To my wife and children, the great loves of my life

Livin the dream...

Contents

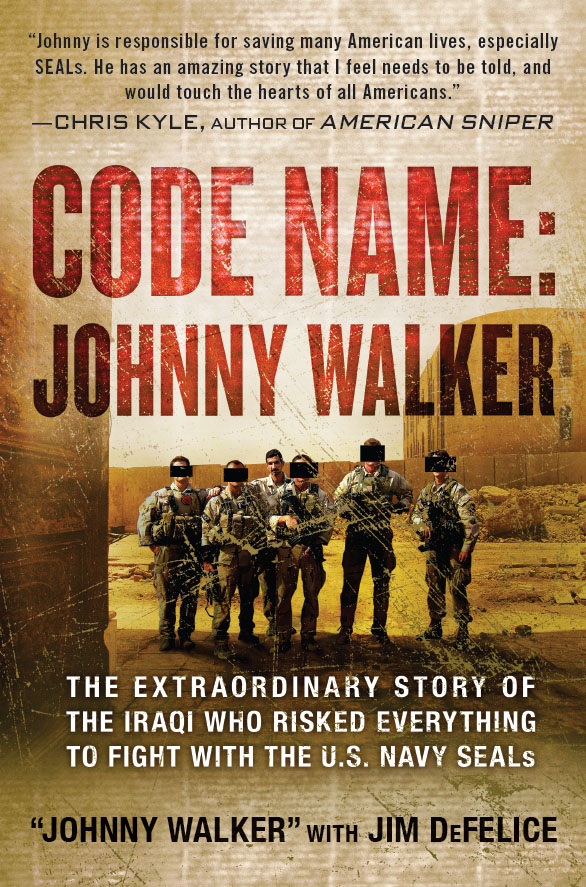

THE EXTRAORDINARY STORY

OF THE IRAQI WHO RISKED

EVERYTHING TO FIGHT WITH

THE U.S. NAVY SEALs

Though many people know me as Johnny Walker, it is not my real name. Its actually a nickname the SEALs gave me while I served with them in Iraq.

In order to protect my family, both here and in Iraq, I have decided to use only that name. I have also found it necessary to omit and generally obscure the identities of those closest to me in Iraq, along with other identifying characteristics, so that their lives will not be endangered. I have done the same for security reasons involving some of the missions I undertook with American and Iraqi forces, as well as changed or otherwise used my own nicknames for all former and active-duty SEALs important to the story.

The incidents recounted here are from my own memory. Admittedly, time blurs much, but I and my cowriter have tried to corroborate everything possible. The dialogue has been reconstructed and in many cases translated from Arabic; it is not meant to be verbatim but rather representative of what was said and what happened at the time.

INDOMITABLE SPIRIT

Johnnys ingenuity, indomitable spirit, and utter fearlessness not only protected the lives of many SEALs, but also saved the lives of countless innocent Iraqis. He is a true hero to all of us.

Some of my most memorable moments in Iraq took place while hanging out with Johnny and the Iraqi commandos, marveling at Johnnys ability to unite Shias, Sunnis, and Kurds as we discussed challenging topics like religion and ethnic conflict. This continues to be Johnnys contributionhis monklike, thoughtful appreciation of how life works and how to lead it well.

Seeing Johnny and his family living safely in the United States, embracing life as patriotic Americans, is something I will cherish forever.

CAPTAIN X, SEAL TEAM COMMANDING OFFICER

GOOD FROM EVIL

The war in Iraq: No issue has divided our country more since Vietnam. The soldiers, sailors, airmen, Marines, and their families have paid an incredibly high psychological and physical toll. The same can be said for the Iraqis. Economists decry the amount of money spent with little return on investment. Parents lost children. Husbands and wives lost spouses. Children lost parents. Warriors lost brothers and sisters. The question I have been asked many times, by others and even myself, is: Was it worth it?

While deployed to Iraq, that answer changed many times. When a suicide bomber detonated himself at Checkpoint 12 in the Green Zone, killing a young National Guardsman, the answer was no. But when we decimated an al-Qaeda cell responsible for training and equipping suicide bombers, then it was absolutely yes.

