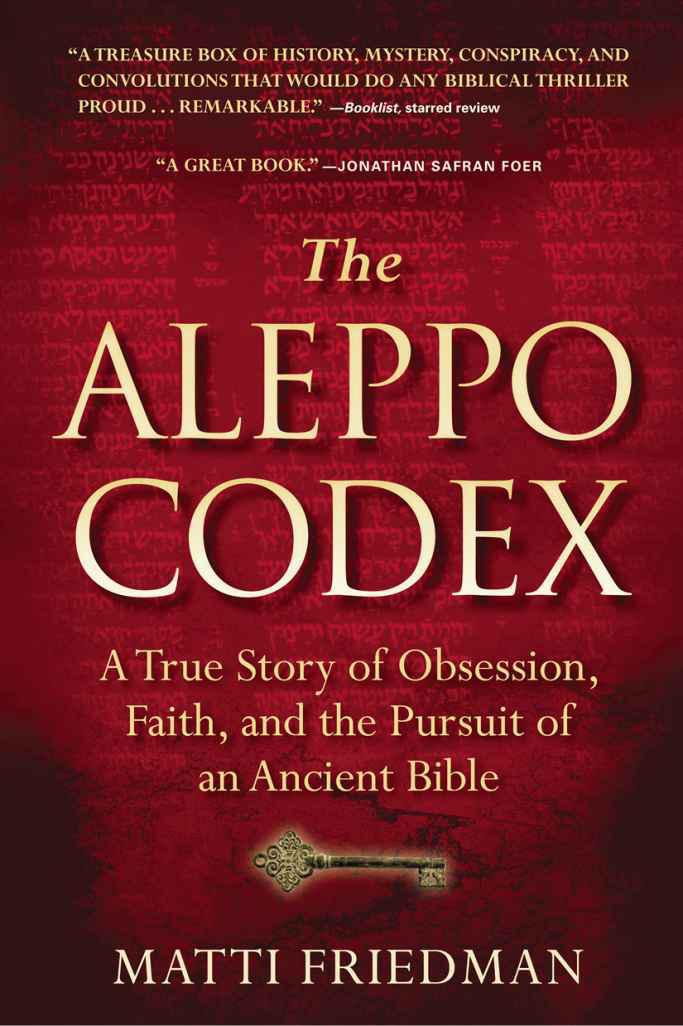

The Aleppo Codex

A True Story of Obsession, Faith, and the Pursuit of an Ancient Bible

BY

Matti Friedman

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2012

For my parents, Imogene and Raphael Zev, and my wife, Naama

Until then I had thought each book spoke of the things, human or divine, that lie outside books. Now I realized that not infrequently books speak of books: it is as if they spoke among themselves. In the light of this reflection, the library seemed all the more disturbing to me. It was then the place of a long, centuries-old murmuring, an imperceptible dialogue between one parchment and another, a living thing, a receptacle of powers not to be ruled by a human mind, a treasure of secrets emanated by many minds, surviving the death of those who had produced them or had been their conveyors.

UMBERTO ECO, The Name of the Rose

This is a work of nonfiction. Quotations from documents, recorded materials, and my own interviews appear inside quotation marks. In acknowledgment of the inexact nature of memory, quotations recalled by those interviewed do not. Notes on sources appear at the end.

CONTENTS

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

ASHER BAGHDADI: Sexton of the great synagogue of Aleppo.

BAHIYEH BAGHDADI: The sextons daughter.

SHAHOUD BAGHDADI: The sextons son.

DAVID BARTOV: President Ben-Zvis chief of staff.

ITZHAK BEN-ZVI: Israels second president (195263), a scholar, and the founder of the Ben-Zvi Institute.

MEIR BENAYAHU: An aide to Ben-Zvi and the institutes first director.

UMBERTO CASSUTO: A Bible professor sent to Aleppo in 1943 to study the codex.

ITZJAK CHEHEBAR: A prominent rabbi who fled Aleppo in 1952 and went on to lead the exile community in Buenos Aires until his death in 1990.

EDMOND COHEN: An Aleppo accountant responsible for concealing the codex in the 1950s.

IBRAHIM EFFENDI COHEN: An Aleppo textile merchant responsible for concealing the codex. Edmond Cohens uncle.

MOSHE COHEN: Edmond Cohens son. Escaped Syria in 1972.

MURAD FAHAM: The Aleppo cheese merchant who smuggled the codex to Israel.

EZRA KASSIN: A former Israeli military investigator and amateur codex sleuth.

SHLOMO MOUSSAIEFF: A jewelry tycoon and renowned collector of ancient artifacts and manuscripts.

YITZHAK PESSEL: An Israeli agent in Istanbul responsible for the Syria-Turkey-Israel immigration route in the 1950s.

AMNON SHAMOSH: An Israeli novelist, Aleppo born, who wrote the first history of the codex.

