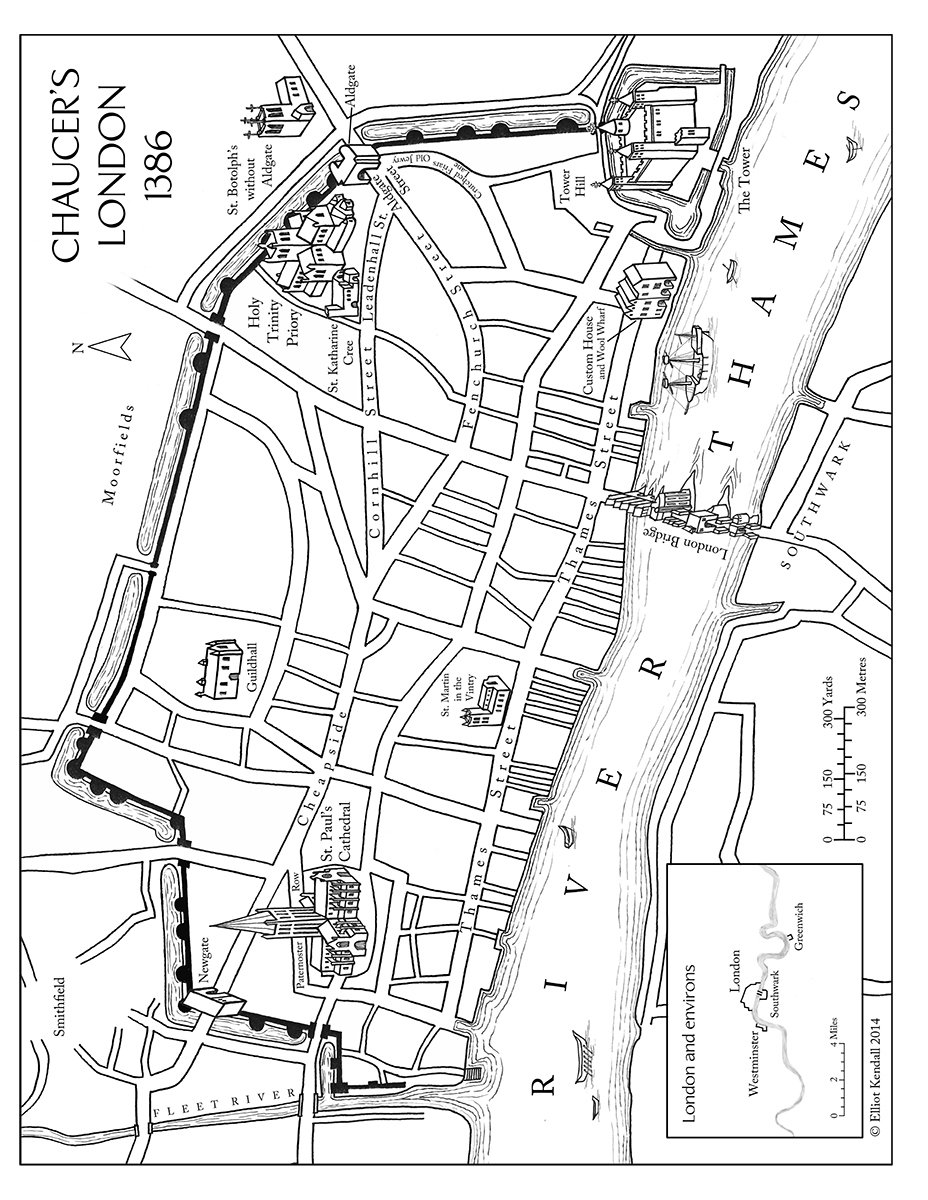

T his book is dedicated to Claire Harman, whose encouragement has sustained me throughout. For advice on London history I owe special thanks to Caroline Barron and Sheila Lindenbaum. Each has significantly influenced my thinking on a number of the matters covered in this book, although neither should be held responsible for any of my particular conclusions. Elliot Kendall designed the London map appearing at the beginning of this volume. In addition to the example of his own work, James Shapiro has offered valuable suggestions on several occasions. I have also received advice from Ardis Butterfield, Susan Crane, Carolyn Dinshaw, and David Wallace. In the longer perspective I have relied upon the cumulative efforts of many scholars who have worked during the past two centuries to identify, edit, and publish Chaucers life-records, including Frederick Furnivall, R. E. G. Kirk, Eleanor Hammond, Edith Rickert, Ruth Bird, Martin M. Crow, and Clair C. Olson.

