Table of Contents

Albion: The Origins of the English Imagination Illustrated London

Biography

Ezra Pound and His World

T. S. Eliot

Dickens

Blake

The Life of Thomas More

Poetry

Ouch!

The Diversions of Purley and Other Poems

Criticism

Notes for a New Culture

The Collection: Journalism, Reviews, Essays,

Short Stories, Lectures edited by Thomas Wright

ILLUSTRATIONS

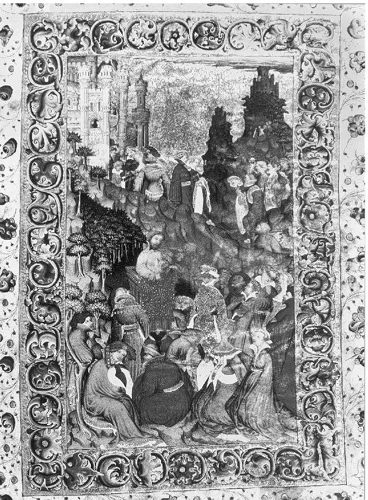

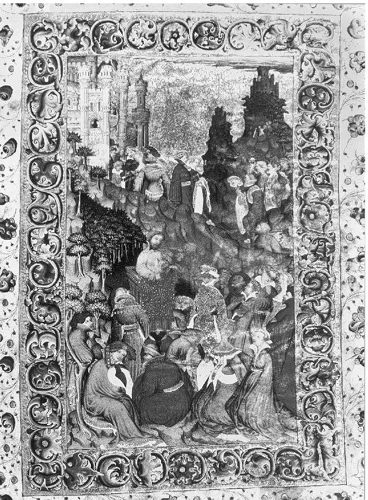

1 Chaucer reading or reciting to the court of King Richard II of England. Painted frontispiece for one of the manuscript copies of Troilus and Criseyde , dating from the fifteenth century. Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, UK/BAL

2 Feeding the chickens. English illuminated manuscript, c.1340. From the Luttrell Psalter. British Library/AKG

3 Butchering and cooking meat, and carrying it to the table. English illuminated manuscript, c.1340. From the Luttrell Psalter. British Library/AKG

4 The Siege of Domme by Sir Robert Knolles (c.13251407) and Sir John Chandos (d.1370). Musee Vonde/BAL

5 Lady dressing her hair with the help of a maid. English illuminated manuscript, c.1340. From the Luttrell Psalter. British Library/AKG

6 Design for Chaucer at the Court of Edward III. Pencil on paper. By Ford Madox Brown (182193). Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery/BAL

7 Philippa of Hainault, French queen of Edward III. Photograph of tomb in Westminster Abbey/BAL

8 Map of Genoa and Florence, from Civitates Orbis Terrarum, coloured engraving, c.1572. The Stapleton Collection/BAL

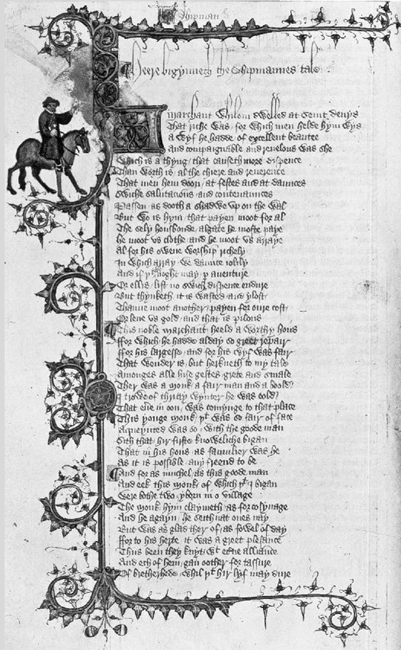

9 The Shipman, detail from The Canterbury Tales. Huntington Library and Art Gallery/BAL

10 The Tower and St. Catherines. Stows Survey of London, 1754. Hand-coloured copper engraving. The Stapleton Collection/BAL

11 John Wycliff

12 The Court of Kings Bench, Westminster Hall. English school, fifteenth century. Inner Temple/BAL

1314 The peasants revolt of 1381. British Library/BAL

15 Richard II presented to the Virgin. By the Master of the Wilton Diptych fl c.139599. National Gallery, London/BAL

16 Tapestry panel of Queen Dido, designed by William Morris (183496) to illustrate Chaucers Legend of Good Women. Part of the designs for Red House, Bexleyheath. Victoria and Albert Museum/BAL

17 Stonemasons, by Bertrand Boysset (13551415). Giraudon/BAL

18 Historiated letter D depicting a philosopher with an astrolabe teaching from The Physics by Aristotle. French school, fourteenth century. Archive Charmet/BAL

19 The Pardoners Tale. Huntington Library and Art Gallery/BAL

20 Here begynneth the knightes tale. Illustration from a book by William Caxton. Woodcut, c.1484. BAL

21 Chaucers tomb in Poets Corner, Westminster Abbey. From a nineteenth-century aquatint. The Stapleton Collection/BAL

The author and the publishers are grateful to the Bridgeman Art Library (BAL) and akg-images (AKG) for assistance with picture research.

