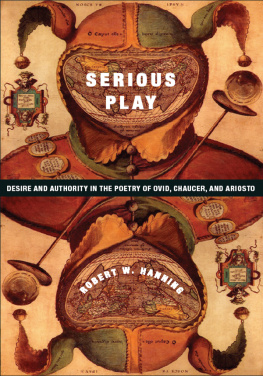

SERIOUS PLAY

UNIVERSITY SEMINARS

LEONARD HASTINGS SCHOFF MEMORIAL LECTURES

The University Seminars at Columbia University sponsor an annual series of lectures, with the support of the Leonard Hastings Schoff and Suzanne Levick Schoff Memorial Fund.

A member of the Columbia faculty is invited to deliver before a general audience three lectures on a topic of his or her choosing. Columbia University Press publishes the lectures.

David Cannadine, The Rise and Fall of Class in Britain 1993

Charles Larmore, The Romantic Legacy 1994

Saskia Sassen, Sovereignty Transformed: States and the New Transnational Actors 1995

Robert Pollack, The Faith of Biology and the Biology of Faith: Order, Meaning, and Free Will in Modern Medical Science 2000

Ira Katznelson, Desolation and Enlightenment: Political Knowledge After the Holocaust, Totalitarianism, and Total War 2003

Lisa Anderson, Pursuing Truth, Exercising Power: Social Science and Public Policy in the Twenty-first Century 2003

Partha Chatterjee, The Politics of the Governed: Reflections on Popular Politics in Most of the World 2004

David Rosand, The Invention of Painting in America 2004

George Rupp, Globalization Challenged: Conviction, Conflict, Community 2007

Lesley A. Sharp, Bodies, Commodities, and Technologies 2007

SERIOUS

PLAY

DESIRE AND AUTHORITY

IN THE POETRY OF

OVID, CHAUCER, AND ARIOSTO

ROBERT W. HANNING

Columbia University Press  New York

New York

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

PUBLISHERS SINCE 1893

NEW YORK CHICHESTER, WEST SUSSEX

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2010 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52639-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hanning, Robert W.

Serious play : desire and authority in the poetry of Ovid, Chaucer, and Ariosto/Robert W. Hanning.

p. cm.(Leonard Hastings Schoff memorial lectures)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-15210-5 (cloth : acid-free paper)ISBN 978-0-231-52639-5 (e-book)

1. Comic, The, in literature. 2. Desire in literature. 3. Authority in literature. 4. Ovid, 43 B.C.17 or 18 A.D.Criticism and interpretation. 5. Chaucer, Geoffrey, d. 1400Criticism and interpretation. 6. Ariosto, Lodovico, 14741533Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Series.

PN56.C66H36 2010

809'.917dc22

2010003740

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

M y mother, may she rest in peace, was guided through her long life by an impressive collection of aphorisms; among her favorites was an open confession is good for the soul. Since I have always tried to be an obedient son, I will begin this volume with a confession, an explanation, and then a few heartfelt statements of gratitude. I confess, then, that I never expected to give the lectures on which these chapters are based at the point in my life, and academic career, when I did. But having been invited to deliver the thirteenth annual Leonard Hastings Schoff Lectures at Columbia University in October 2005, I decided, not without considerable trepidation, to share with an educated general audience my admiration and affection for three European poets whom I have come to know and love through decades of teaching them to undergraduates and graduates, primarily at Columbia University but also en passant at Yale, Princeton, Johns Hopkins, and at the Bread Loaf School of English of Middlebury College and Lincoln College, Oxford. Specifically, I proposed to consider some of the cultural anxieties that underlie, and social or political crises that activate, the comic poetry of Augustan Rome's Publius Ovidius Naso, fourteenth-century London's Geoffrey Chaucer, and early-sixteenth-century Ferrara's Ludovico Ariosto. Ovid's career in Rome coincided with the triumph of centralized imperial power, in the person of Augustus, over the institutions of the Roman republic. Chaucer composed most of his major poetry in the politically fraught and ultimately catastrophic reign of Richard II, deposed in 1399 and subsequently murdered. Ariosto was a courtier and sometime public servant of the Este dynasty, despotic rulers of a small, northern Italian city-state, the independence of which was perpetually threatened by the larger, more powerful political entities that surrounded it. The duchy of Ferrara only survived because the Este sold their services as mercenaries to the highest bidderIn the process entering into cynical and constantly shifting alliances with their grander neighborsduring a period when Italy was under constant occupation by the armies of the several European states fighting for hegemony over all or parts of the Italian peninsula.

As I have taught, so have I learned, and these chapters are dedicated to all the students who have shared my enjoyment and expanded my understanding of Ovid, Chaucer, and Ariosto, but especially to the participants in my graduate seminar on these poetsmy first attempt at treating them all and exclusively in one coursein the fall 2004 semester in Columbia's Department of English and Comparative Literature. Without the insights and enthusiasm of my students, my Schoff Lectures could never have been delivered, which is not to say that they are in any way responsible for errors and infelicities in the revised versions that follow.

The same disclaimer applies to the contribution and support of two dear friends: first, my longtime colleague David Rosand, Meyer Schapiro Professor of Art History at Columbia, with whom I taught many times an undergraduate seminar on myths of love in the art and literature of the Renaissance, in which Ovid and Ariosto are featured players. In the spring of 2005, in chatting with David about this and that, I made the fatal mistake of mentioning that as a result of the wonderful time I had had with the students in that graduate seminar on (with apologies to messrs Pavarotti, Domingo, and Carreras) The Three Poets, I was thinking of attempting, some time in the distant future, a little monograph on them: nothing particularly scholarly, more in the nature of an appreciation (that old-fashioned term!). Scarcely were the words out of my mouth when David was on his way to (or on the phone with) Prof. Robert Belknap, the director of Columbia's University Seminar Program (the immediate sponsor of the Schoff Lectures), nominating me for the next installment in a series to which he (Prof. Rosand) had made such a distinguished contribution a few years earlier. The rest, as they say, is historya history for which I pronounce myself deeply indebted to the University Seminars, to Prof. Belknap, and to his assistant, Ms. Alison Garforthas I suddenly had to face the daunting prospect of actually trying to make sense of these three great comic poets in only a few months, and for what I would have to call their (and my) ideal audience. You must believe, O ideal audience (now metamorphosed into what I hope will be an ideal, or at least tolerant, readership), that I pronounced Prof. Rosand's name in conjunction with short, until recently unprintable locutions more than once during the intervening period of gestation as I struggled to discharge the obligation placed on me by his act of friendship, by my prospective listeners, and above all by those exemplary bards. Now, however, all is writtenand revised for publicationfor better or for worse, so all is forgiven. Seriously, thank you, David, for all you have done for me and been to me over these many years.

Next page

New York

New York