Contents

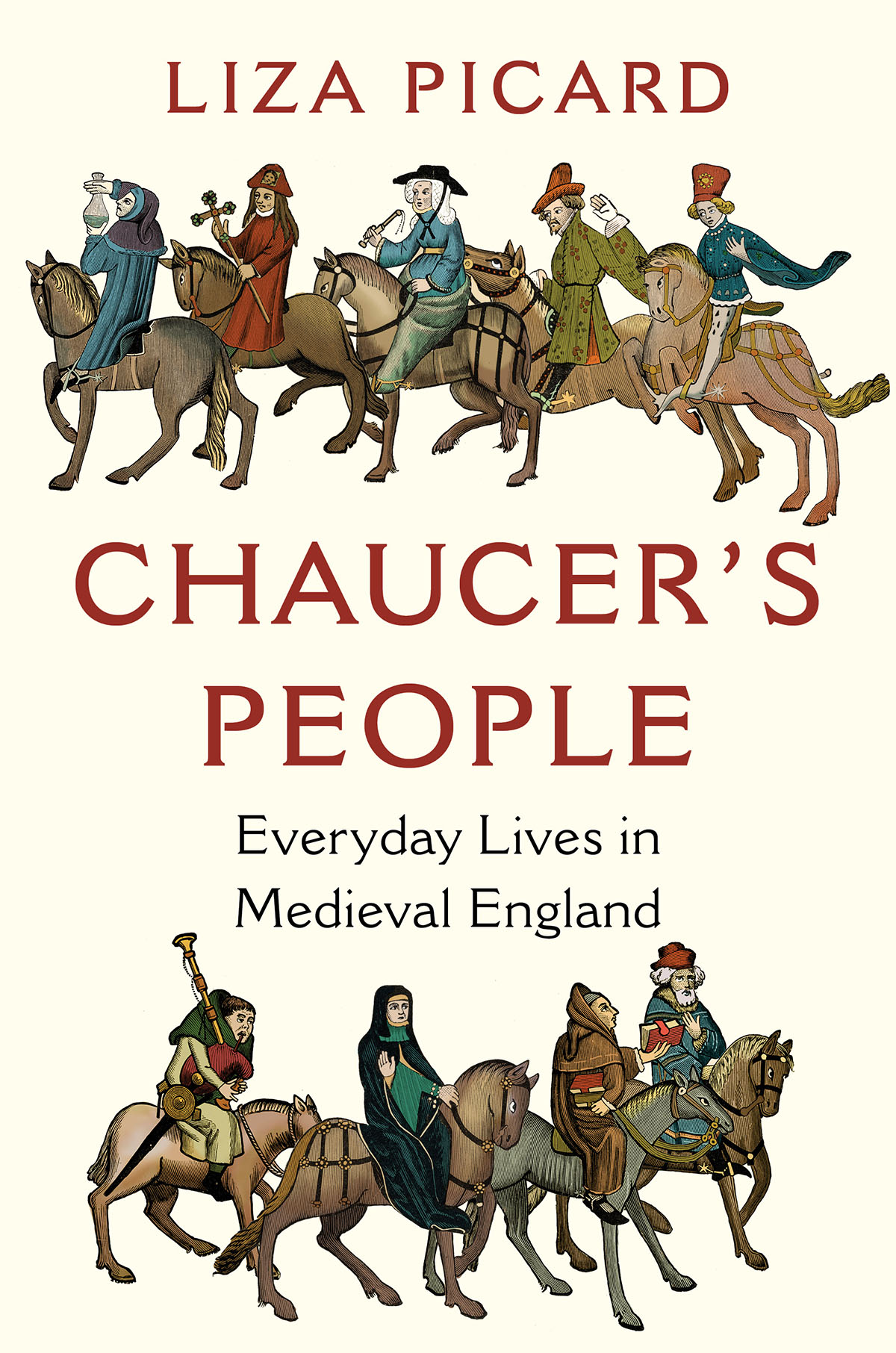

CHAUCERS PEOPLE

Also by Liza Picard

Elizabeths London

Restoration London

Dr Johnsons London

Victorian London

CHAUCERS

PEOPLE

Everyday Lives in Medieval England

LIZA PICARD

W. W. Norton & Company

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York | London

Text copyright 2017 by Liza Picard

Maps copyright 2017 by John Gilkes

First American Edition 2019

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson

an imprint of The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue,

New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Picard, Liza, 1927 author.