When an IED detonated and killed not only American soldiers but also a mother and her children, it was a resounding no. But when our snipers killed a mujahideen fighter placing an IED, it was a resounding yes.

Of course, without the war, or without any war for that matter, those situations would never present themselves. War is worth it only for those who dont have to fight it or live with the consequences. But make no mistake, there are some horrific people in the world who will stop at nothing to impose their twisted vision on all those who wont fight or fight back. They need to be dealt with viciously, yet surgically.

I have come to realize lately that perhaps the better question to ask is whether any good came from the war. I will allow the historians and politicians to debate endlessly on the strategic impact. I, like every other person who fought there, can only answer on the personal level.

My answer is yes.

For me, the little things made all the difference. Conducting a direct-action mission in al-Dora to capture an al-Qaeda member may have had little strategic significance. But it meant that the California National Guardsmen and -women who controlled that jewel of a neighborhood would not get hit with an IED for a week.

Lives were saved; others found a moment of respite from horror.

There were many similar tactical victories that did much good. For me, the most surreal and decisive came during the trial of Saddam Hussein. At the time, I had two of our new interpreters living in my room. We had a satellite television hookup, and it quickly became the hangout for all the linguists, better known to us as terps. The day the verdict was to be read, representatives from every demographic in Iraq crowded into my room. One was a Shia who had fled to the States after the first Iraq war when he and the other Shia were systematically wiped out following their unsuccessful uprising. Another was a Kurd who had escaped with his family to America following the extermination of his village from a gas attack by Saddam; he and his wife had carried their children to safety by trekking fifty kilometers in the winter to the Turkish border. One gentleman was a Christian who had had the misfortune of taking care of Uday and QusaySaddams sonswhen they were children; hed left the country after the first Gulf war and moved to Pasadena. And, of course, Johnny Walker, still an Iraqi citizen, was there.

It is impossible for me to describe the emotion and elation when the verdict of guilty came across the TV. They were all dancing, hugging, shouting in celebration. I could literally feel the yoke of tyranny being lifted off their collective shoulders. It was good.

For all of them except Johnny, it was closure. They could do their time in Iraq and return to the new lives they had made for themselves in America.

Not Johnny.

This was when the gravity of the situation really hit me. Johnny Walker would have to live with the aftermath.

Shortly thereafter, I hit up Johnny to see if he wanted us to work on a path to citizenship for him and his family. He responded, Brother, this is my country. I am going to see it through.

I kind of figured he would say that, but I could tell that Id blown oxygen on a flame that was lit in the room on the day of the verdict.

Over the course of the next month, I hoped in vain that Johnny would come and take me up on the offer. Finally, in October 2005, the day came for me to depart Iraq and head home. It goes without question that I could not wait to see my family. But I had a huge pit in my stomach. I knew the danger Johnny was in. (He understates it in this book).

When we said good-bye, I feared he wouldnt survive the war. He risked so much to help us and there was no way to repay him if the U.S. pulled out of Iraq. It felt wrong not having him come to the States, but I respected his dedication to his country. Still, upon my return to the safety of my country and the love of my family, I felt a lingering guilt.

That changed months later when I got the call from the CO of SEAL Team 1 telling me that things had gotten too bad for Johnny and family and he wanted to come to the States. The concern and guilt now had an outlet. Over the next three and a half years, countless SEALs played a part in moving the painstakingly slow immigration process forward. It is a testament to Johnnys incredible character when I look at the time and energy put into this endeavor by so many warriors.

I must pause here and thank George, the lawyer, for all his help. He managed the process with incredible patience and a tireless work ethic. Without his benevolence and skill, Johnnys story may not have been told.

On July 8, 2009, I was out in the desert conducting training prior to a return trip to Iraq. I knew Johnny and family were inbound to San Diego, but until I had confirmation I couldnt be at ease. Finally I get a text from George: He made it. They are all here.