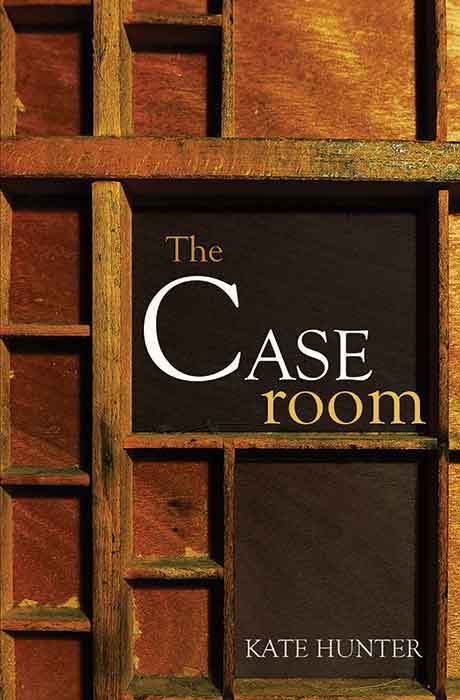

The Caseroom

Kate Hunter

Kate Hunter 2017

The author asserts the moral right to be identified

as the author of the work in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988

All characters appearing in this work are fictitious.

Any resemblance to real persons, living or dead,

is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of Fledgling Press Ltd,

Cover illustration: Ciara OConnor

Published by:

Fledgling Press Ltd,

First published 2017

www.fledglingpress.co.uk

Print ISBN 9781905916221

eBook ISBN 9781905916917

Acknowledgements

A big thank-you to Cathy, Becca and Adrian for reading drafts and for their suggestions and encouragement. Loving thanks to Phil for, well, being Phil, and to Jane for being Jane. And special thanks to my son Justyn and big sisters, Hazel and Maureen, for their quiet faith in me.

Thanks to Professor Sin Reynolds for climbing to her attic to retrieve her research files; to the staff of the National Library of Scotland and The British Library; to New Writing South for awarding me a free read with The Literary Consultancy (TLC); to the TLC and Lesley McDowell for their encouragement; and to Clare and Paul of Fledgling Press for truly appreciating my work. Thanks also to Ciara OConnor of ECA for her cover illustration and Graeme Clarke for his graphic design.

Part I A frock at the frame: 189196

1891: Into the caseroom

W akening, s he raised her head and peered through darkness to where dirty yellow light from a streetlamp smudged window panes, sink and stove. Going on six by her reckoning. Waiting for bells to strike the hour, she shut her eyes and opened her ears to rhythmic snuffles from her mother, dead to the world by her side; to creak of springs as her sister shifted in her bed in the corner; from ben the bedroom, a gasp as her father trawled for breath; a loud snort, then silence. Not a cheep from her brothers.

Hands clasped to her breast as though in prayer, she clamped elbows to ribs to contain a tingle in her veins that put her in mind of herself as a bairn on gala day, except that that bairns blood would not have had this peppering of fear in it. So how come it was there? What this day held in store gave true cause for excitement, aye, for apprehension, aye. But fear? What was there to be feart of? In answer, her brother Rabs face, white-lipped and seething, came to mind. Last night when, silenced by a sharp word from their father, Rab had gritted his teeth, shed felt triumphant. But even as shed felt it shed had an inkling that such a triumph would not withstand the light of day.

Shed not lain long before metal rang on stone in a nearby street. Keeping an ear pinned to the bedroom, she listened to hooves clip-clop closer. Rattle of milk churns. Must be gone six. She slipped from under blankets and squatted at the chanty, beam end pressed to cold rim to muffle the tinkle, a common enough sound of a night but one that at this hour, with day nearing, might act like a hooter to rouse folk. In two ticks she was dressed in clothes left ready over the back of a chair: drawers, light summer vest, stockings, faded grey and black striped dress, fresh-laundered, navy smock. Boots? No. She set them down by the door ready till shed got porridge and dinner pieces made.

The strike of a match, hiss of gas, scrape of pot sounded deafening to her, but no-one roused. Set to soak overnight, the oatmeal porridge was ready by the time shed sliced bread, spread lard, smeared on potted haugh and wrapped six pieces. After putting a package in her smock pocket, she ate a few spoonfuls of porridge straight from the pot, blowing to cool it, watching tenement windows across the street come to life as dawn light rinsed out dark.

Too early to leave yet, but she wanted to be off. Shed walk a long way round, stop at a bakers to buy a roll straight from the oven, sit on a step or crate to eat it. Though a trace of nights chill would be in the air, this September was mild as anything. She looked up. A wee strip of dulled silver sky above roofs was tinged with pink and blue. No sign of rain clouds.

First, though, the best bit, the bit shed been leaving till last. From a corner of a shelf she took down the setting stick and box of rules her father had presented to her. Used tools, aye, but, still, good tools. Last night shed held them in her lap to finger them, but Rabs glower had made her think better of loosening the screw on the stick to move the measure, opening the boxs neat clasp to take out the stack of wee brass rules. Studiously ignoring her brother, shed set her tools down safe with the hair clasp youd easily take for real tortoiseshell and her wooden pencil case with a diamond of ebony inlay, sleek and fine despite being chipped.

Thump. Tinkle. Thought of Rabs glower had her fumble and drop her rule box. She braced. At least it sounded as though the clasp had held. Holding her breath, she crouched to run a hand across the floor, ear cocked. A murmur. A groan. Was that a shuffle? Her father and brothers were rousing. That dark wedge by the chair leg? Aye. Sure enough, the clasp had held tight, the rules had not spilt and she had the box safe in her pocket.

Shed run fingers through her hair, given her plait a quick tuck and tidy and coiled it under her navy hat, was into her boots and had a hand on the doorknob when creaking floorboards made her freeze.

A hand clasped her shoulder.

Dont do it, Rab hissed in her ear.

Sensing a trace of pleading in his command, she hesitated.

Youre in the wrong, he growled.

No ahm not, she growled back, shoving his hand from her.

On the stair, she heard him come after. It was early yet for neighbours to be off to work, the stair was clear, and she was at the door, nearly out in the street, when he barged in front to block her way.

Youre set to bring shame on this family. On your father, on your brothers, on me.

Rabs doleful tone was nigh-on weighing her down with all this shame, but when he prodded his chest and squeaked on me the weight fell away and, close to laughter, Who do you think you are? came out of her mouth.

Rab grabbed her upper arms. His claws dug in. Me? Ahm a man at the frame, doing a mans work. And you? You mean to be a frock at the frame? Better youd never been born.

That took the breath out of her. She went limp. Shed felt spit land on her cheek and she needed to be rid of it. As she tugged to raise a hand she looked into Rabs eyes. Though he was six years her elder, he wasnt so many inches taller. Seeing as hed not stopped to put his specs on, his pale blue eyes looked frail, putting her in mind of a newborns opened for the first time. They had sleep in the corners and rapid blinks weakened their glare. Again, she nearly laughed, but before the laugh was out it was stifled by a yen to comfort him, to pat his arm and say, Itll be fine, Rab. Go back up and get your breakfast. Its made ready.

A clomp of boots had Rab keek over her shoulder. They were blocking the way of a neighbour off to work, and as Rab gave him a nervous smile and a clipped mornin, his grip on her loosened. Blood brought to the boil by that smile, that mornin, as if it was in the normal run of things for a brother to be bruising his sisters arms and telling her shed be better off unborn, she wrenched free, skirted round him and stomped off.