Title: Chaucers people : everyday lives in Medieval England / Liza Picard.

Description: First American edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company,

[2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Originally published: Great

Britain : Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018044655 | ISBN 9781324002291 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Great BritainHistoryMedieval period, 10661485. | Chaucer,

Geoffrey, 1400Characters. | Chaucer, Geoffrey, 1400. Canterbury tales. |

EnglandCivilization10661485.

Classification: LCC DA185 .P49 2019 | DDC 942.03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018044655

ISBN 9781324002307 (ebook)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To John, with love

CONTENTS

Geoffrey Chaucer was born, probably, in 1340, and died, definitely, in 1400, by when he had seen a war, a pandemic, a rebellion, and a regime change.

The war was England versus France. It began in 1337 and went on for more than a hundred years, in fits and starts. When it was over, it was called the Hundred Years War. While it was going on, it was called the French War.

The pandemic was a plague known as the Black Death, or the Great Pestilence. In 1348 it killed about half the population of England.

The rebellion of 1381 was the protest by peasants against the burden of taxation. It was not just peasants who rebelled, and they had other grievances besides taxation.

The regime change happened in 1399, when Henry Bolingbroke (see Appendix A) took over the throne from his cousin Richard II (r. 137799), and became King Henry IV (r. 13991413).

People dont change. Their surroundings may change, and their perception of the past and the future, but we share the same impulses and hopes. Chaucer created his pilgrims in the fourteenth century. Here is one view of how they look, six centuries later. All Ive done is to supply some background.

He wrote in Middle English, which has developed into the language we speak. Sometimes hes easily understandable, sometimes Ive modernized him. I hope Ive made the right choices.

I have used the edition of The Canterbury Tales published by Penguin Books in 2005, edited by Jill Mann. I am deeply indebted to her for her permission to do so. Her notes have been invaluable.

I owe huge thanks to Gosia Lawik, of that wonderful institution the London Library. She has patiently and efficiently dealt with my requests for books, and offered suggestions of her own about medieval sources, which have been more than I deserved, and always enlightening. My dear son John has saved me from some medical howlers and encouraged me when I needed encouragement, as well as disentangling the computer tangles in which I excel. My editor Simon Wright has by his gentle, perceptive suggestions kept me from many a blatant error and divagation. I must also say thank you to my friends who have put up with many a chunk of medieval history when they just called by to exchange the time of day.

