment seemed to fit the image that most outsiders held (and still hold) of the Loyalist paramilitary vicious, nakedly sectarian, and, as one commentator argued, having all the political nous of a rottweiler. In fact, so typical and expected was this caricature for many, that little serious attention has ever been paid to the remarkable story of Northern Irelands once most powerful paramilitary movement, the Ulster Defence Association, or UDA, and those within it.

The UDAs main objective was to uphold Northern Irelands place within the United Kingdom. Until the eventual proscription of the pro-State movement by the British Government in 1992, the UDA remained a legal organisation using a series of cover names, such as the Ulster Freedom Fighters and Ulster Defence Force.

Because of the UDAs eventual descent into criminal activity, collusion with the rogue members of the security services in Northern Ireland and other various sinister events, it is easy to dismiss the UDA as never having had genuine political aspirations. Consequently, for years Loyalism, in all its forms, has gone largely unexamined, and this is why its significance continues to remain poorly understood.

In fact, it seems unbelievable even now that the UDA was once a formidable power that could command extensive social and political influence, yet in the early 1970s, the then 40,000-strong movement brought Northern Ireland to a virtual standstill by organising a general strike through the Ulster Workers Council (led by several senior UDA members). The UDAs objective had been to bring about several reformist measures in Ulster, notably the abolition of the Northern Ireland Executive and greater political representation at Westminster.

Yet, one decade later, and following the assassination in 1987 of arguably its most effective and strategic leader, John McMichael, the UDAs decline was set firmly in motion. By 1989, the movement was in complete disarray, and the security services in Northern Ireland had finally succeeded in virtually paralysing the movement.

Ironically, it was a major journalistic investigation by Roger Cook into the movements racketeering and extortion activities that combined with other events to ultimately lead to the UDAs internal reshuffle. There was a change of leadership and revitalisation with younger, fresh recruits who would each play their part in the UDAs new attempts to rearm itself from local, national and international sources. With the UDA energised, the movement returned as a dangerous force in the early 1990s, with Loyalist terror groups surpassing even the Provisional

IRA in assassinations, murders and casualties. In 1994, less than two months after the Provisional IRA declared its complete cessation of military operations, the UDA and sister movement the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) called their own ceasefires. For the first time the residents of Northern Ireland were given the hope of peace whilst the contending sides of the conflict engaged in dialogue rather than fighting with each other and the British government.

While much of the commentary surrounding the ceasefire period at the time might be characterized as both nave and premature, there were some overlooked developments within Loyalism that remain poorly understood.

The Loyalist position was that much of the political change in Northern Ireland seemed to have been at their expense (at least until the recent surprising resurgence of Ian Paisleys DUP). Loyalist marginalisation had been a deliberate policy of the then leading Nationalist movement, the Social, Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) that sought to go directly to the Irish or British government motivated by a concern to limit and perhaps abolish the historical Unionist veto.

However, for the first time in many years, political initiatives after the ceasefire offered (and even guaranteed) the Loyalist community a voice in the political process and the future shape of Northern Ireland. That the Loyalist paramilitaries enthusiastically participated and remained in this process despite the collapse of the PIRA ceasefire is worthy to note. And while the process would go on to expose the rivalries between the paramilitary and constitutional Loyalist political parties, by at least recognising the voice of Unionism, the ceasefire discussions guaranteed an outcome of compromise rather than a complete victory.

Of course, in the days immediately after the ceasefire, celebrations in Northern Ireland did not suggest a popular recognition of any impending compromise (indeed, 17 months later, the ceasefire would break down amid acrimonious accusations of bad faith and other issues). But on 1 September, 1994, celebrations in Republican areas had a distinctly triumphalist quality and there was a popular sense that the ceasefire represented a step towards the establishment of a united Ireland.

As the process developed, however, so too did it become clear that Unionism, far from being marginalised was being brought to centre stage. Juxtaposed against this development, the ruling Conservative Partys weaknesses forced a greater dependence on the Unionist vote in Parliament, further strengthening the Unionists bargaining position.

Just over one year into the ceasefire, the collapse of which would be heralded by a massive Provisional IRA bomb in London, former Northern Ireland Secretary of State Mo Mowlam took the unprecedented (and risky) step of acknowledging the critical role of the prisoners in supporting the peace initiative when she visited the notorious Maze Prison in Belfast. Among those she met was Johnny Mad Dog Adair.

Jailed in 1995 for membership of the UDAs Ulster Freedom Fighters and for directing terrorism, Adair was nothing less than an icon. Feared, hated and reviled in some quarters, idolised and revered in others, Adair remains both an enigmatic and divisive figure. His story makes for reading that is as uncomfortable and unsettling as it is breathtaking in its audacity set against a chaotic backdrop of some of the worst atrocities of the Northern Irish troubles.

Several dozen Catholics were murdered, often in horrendous circumstances, by the unit that Adair commanded. C Company, and indeed the UDA overall, never successfully shook off the image of being blatantly sectarian. The stunning discovery that members of the security services fed intelligence to the UDA only demonised it as typical of Northern Irelands dirty war. Convinced by Mowlam of the merits of supporting political representatives, Adair was released four years into a 16-year sentence.

Ironically, the 1994 ceasefire also served as the catalyst for years of savage internecine feuding which ripped apart the remains of the once formidable Loyalist groups. Despite positive early signs, the UDAs representatives failed to establish an effective political presence in the wake of the ceasefire. The UDA, in Adairs words, imploded. With no IRA to fight, the movement would turn inward, unclear of its purpose and place within a rapidly changing political scene in Northern Ireland.

Since 2000 the UDA has degenerated into movement torn apart by territorial jealousies, competition over the proceeds of organised crime and continued differences over political aspirations and loyalties. Jealousies, bitter rivalries and a series of personality clashes have conspired to see the UDA kick Adair out of the organisation in 2002 for his efforts to link the UDA with the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF). Some viewed Adairs work as an attempt to consolidate his power and influence over the combined Loyalist command.

With Adair in and out of prison during this time, the UDA began its housekeeping in earnest and the remnants of once mighty C Company were systematically dismantled. Adair and his family would eventually take temporary refuge, first in England, then Scotland. Since then, all who have pledged allegiance to him have been left alienated and at risk.