Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Copyright 2022 by Matti Friedman

Hardcover edition published 2022

Signal and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisheror, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agencyis an infringement of the copyright law.

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by Spiegel & Grau LLC.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication data is available upon request.

ISBN9780771096266

Ebook ISBN9780771096273

All quotes from material by Leonard Cohen, published or unpublished, appear with the permission of the Leonard Cohen Family Trust and Old Ideas, LLC. All rights reserved.

Owing to limitations of space, photography acknowledgements appear on .

Cover and book design by Andrew Roberts

Cover art: Isaac Shokal

Published by Signal,

an imprint of McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited,

a Penguin Random House Company

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

a_prh_6.0_139631744_c0_r0

Welcome to these lines

There is a war on

But Ill try to make you comfortable

l. cohen

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Some of the men on the sand look up at the visitor with his guitar. Others look down at their dirty knees and boots. Cigarettes glow in the dark. The heat has broken and the desert is still for now. Theyve been fighting for fourteen days and no one knows how many days are left, or how many of them will be left when its over. There arent any generals or heroes here. Its just a small unit getting smaller. In the wastelands around them, thousands of Egyptians and Israelis are dead.

The visitor, dressed in khaki, is Leonard Cohen. This makes little sense to anyone at the outer extremity of the Sinai front in the Yom Kippur War of October 1973. Not long ago he was playing for a half million people at the Isle of Wight Festival, which was bigger than Woodstock. Here its a few dozen. None of the soldiers know how Leonard Cohen came to be here with them, or why.

Cohen is thirty-nine. Hes been brought low and thinks hes finished. News of his retirement has appeared in the music press. I just feel like I want to shut up. Just shut up, he told an interviewer. He might have come to this country and this war looking for some desperate way out of his dead end, a way to transcend everything and sing again. If thats what he was looking for, he seems to have found it, as well see. Five decades later, on Spotify and in synagogue, you can still hear the echo of this trip. Anyone reading these lines remembers the elderly gentleman grinning out from under a fedora at packed concert halls around the world, and knows that in 1973 his greatest acts are yet to come. But right now this isnt clear to him or to anyone else.

Cohen addresses the soldiers in solemn English. A reporter who is there describes the scene in a dispatch for a Hebrew music magazine. In the yellowing newsprint you can tell the reporter is a cynic. He mocks the star as the great pacifist come from abroad, a glorified tourist. A reader has the impression that the reporter doesnt want to be moved but is.

When the soldiers join Cohen for the chorus of So Long, Marianne, their voices are the only sound in the desert. He introduces the next number. This song is one that should be heard at home, in a warm room with a drink and a woman you love, he says. I hope you all find yourselves in that situation soon. He plays Suzanne. The men are quiet. They hear about a place that doesnt have blackened tanks and figures lying still in charred coveralls. Its a city by a river, a perfect body, tea and oranges all the way from China. Theyre listening to his music, writes the reporter, but who knows where their thoughts are wandering.

Sometimes an artist and an event interact to generate a spark far bigger than both: art that isnt a mere memorial to whatever inspired it, but an assertion of human creativity in the face of all inhuman events. It isnt necessary to know the convoluted course of Spains civil war to grasp Picassos Guernica. A listener can wonder at Beethovens Fifth Symphony, composed amid the Napoleonic Wars, without recognizing the bars of a French revolutionary song hidden in one of the movements. Its possible to appreciate the beauty of a shard of glass without knowing how the window looked before it was smashed, or what the moment of shattering was like. But it seems to me that if we can know, our understanding is enrichednot just our understanding of a momentous occurrence or of the personality of an artist, but of the nature of inspiration, and of arts supernatural ability to fly through years and places and lodge in distant minds, helping us rise beyond ourselves.

The moment, in this case, was a concert tour, maybe one of the greatest, certainly one of the strangest. The tour might have produced a celebrated rock documentary or live albumbut no one thought to film it and hardly any recordings survive. It happened in the midst of an Israeli war but isnt documented in the countrys military records. The account you just read is the only description of any of the concerts to appear in print at the time, and even that magazine, a local version of Rolling Stone, has been defunct for years. The tour has lived on as underground historyin word of mouth, in photographs snapped by soldiers, in notebooks filed in an office on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, in a box of papers in Hamilton, Ontario, and recorded between the lines of a few great songs. Reconstructing what happened has meant piecing together these scraps over many years.

While no detailed account has appeared before, and while this cultural moment is known even to Cohens fans as a footnote, if at all, its importance keeps growing in a curious way. Here in Israel, for example, before the anniversary of the war every fall, more and more articles appear in the press, as if the story must be told and retold each year. Some of the descriptions are repetitive or inaccurate. But all are genuine expressions of the fact that the memory of that terrible month, October 1973, has somehow become linked to the strange appearance of Leonard Cohen.