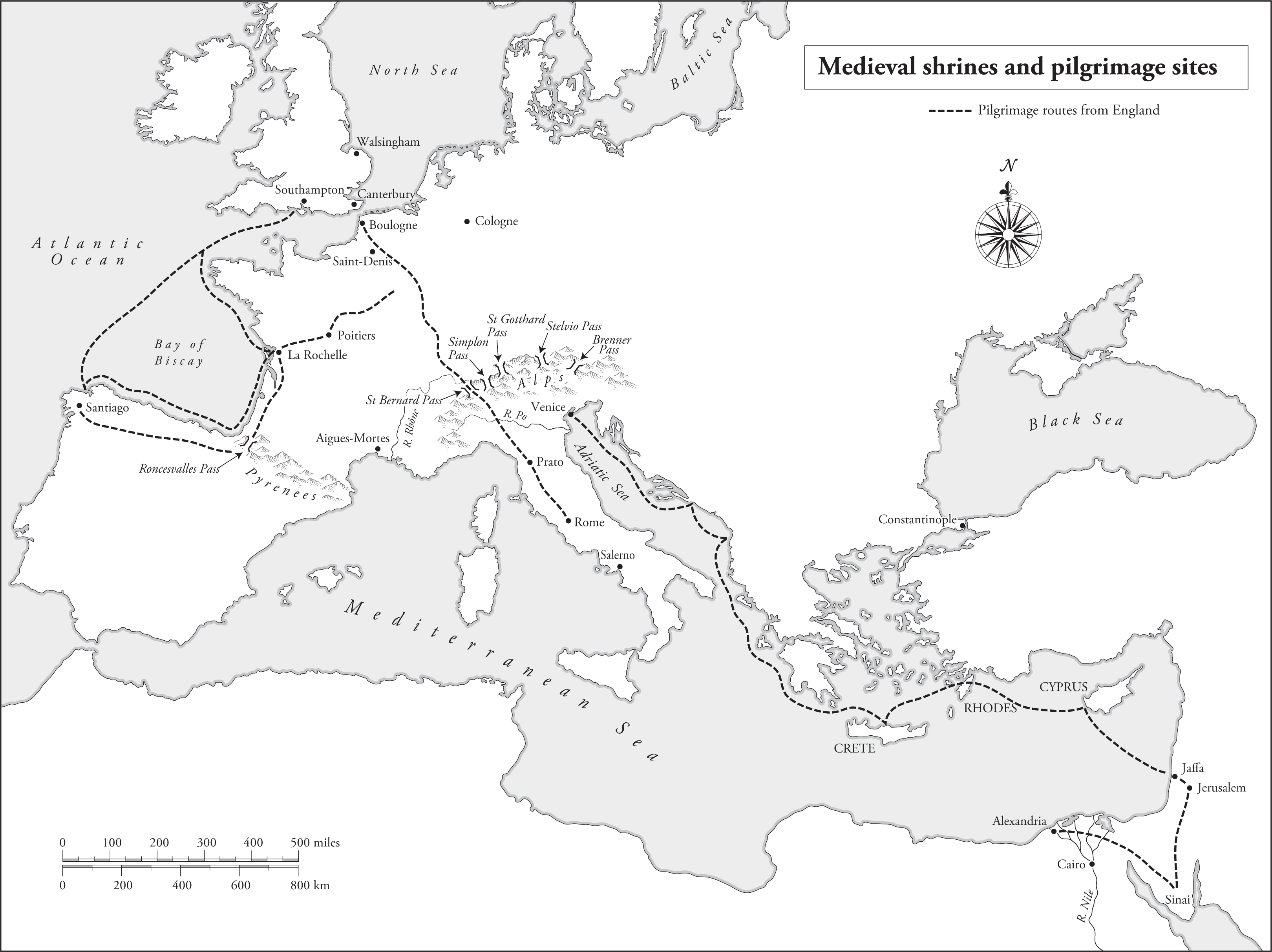

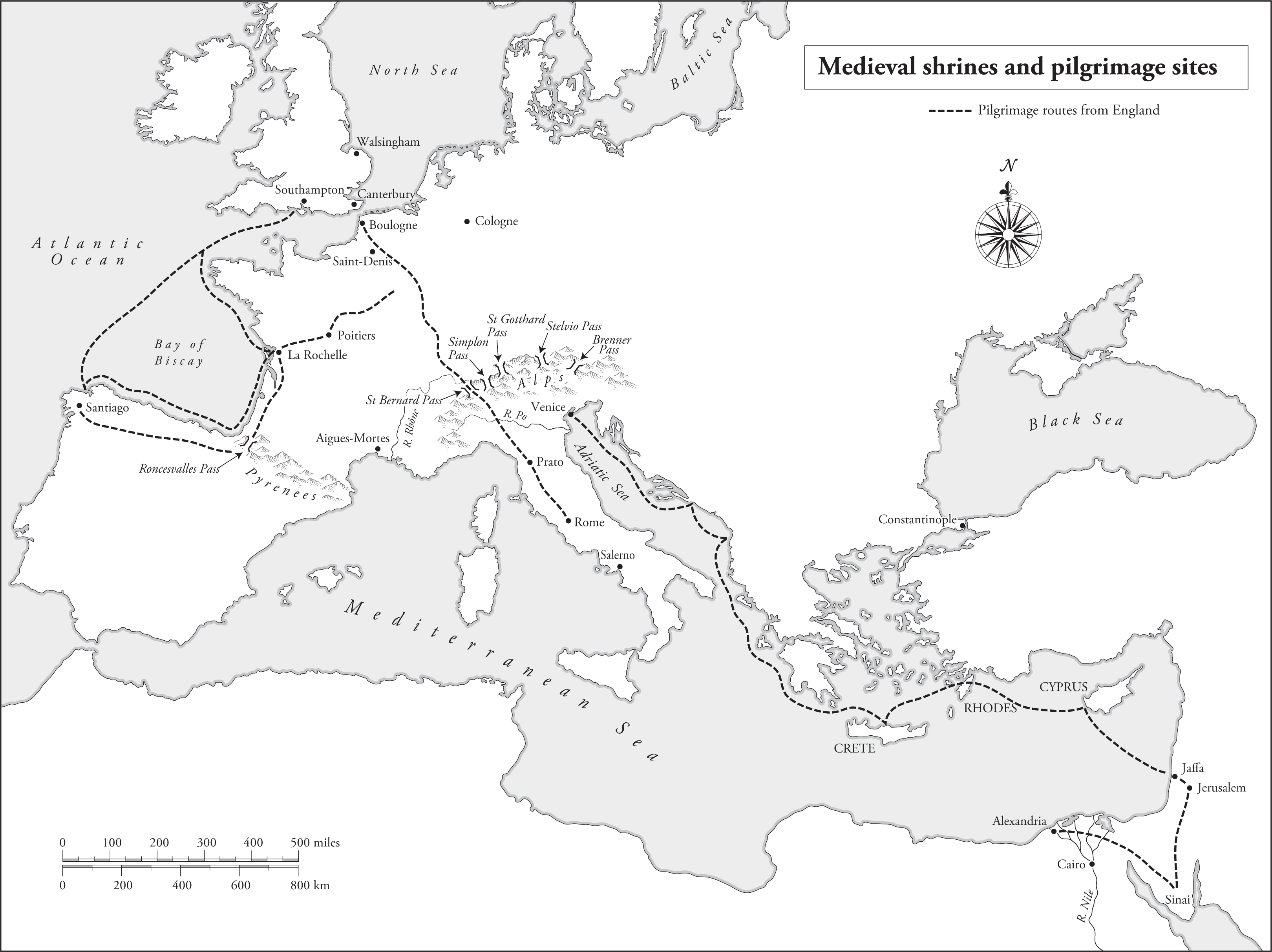

I have been surprised by the wealth of original sources available, in particular the annals of the City of London, and the many chroniclers of their times. Account books for various enterprises have survived, in surprising detail. Perhaps my favourite is the careful record of expenditure incurred by Henry Bolingbroke, just a few years before taking over the throne as Henry IV. He had gone on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, and he had collected some inconvenient mementos on the way, as one does on holiday trips. It cant have been easy, travelling with a leopard and a parrot. The very last entries in his treasurers account of expenditure were a mat for the leopard, and 6 for a cage for the popinjay, plus 1 sh for a cord for hanging it (the cage, not the popinjay).

Ealing

2017

She really came from beside Bath, probably one of the Cotswold villages, not Bath itself, but she has gone down in history as the Wife of Bath, and it seems pointless to correct her address now.

She was certainly eye-catching. Bold was her face, and fair, and red of hue. She had an elaborate wimple round her face and head, and a wide-brimmed hat on the top of it, as big as an archery target.

Her hose were of fine scarlet red. Scarlet was the finest kind of wool cloth you could buy; the word did not at that time mean a colour. But hers were dyed red, another indication of her status since red was an expensive dye. Hose in those days were made of cloth, preferably cut on the cross or bias which would give them a little elasticity, but they had to be full straight [tightly] tyed, by garters below the knee, for women. They were made of one piece from the knee down to the instep, with a seam up the back, and pieces let into the