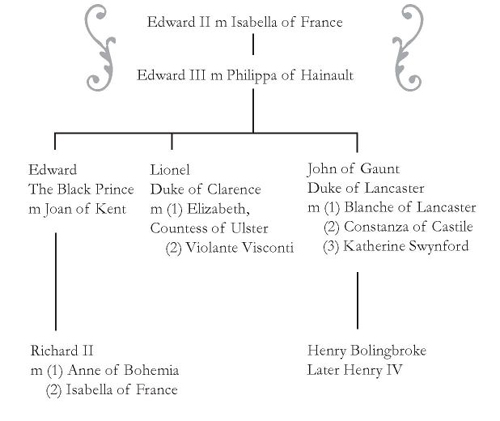

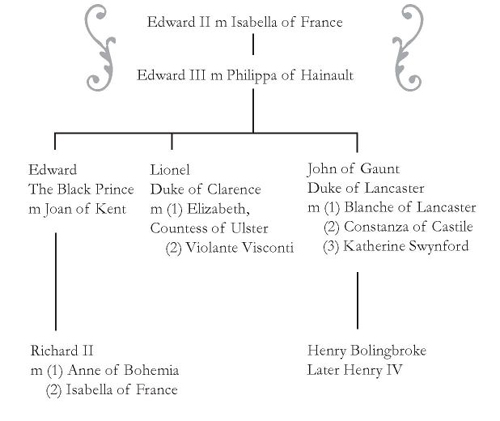

Family Tree Showing the Three English Kings

(Edward III, Richard II, and Henry IV)

and the Two English Princes (Lionel, Duke of Clarence;

and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster)

for Whom Chaucer Worked

Chaucer addressing the court of Richard II

Prologue

There is an image of Geoffrey Chaucer, in early middle age, addressing a small audience of courtiers; he is standing on an enclosed platform (see opposite) with a richly embroidered tapestry draped across its rails. It is not a pulpit but Chaucer has raised his right hand in preacherly attitude; it is commonly assumed that he is reciting from his poetry, but no book is clearly visible. This picture forms the painted frontispiece for one manuscript copy of Troilus and Criseyde; it was executed in the early fifteenth century, but the portrait of Chaucer himself appears to have been copied from earlier originals. He has a forked beard, a moustache, and copious brown hair.

It may also be noticed here that his height is commonly estimated to have been five feet and six inches, average for the period, and that by his own testimony he was portly to the point of being plump. He is not depicted in the clerkly robe of the learned poet but, rather, in the fashionable dress of a courtier. This should be emphasised as one of the most significant aspects of Chaucers art. From the age of fourteen until the very end of his life, he remained in royal service. He was a familiar and indispensable part of the court, and acted as a royal servant for three kings and two princes. That is why the border of this frontispiece is composed of entwined leaves and flowers, in recognition of the playful distinction at the court between the followers of the leaf, the practitioners of chaste fine amour, and the followers of the flower who engage in the worldly pursuit of plaisaunce. Chaucers early verse was part of these love games.

The audience in the picture also repays examination. The figure of Richard II can be clearly seen, in golden robes, and it is significant that Chaucer should be so notably associated with him. Richard, who reigned from 1377 to 1399, was perhaps the most interesting and mysterious of English sovereigns. He was a king devoted to majesty and magnificence, in an age when feudal authority was in retreat. The very circumstances of the portrait, for example, emphasise the theatricality of poetic exposition in a culture possessed by an essentially dramatic vision. The vivid colour of the frontispiece is also an aspect of its drama, since colour was seen in highly allegorical terms: yellow was the colour of jealousy, blue of fidelity, while green was a token of disloyalty. The fourteenth century has been dubbed an age in transition, but all ages are in transition. The difference is that Chaucer came to maturity in a period when the evidence of change was all around him. His own fragmented and discontinuous work, The Canterbury Tales, is itself one indication.

Other figures, within this royal court gathered in a private park, have also been identified with varying degrees of certainty. Richards consort, Queen Anne, has been glimpsed; Chaucers first and most enduring patron, John of Gaunt, has also been seen among the press of courtiers. It has largely gone unremarked, however, that the audience is composed primarily of women. They were seen to be the natural audience for tales and romances of every kind. In succeeding centuries, in fact, the audience for the novel was deemed to be principally female. This may also provide a clue to the tone of Chaucers early and most courtly poetry.

Yet some of the women here do not seem to be listening to Chaucer; the apparently rapt attention of others could also be interpreted as boredom or bewilderment. By indirection this touches upon the nature of artistic invention in the period; it was attentive to the minute and individual details of depicted life. The portrait, like the art of Chaucer himself, is able to provide the illusion of a group in volumetric space together with the delicate rendition of such detail. Yet this passion for realism, if the anachronism may be permitted, is accompanied by the mystery of the overall form. The portrait of Chaucer addressing his audience is surmounted by the image of a procession beside the walls of a medieval castle, yet the meaning of this scene is unclear. Some believe that it illustrates a passage from

Next page