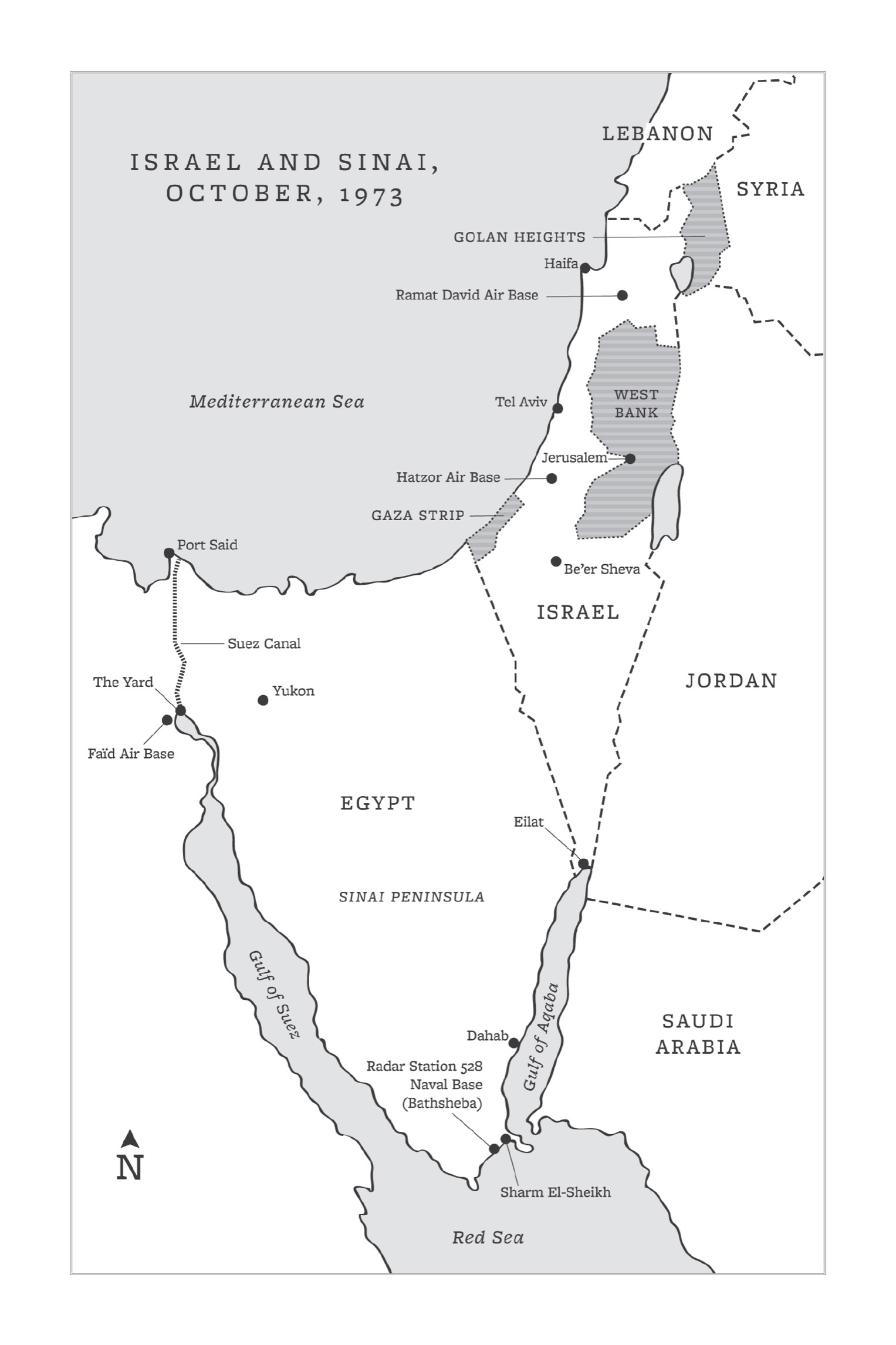

If Cohens tour is now part of the Yom Kippur War, the war itself is inseparable from a date in the Jewish calendar. The fighting began with a surprise attack by Syria and Egypt at two p.m. on the Day of Atonement, when Jewish tradition demands introspection and tells us that our fates are decided for the coming yearwho will die, and how. The symbolism here is so clumsy that it seems to beg an apology.

The wars timing has lent a kind of awful grandeur to the grim proceedings. In fact the war is sometimes called the War of Atonement, as if it were itself a penance for the pride and blindness that preceded it, for the failures of leadership that left Israeli soldiers exposed on October 6, 1973, when the Syrian army attacked through the basalt outcroppings of the Golan Heights and the Egyptians across the sand embankments of the Suez Canal. Israels judgment had been clouded by victory in the Six-Day War, six years earlier, and the country had allowed itself to sink into arrogance and complacency. The borders were defended by a handful of ill-fated infantrymen and tank crews.