sides of the foot and the sole. It seems obvious to us that knitted hose would have been so much more comfortable, but knitting had not yet taken its place among fashionable garments. Hose are always shown in contemporary pictures as smoothly encasing the leg, which I assumed was an artistic licence until I caught sight of a modern young woman whose jeans were tighter than skin-tight, and certainly encased her legs smoothly, leaving little room for wrinkles.

The Wifes moist new shoes were of soft tanned leather she clearly had no intention of walking anywhere. We are not told The foot mantle was a kind of deep bag usually covering a riders clothes up to knee-level or beyond, to save them from the dust and mud of the journey. But she must have had her feet out of it, to show off her elegant red hose and her new shoes.

English wool, especially from the Cotswolds and Norfolk, had been prized in European trade circles for many years. The Italian textile merchants regularly sent agents over to England to bargain for the best wool. (They sometimes found English place names difficult: for example, Cotswold turned into Chondisgualdo.) The significance of the Wife of Bath lay in the simple fact that she was a weaver and such a skilful weaver that she outdid the weavers in the long-established Continental cloth centres of Ypres and Ghent. Chaucers audience well knew the importance of those cities. Flanders ran a smouldering trade war with English weavers. For many generations Englands prosperity had rested on the export of raw wool hence the Lord Chancellor sat, until recently, on a woolsack, England being still devoted to its history of even half a millennium ago. Suddenly, in historical terms, everything changed. Wool was processed in England and exported to the great fairs in the Low Countries as woven cloth.