ISAAC SHAMOSH: A scholar sent to Aleppo in 1943 to try to bring the codex to Jerusalem. Amnon Shamoshs brother.

ISAAC SILO (pseudonym): A resident of Alexandretta, Turkey, and an Israeli immigration agent from the 1940s until his death in the 1970s.

SHLOMO ZALMAN SHRAGAI: The director of Israels worldwide immigration network in the 1950s.

RAFI SUTTON: A former Mossad agent, born in Aleppo, who carried out his own codex investigation.

MOSHE (MUSSA) TAWIL: The chief rabbi of Aleppo who decided to send the codex to Israel.

SALIM (SHLOMO) ZAAFRANI: An Aleppo rabbi who, along with Tawil, sent the codex to Israel.

INTRODUCTION

IN THE SUMMER of 2008, in a dark underground room at Israels national museum in Jerusalem, I encountered one of the most important books on earth. I had never heard of it. Up a winding flight of stairs from where I stood, in a hushed sanctuary dedicated to the Dead Sea Scrolls, a busload or two of tourists filed reverently past the glass cases containing the parchment celebrities of Qumran, but in the gallery below I was alone.

Off to one side, a bulky volume was open under a dim light. I was struck first by a certain air of dignity about it, a refusal to beg for attention: This book boasted no gold leaf, no elaborate binding, no intricate illuminations in lapis lazuli or scarlet, nothing at all but row after row of meticulous, handwritten Hebrew in dark brown ink on lighter brown parchment, twenty-eight lines to a column, three columns to a page. The margins contained tiny notes added by a different hand. It was open to the book of Isaiah. From the labels I learned that the volume was no less than the most perfect copy of the Hebrew Bible, the singular and authoritative version, for believing Jews, of Gods word as it was sent into the world of men in their language. This lonely treasure and millennium-old traveler was the Aleppo Codex, and it would come to occupy much of my life for the next four years.

I was intrigued by the little I knew of the manuscripts story and by the strange juxtaposition of its significance and its anonymity, and a few months after that first visit, amid my other journalistic tasks as a staff reporter at the Jerusalem bureau of the Associated Pressat the time, these tended to involve maintaining a stream of staccato wire copy from the Middle East describing incessant and fruitless political maneuvering and occasional carnageI found time to make my first attempt to write about it. As I understood it then, the manuscripts story was this: It was hidden for centuries in the great synagogue of Aleppo, Syria, where it became known as the Crown of Aleppo, or simply as the Crown. It was damaged in a fire set by Arab rioters in 1947, concealed, smuggled to the new state of Israel by the Jews of Aleppo as their community disappeared, and entrusted in 1958 to the countrys president, coming, in the words of one of the official versions of the story, full circle. This bound volume of parchment foliosa codexhad been kept intact for many hundreds of years, but a large number of leaves had mysteriously gone missing at the time of the synagogue fire. This hindered a quest by scholars to re-create the perfect text of the Bible, as the Crown had never been photographed and there were no known copies. A few vague theories existed about the fate of those pages, which I duly reported, along with a new attempt to find them by the codexs custodians, scholars of the prestigious Ben-Zvi Institute in Jerusalem. I read some of the available material about the manuscript, interviewed several academics, and filed thirteen hundred words to an AP editor in New York City.

At the time of that articles publication, I did not yet recognize the disappearance of the Crowns pages for what it wasa real-life mystery with clues still hiding in forgotten crates of documents and in aging minds. And I did not see that there was another mystery hidden inside the story, one that turned out to be at least as interesting as the first: how, precisely, had the codex moved from a dark grotto in Aleppo to Jerusalem? I did not imagine, at the time, that there could be much new to say about something so old, and it certainly did not occur to me that the true story of the manuscript had never been told at all.

I would like to say I discerned that something was off about the codexs story and that this is why I found myself thinking even months later about the volume I had seen in the museum. But I discerned nothing, and when eventually I began work on this book, I still imagined an uplifting and uncomplicated account of the rescue of a cultural artifact that was shot like a brightly colored thread through centuries of history, and of its return home. My reporters sense, a certain mental hum alerting me to the presence of a story concealed, began tingling only after I had spent a few bewildering months walking into locked doors.

I met the head of the Ben-Zvi Institute, a government-funded academic body named for the man who was given the manuscript upon its arrival in Israel: Itzhak Ben-Zvi, ethnographer, historian, and Israels president between 1952 and 1963. Though the manuscript is safeguarded at the national museum, the late presidents institute, set among trees in a quiet Jerusalem neighborhood and dedicated to studying the Jewish communities of the East, remains its official keeper. The professor, a polite and careful man, spoke to me at length and then, when I moved beyond generalities and requested access to documents pertaining to the Crown in the institutes archive, stopped returning my e-mails.

Next page