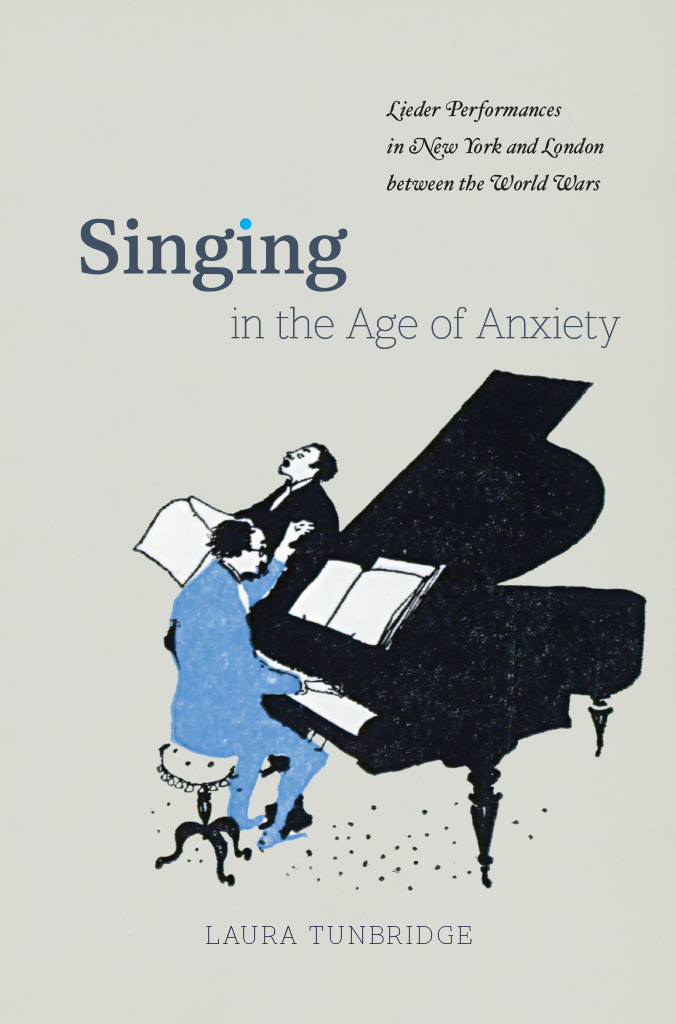

Singing in the Age of Anxiety

Singing in the Age of Anxiety

Lieder Performances in New York and London between the World Wars

Laura Tunbridge

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2018 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2018

Printed in the United States of America

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-56357-2 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-56360-2 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226563602.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tunbridge, Laura, 1974 author.

Title: Singing in the age of anxiety : lieder performances in New York and London between the World Wars / Laura Tunbridge.

Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017059451 | ISBN 9780226563572 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226563602 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: SingingNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. | SingingEnglandLondonHistory20th century. | Songs, GermanSocial aspects. | MusicSocial aspects. | MusicPerformanceHistory20th century. | World War, 19141918Influence.

Classification: LCC ML2811.8.N48 T76 2018 | DDC 782.421680943/097471dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017059451

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

In memory of David Tunbridge and Catherine Stewart

Contents

An Anxious Age

Three men and a woman sit in a bar on Third Avenue in New York City during the Second World War. Their thoughts and talk are interrupted now and again by the radio, compelling them to pay attention to a common world of great slaughter and much sorrow.adaptability of these songs and their singers enabled them not only to survive, but to stand as symbols of hope for what the sociologist Norbert Elias termed the civilizing process.

Anxiety and civilization run as dual themes throughout the following chapters, refracting some of the major preoccupations of the interwar period in Europe and the United States that pertain to lieder: nationalism and internationalism, and their ugly cousins xenophobia and racism; the status of high-culture and leisured society and aspirations to share it with and spare it from other classes; and the impact of this first media age on social activities, including live music making. His point is that older technologies continue to be used despite the historians emphasis on the new (his most often cited example is horses on battlefields alongside tanks). Along similar lines, I am writing not about new music, but about repertoire that was learned, sung, and listened to in regular concertsabout what constituted everyday concert life for members of a certain social class (and, occasionally, beyond them). I am also concerned with the ways in which new mediarecordings, radio, and sound filminteracted with live performance and vice versa, rather than treating them as separate activities. This book might still be taken as a narrative about canon formation. More than that, though, it illustrates the precarious fortunes of those canons. Lieder fell out of Anglo-American recitalists repertoire during the First World War, and it was not until after the Second that they came to be as respected as they are today. One of the main findings of this book is that, rather than reaching back to nineteenth-century practices, it was during the 1920s and 30s that the performance culture surrounding lieder with which we are now familiar came into being.

Singing in the Age of Anxiety grew out of my survey of the song cycle, from What was a paragraph or two became a project that offers insights not only about the Anglo-American reception of lieder, but also about musical life during the first half of the twentieth century. Within its generic, temporal, and geographic limits, this is a book about how musical performance can articulate identity, about the evolution of recording technologies and modes of listening, and about hierarchies of taste. The discussion is necessarily wide-ranging, and an introduction to its themes and sources, as well as the books structure, may be helpful before delving into its main chapters, which, while arranged in loosely chronological order, concentrate on particular topics: the reintroduction of German music and musicians to New York and London after the First World War; issues of language and listening practices raised by the presentation of lieder in concerts, recordings, radio broadcasts, and films; the social standing of classical song; and attitudes to German music and musicians from the 1930s until the aftermath of the Second World War.

Audens The Age of Anxiety, according to the literary scholar Edward Mendelson, ends with an almost instinctive wish for a shared community we can imagine but never achieve.

Writing in the 1920s, Norbert Elias was careful to distinguish between Kultur and Zivilisation. It was the purview of those people, Elias explained, whose national boundaries and national identity have for centuries been so fully established that they have ceased to be the subject of any particular discussion, peoples which have long expanded outside their borders and colonized beyond them: in other words, the British and French. Elias acknowledged that the function of the German concept of Kultur took on new life as the First World War raged, for the Allies fought in the name of civilization. It is a word that will recur throughout this book, in situations as diverse as explorations of hotel civilization to antifascist rhetoric, and with certain kinds of musicnot always those associated with Kulturbeing co-opted as symbols of civilization.

Other writers, from other countries, may have used slightly different terms from those chosen by Elias, but the polarity of national and supranational remained. Arts educators would attempt to harness the forces of broadcasting and the record industry to improve the taste of the general public; at the same time, as will be seen, there was a drive to protect certain music and modes of being from the hoi polloi.

Joseph Horowitz argues that the Great War shattered the concept of civilization as pursuant to truth and beauty; that the rhetoric of uplift that had accompanied classical music in Americas Gilded Age rang hollow, particularly after it was co-opted by European dictators for a very different type of cultural, communal catharsis. Although repertoire was co-opted to political ends, it was not only by dictators. The ability of music to forge communities, to raise morale, and to bolster propaganda during wartime was recognized by both sides. However, as this book demonstrates, the ways in which classical music was used, rhetorically and affectively, during the First and Second World Wars fundamentally contrasted. That said, there were historical continuities between and beyond the outbreak of hostilities. What constitutes between the wars, in other words, needs to be defined loosely. Both wars were cataclysmic, but while they may have accelerated some things and curtailed others, certain practices and people remained. In order to explain attitudes and activities after 1918, it is necessary to say something about what happened beforehand; in order to comprehend the import of 1945, its aftermath needs to be acknowledged (note that Audens

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).