LIST OF PRINCIPAL FIGURES

Anne of Bohemia. Queen of England, married to Richard II, 138294

Nicholas Brembre. Wool merchant, collector of customs, and four-time mayor of London; ardent supporter of Richard II

Sir Peter Bukton. Knight of the royal household; familiarly addressed by Chaucer in one of his short poems

Geoffrey Chaucer. 1343(?)1400. Courtier, civil servant, and poet

Philippa Chaucer. Lady of Queen Philippas household; wife of Chaucer and sister of Katherine Swynford

Thomas Chaucer. Chaucers son and possible literary executor; prominent supporter of John of Gaunt and the Lancastrian household

John Churchman. London entrepreneur and developer of the 1382 custom house; later creditor of Chaucer

Sir John Clanvowe. Courtier and occasional poet in the manner of Chaucer

Sir Lewis Clifford. Diplomat and advocate of Chaucers poetry

Edward III. King of England, 132777

Nicholas Exton. Fishmonger and mayor of London, 138688; Nicholas Brembres more moderate successor

Jean Froissart. French chronicle writer and poet; well-informed contemporary commentator on the English scene

John of Gaunt. Duke of Lancaster; first marriage to Duchess Blanche, second to Constanza of Castile, third to Katherine Swynford

Thomas, duke of Gloucester. Enemy of Richard II and head of the oppositional aristocratic party, 138589

John Gower. Fellow poet and friendly rival of Chaucer

Henry of Derby. See Henry IV

Henry IV. King of England, 13991414; also known as Henry of Derby, Henry Bolingbroke

Thomas Hoccleve. Clerk; early fifteenth-century poet and devotee of Chaucer

Richard Lyons. Corrupt London financier, slain by irate rebels in 1381

John Lydgate. Monk of Bury St. Edmunds and extremely prolific fifteenth-century poet; respectful imitator and follower of Chaucer

John Northampton. Draper; populist mayor of London, 138183, and adversary of Nicholas Brembre

Philippa of Hainault. Wife of Edward III and Queen of England, 132869

Adam Pinkhurst. London scribe; Chaucers frequent, and probably favorite, copyist

Richard II. King of England, 137799

Paon de Roet. Knight of Edward IIIs household; father of Philippa Chaucer and Katherine Swynford

Sir Arnold Savage. Sheriff of Kent, possible Chaucer host and benefactor

Henry Scogan. Esquire of the kings household, occasional poet, eventual tutor to sons of Henry IV

Ralph Strode. London legalist and bureaucrat with possible previous career as an Oxford philosopher; literary friend of Chaucer

Katherine Swynford. Chaucers sister-in-law; mistress and eventual third wife of John of Gaunt

Thomas Usk. Aspiring writer and ill-fated London factionalist

Thomas Walsingham. Monk of St. Albans and prolific writer of English chronicles

INTRODUCTION

Chaucers Crisis

G eoffrey Chaucer often wrote about reversals of Fortune. One of his most frequent literary themes is the impact of sudden turning points and transformations, blows of fate that alter or upend a situation. Some of his characters withstand such changes, and even find ways to turn them to their own advantage. His Knight, for example, muses upon a young mans cruelly arbitrary death and still counsels his survivors to find ways of seeking joy after woe. The Knights proposed remedy is one that will recur several times in Chaucers poetry: to make virtue of necessity (tomaken vertu of necessitee) by confronting bad circumstances and turning them to advantage if one can.

No wonder Chaucer favored this advice, since his entire career was a series of high-wire balancing acts, improvisations, and awkward adjustments. In his childhood he escaped the disastrous Black Death that ravaged all of Europe. As an adolescent he declined to pursue, or was discouraged from pursuing, his vintner fathers secure career in the London wine trade. He entered the more volatile area of court service instead. Early in that service he was packed off on a military adventure in France, where he was captured and held prisoner until ransomed by the king. He found his way to an advantageous marriage and a reputable position as esquire to the king, but was no sooner accustoming himself to that life than his political allies decided to deploy him elsewhere. They sent him back to London, where he was reimmersed in mercantile culture in the awkwardly conspicuous and ethically precarious post of controller of the wool custom, charged to monitor the activities of some of the richest and best connected and least scrupulous crooks on the face of his planet. He was given occupancy of quarters over a city gatethe very gate through which the rebels would stream (probably under his feet) during the Peasants Revolt. He was intermittently and undoubtedly disruptively tapped for membership in diplomatic delegations, including arduous trips over the Alps to Italy on royal business. Throughout, in court and then in the city, he maintained precarious relations with the most hated man in the realm, the overweening John of Gaunt. He was thrust into awkward and compromising dealings with the most controversial man in London, the unscrupulous wool profiteer Nicholas Brembre. He was in recurrent legal trouble, harassed over unpaid bills, and was the subject of a suit for