Dedicated to my grand-daughter,

SARAH JANE WALLER

I told Sign-talker the things that are in this book, and have signed the paper with my thumb.

Contents

Listen to the old ones, the wise ones; keep their wisdom within your heart, and understand that wisdom in your mind.

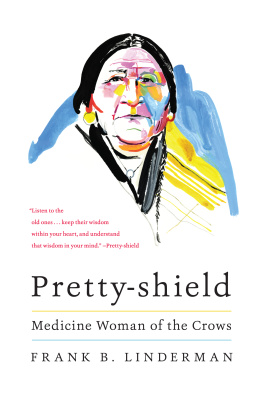

P RETTY S HIELD

IN THE SPRING OF 1931 A CROW GRANDMOTHER SHARED her memories and thoughts, her time, and her home with Frank Bird Linderman, a slender bespectacled writer who had earned a reputation as someone Indian people could trust. The grandmothers name was Pretty Shield. Widowed and seventy-four years of age, Pretty Shield was a vigorous force in both her community and her family. The Crow people recognized her as a healer and woman of power, while her grandchildren knew her as an essential source of strength and wisdom. After the death of their mothers (Pretty Shields two daughters), the grandchildren came to depend on her for sustenance and safety, and she never let them down. From her childhood during the buffalo-hunting days through the pain of reservation years, Pretty Shield lived with spirited independence, honesty, and humorcharacteristics that served her well when she agreed to tell her life to Frank Linderman.

Customary behavior among the Crows, as well as among other Plains peoples, discouraged candid conversations between Indian women and Euro-American men. By 1931 Linderman, who had recently added a biography of the Crow chief Plenty Coups to his publications on Montana Indians and Western lore, doubted that he would ever be able to present the story of a Native womans life. Getting to know them, as he stated in the original foreword to this book, was next to impossible because they were so diffident and self-effacing. But that was an opinion he held before meeting Pretty Shield. Acting with unprecedented autonomy, she dispelled his doubts and changed his perceptions, rapidly and radically.

Pretty Shield viewed herself both as an activist and as a teacher. Recently her granddaughter, Alma Snell, reflected on that vision: After eight decades of life I am still excited to hear about my grandmother.... Even now I feel her steady loving eyes on me, telling me, We cannot determine how long our stay on this earth will be, for it is not for us to say. Do enjoy the many gifts that are ours. Look for them and find them. Get about and move! Nothing is going to come to you, go and find it. Be a good listener, for mentors do not live forever. One day you will move into their place, you will become a mentor like them. Thus the old wise one risked the disapproval of some in the Crow community and worked with Linderman because she wanted to preserve her cultural heritage.

Steeped in Crow oral traditions, Pretty Shield was a masterful storyteller with an extraordinary memory. Her bardner, as she referred to Linderman, was an excellent listener who used written words to make the pages talk. Their collaboration succeeded because they felt comfortable together. Relying on both an interpreter and the use of sign language, the two most frequently spoke in a small abandoned school building. Other conversations took place beneath the trees of a community park, perhaps, according to Alma Snell, so Grandma could enjoy being out in nature. Sometimes Linderman, bearing gifts of tanned animal pelts and silver dollars, visited the one-room home that Pretty Shield shared with her grandchildren. On those occasions, in Almas words, Grandma would brew a big pot of strong coffee, and Linderman would say, This is going to last us a long time. Hed sit and sip and talk to usjust like he was right at home, right at home. Nobody was a stranger to him.

Certainly Montana Indian people were no strangers to Linderman. He had come to the area in 1885 when he was sixteen and Montana was still a territory. Motivated by a fear that the West of my dreams would fade before I could reach it, he pressured his parents for permission to travel to Flathead Lake, a location that, in his words, seemed yet to be farthest removed from contaminating civilization. Two companions made the trip with him, but after a few nights of listening to the wolves that howled dismally around our miserable camp, they abandoned the expedition. Their principal contribution had been to build a small cabin with a highly porous roof. At this cabin Linderman encountered his first Indian... a renowned Flathead warrior who instinctively knew that I was a rank pilgrim. The old warrior and the young adventurer became friends, and as Linderman embarked on his career as a hunter and trapper, he established similarly close connections with other Indians in the Flathead Valley. Much later Linderman, in retrospect, described himself as a friend of the Indian.

He was justified in that description. After exchanging the free life of trapping for marriage he became, at various times, a mining assayer, a newspaper publisher, an insurance agent, a politician, and an author. All the while he maintained and extended friendships in and with various Indian communities. Three tribes honored him with adoption and special names: the Blackfeet called him Iron Tooth; the Crows recognized him as Great Sign Talker; and to the Crees he was The Man Who Looks Through Glasses. Linderman was a particularly significant friend to a group of Crees and Chippewas who, after banding together as landless immigrants from Canada, lived in great poverty. Empathizing with their difficulties, The Man Who Looks Through Glasses personally provided financial assistance, organized efforts for greater economic support, and crusaded successfully to secure a permanent home for themRocky Boys Reservation.

Lindermans experiences convinced him of the need to resurrect and record Indian pasts. The preface to his first published book, Indian Why Stories (1915), begins: The great Northwestthat wonderful frontier that called to itself a worlds hardiest spiritsis rapidly becoming a settled country; and before the light of civilizing influences, the blanket-Indian has trailed the buffalo over the divide that time has set between the pioneer and the crowd. With his passing we have lost much of the aboriginal folk-lore, rich in its fairy-like characters, and its relation to the lives of a most warlike people.

Thus in a strong sense Linderman shared and appreciated Pretty Shields commitment to cultural preservation. That mutual commitment and their compatible personalities made this volume possible. Originally published as Red Mother during the Great Depression year of 1932, it sold rather slowly. Reviewers, however, understood its worth. Ethnographer Robert Lowie, who had spent decades studying Plains Indians, found it more valuable than the autobiography of Plenty Coups. And according to the Christian Science Monitor, Red Mother was needed to complete the picture of the Crows. It should help to dispel the misconception of the Indian woman as a wretched drudge, and it should add to our understanding of the universal kinship of mankind. Indeed it does, on all counts.

The texts and subtexts of Pretty Shields stories illuminate both the process by which she became a Crow woman and the effects of that process throughout her adult life. Through her narrative we meet a girl who loved her family and friends, who absorbed cultural constructions of womanhood (but never became overly serious about them), and who constantly sought excitement, sometimes at great peril. We see Pretty Shield mature to become the wife of a prominent hunter named Goes Ahead, and we grieve with her at the death of a child. We discover that she conversed regularly with animals, accepted the ant people as supernatural helpers, took pride in womens power, and felt honored when allowed to ride her husbands warhorse. But she lamented the fact that Crow men were inordinately fond of war. We learn of the birthing and care of babies, of moving and setting up camp, of the multitude of other skills and tasks required of women, of the close ties they formed as they engaged in their work, and of Goes Aheads role as an army scout at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Then the lessons stop.