The ART of ALLUSION

MATERIAL TEXTS

SERIES EDITORS

Roger Chartier | Leah Price |

Joseph Farrell | Peter Stallybrass |

Anthony Grafton | Michael F. Suarez, S.J. |

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

The ART of ALLUSION

Illuminators and the Making of English Literature, 14031476

Sonja Drimmer

Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Millard Meiss Publication Fund of the College Art Association; the International Center of Medieval Art and the Samuel H. Kress Foundation; and a Publications Grant from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Drimmer, Sonja, author.

Title: The art of allusion : illuminators and the making of English literature, 14031476 / Sonja Drimmer.

Other titles: Material texts.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2018] | Series: Material texts | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018004665 | ISBN 978-0-8122-5049-7 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Illumination of books and manuscripts, MedievalEngland. | Illumination of books and manuscripts, English15th century. | English literatureMiddle English, 11001500History and criticism.

Classification: LCC ND2940 .D74 2018 | DDC 745.6/709420902dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018004665

For my mom and dad

The fifteenth century, it may well be said, was one of the most curious and confused periods in recorded history.... Not the least curious and confusing of its aspects is the story of the book production in that century.

CURT F. BHLER, The Fifteenth-Century Book

CONTENTS

Color plates follow

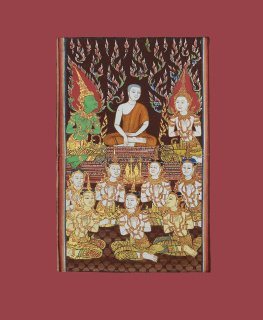

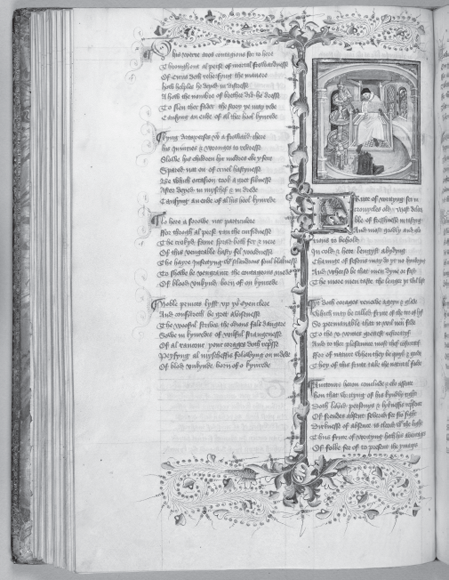

A miniature produced in the middle of the fifteenth century offers an illuminators vision of textual production ( In the center of the composition a man sits in a canopied chair with a slanted tablet resting on its arms. He consults a codex, open on a set of shelves nearby, while seeming to write on the roll that slinks over the edge of his tilted desk. Warmed by the fire at his feet and joined by a watchful cat whose gaze echoes his own, the man enjoys the ease of his cozy environs. The circular walls that embrace him rhyme with the set of round, tiered shelves at his side, a visual simile that compares composition to domestication, a relocation of preexisting texts by writing them anew.

This miniature precedes the following lines from The Fall of Princes, in which the author, John Lydgate (circa 1371circa 1449), pauses to reflect on the value of old texts:

Frute of writyng set in cronycles old,

Most delitable of fresshnesse in tastyng

And most goodly and glorious to behold

In cold & hete lengyst abydyng

Chaunge of sesons may do yt no hyndryng

And wherso be that men dyne or fast,

The more men taste, the lenger yt wil last.

In the image, the illuminator has visualized the harvesting analogies, cued by but not in direct correlation with Lydgates metaphor that compares literature to an everlasting fruit. Just outside the window of the study, a man can be seen sowing in a plowed field. Writing, this visual juxtaposition proclaims, is a creative act of reuse.

Expressing a commonplace, Lydgate praises the backward glance at these old texts as a sustaining activity. Similarly, among the most lapidaryand oft-quotedverses in the oeuvre of Geoffrey Chaucer (d. 1400) is the nearly proverbial

For out of olde feldes, as men seyth,

Cometh al this newe corn fro yer to yere,

And out of olde bokes, in good feyth,

Cometh al this newe science that men lere.

FIGURE 1. Man writing. John Lydgate, Fall of Princes, Bury St. Edmunds (?), c. 1450. San Marino, Huntington Library HM 268, fol. 79v.

Likewise, John Gower (d. 1408) opens his Confessio Amantis declaring,

Of hem that writen ous tofore

The bokes duelle, and we therfore

Ben tawht of that was write tho:

Forthi good is that we also

In oure tyme among ous hiere

Do wryte of newe som matiere,

Essampled of these olde wyse.

These three poets composed some of the first monumental works of Middle English verse that were disseminated in multiple manuscript copies during the fifteenth century. And all three of them imagine the English authors act of composition as a continuative one, an enterprise of renewal rather than pure invention. This poetic imagery has long been recognized as a hallmark of vernacular creativity in late medieval England: influenced by scholastic modes of composition that flourished in universities from the thirteenth century onward and shaped by the growing popularity and demand for translations of Latin and French literature, the first major works of the English literary canon were forged with the tools of intertextuality.

The cornerstone of what came to be Englands canon was laid between the end of the fourteenth and the first half of the fifteenth century, against the background of two defining conflicts with lasting impact: the Hundred Years War (13371453) and the Wars of the Roses (14551485).

This book offers the first study devoted to the emergence of Englands literary canon as a visual and a linguistic event. While the year 1400 is invoked commonly

The newly enlarged scale of vernacular manuscript production generated a problem: namely, a demand for new images. Not only did these images need to accompany narratives that had no tradition of illustration, but they also had to express novel concepts, including ones so foundational as the identity and fitting representation of an English poet. Illuminators had, in Brigitte Buettners useful formulation, to create objects of cognition rather than mere recognition.

A central premise of this book is that the work of illumination both responds and contributes to the entry and circulation of new ideas about English literary authorship, political history, and book production itself in the fifteenth century. My aim is not to devise a theory of literary illustration drawn from English texts; rather, I reverse this operation by examining how images think about English literature. In this introduction I provide a foundation on which to lay claims regarding illuminators generation of these thoughts through allusion, what William Irwin has defined as an indirect reference that calls for associations that go beyond mere What we encounter in the manuscripts of Chaucer, Gower, and Lydgate is a technique for image production that recalls the strategies of literary production that these authors assume. Just as these poets embrace intertextuality as a means of invention, so did illuminators devise new images through referential techniquesassembling, adapting, and combining image types from a range of sources in order to answer the need for a new body of pictorial matter that these poets works demanded. Allusion, in other words, emerges as the dominant mode of pictorial invention in Middle English literary culture.

Next page