Chaucer Geoffrey - A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde

Here you can read online Chaucer Geoffrey - A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Troy (Extinct city);Turkey;Troy (Extinct city, year: 2014, publisher: Faber & Faber, genre: Humor. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber & Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- City:Troy (Extinct city);Turkey;Troy (Extinct city

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Go, litel bok, go, litel myn tragedye

Go, litel bok, go, litel myn tragedye

V. 1786

The Trojan War was part of the Ancient Greeks ancient history, events said to have taken place a thousand or more years before. Troy did, and didnt, exist. Even the Greeks had trouble finding it. It was part of a series of cities on a hill by the sea in Anatolia. The sea has long since retreated and Anatolia has dissolved into Turkey but the site remains. The seeds of war, like those of tragedy, are usually a series of consequences.

In this case, an impossible judgement and a dangerous promise. Paris, son of the Trojan king Priam, was forced to choose the loveliest among three goddesses. As reward he was offered the most beautiful woman in the world, and set off to claim her. She was Helen, wife of King Menelaus of Sparta. Her abduction (or, as would be asked of Criseyde, did she go willingly?) led Menelaus to rally an army to fetch her back. The Greeks arrived at Troy and surrounded the city.

The story of the siege of Troy is told in Homers Iliad, which also contains the earliest extant mention of Troilus. A prince, and Pariss brother, he turns up before that in various stories in which his role is usually that of extreme youth and early death. Otherwise, he is remarked upon for his valiance. Medieval poets took hold of these old tales and established a practice of free borrowing and blithe reinvention, material now known as the Matter of Troy, an accumulation of versions and variations and component parts. Troilus was given his own story, that of falling in love with a woman called Briseida, by the French poet Benot de Sainte-Maure in his twelfth-century epic, Roman de Troie. This was adapted into a Latin prose version around 1287 by Guido delle Colonne, whose harsh view of Briseida set a lasting tone.

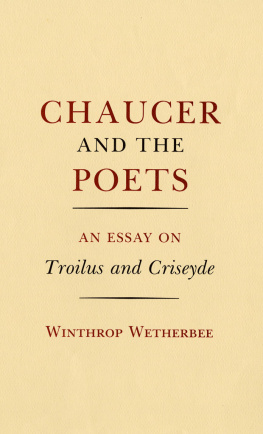

Around 1340, the story was rendered into Italian poetry by Giovanni Boccaccio as Il Filostrato or the one rendered prostrate by love. Boccaccio broke down the romance into steps and strategies like a war or a dance evolved Briseida into Criseida, and introduced Pandarus, the go-between. Chaucer completed his version around 1383, the year he turned forty. He was at the height of his powers. Troilus and Criseyde is generally held to be his greatest work and in terms of English literature as important as Beowulf and Spensers Faerie Queen. It stands alongside another great late-fourteenth-century poem, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.

Although roughly two-thirds of Chaucers text is original, he borrowed hugely from Boccaccio as well as from Guido and de Sainte-Maure, none of whom he acknowledges. Instead he credits a source called Lollius, whom he appears to have invented. Boccaccio, too, is coy about his own starting point. Chaucer takes hold of this story as if he caught it in the air and freely incorporates what it brings to mind of his other reading. He read widely, and across languages, having translated the Romance of the Rose from French, and, from the Latin, Boethiuss Consolation of Philosophy. He darkens Pandarus, casts a searching light on Troilus and listens to Criseyde.

He goes to some lengths to remind us that he is not trying to provide any answers. Neither am I. In activating rather than depicting courtly love, Chaucer unsettles everything, at times to the extent that things just dont add up. You find yourself wondering how Troilus can be hunting in the forest when under siege (Chaucer later mentions, as if in afterthought, that there had been a truce) and the denouement is pinned on the discovery of a brooch that youre not quite sure has been mentioned. They talk like medieval knights when they are ancient warriors, and refer to God but also to gods. Troilus and Criseyde is the greatest account you will ever read of people arguing themselves and each other into and out of love. Troilus and Criseyde is the greatest account you will ever read of people arguing themselves and each other into and out of love.

Like Boccaccio, Chaucer himself intervenes from the start. Whereas Boccaccio was asserting a personal connection, Chaucer is implicating us all: this is the lovers story but it could be yours or mine. As for who does what and why, nothing is simple. Each imperative and response is shown to be made up of densely packed filaments: hope, fear, sympathy, pragmatism, self-protection , ambition, desire, exhaustion I dont imagine that a fourteenth-century author was setting out in a twenty-first-century way to examine the lovers psychology, but that in dramatising their relationship he drew out their inner processes. Chaucer does this most forcefully through his imagery, much of which is borrowed from Boccaccio. What reads like an embroidered emblem in Il Filostrato is here brought to life, unfolding in front of us.

It was the imagery, rather than the story, that made me want to write my own version which is not a version, and certainly not a translation, but an extrapolation. Ive jettisoned characters and scenes, and made some borrowings of my own. Ive taken an image or phrase (which in the Chaucer may be a passing mention or something played out over hundreds of lines) and have used it to formulate each small but irrevocable step in the story. At times these are different aspects of the compacted emotions mentioned above. At others, they are decisions, gestures and (rarely) actions. Ive used a corrupt version of the form Chaucer chose for the poem, a seven-line stanza known as rime royal which has a rhyme pattern of A, B, A, B, B, C, C.

It interests me that he untidied Boccaccios neat eight-line verses (or octaves), and contrived a pattern that suggests circularity as much as development. Seven lines offer a sense of progression without conclusion and that fascinating fifth line doesnt quite fit. Its a spanner in the works; its echoing rhyme, a glance in the rear-view mirror. The thread of the story runs above and below these poems through their titles and occasional subtitles, which Ive placed at the foot of certain pages. These are an active and integral part of a work in which the margins are open and which was conceived overall as a form of detonation. I, too, have caught the story in the air and want to keep it there.

I was also encouraged by the resilience of this story and how over time, and through all its variations, its drama has deepened. The warrior prince, at first no more than a cipher, is filled out as a man trapped by convention in Boccaccios hands and then, in Chaucers, a man trapped in himself. Troilus, Il filostrato, does not fall in love. He falls down, he is felled. The framework of his life gives way, for all its structures, and until Pandarus appears to make things happen, he cannot act. He never quite grasps the idea that love is not a battle campaign, requiring only a strategy, and he never seems to wonder who Criseyde is beyond her beauty and fitness as the subject of a quest.

Who is she, this Briseida/Criseida/Criseyde who has surfaced through these retellings? [A]n hevenyssh perfit creature,/That down were sent in scornynge of nature. Someone too beautiful, unearthly, whose presence makes those around her feel ordinary. But who is she? A widow without children, of some nobility but not equal to royalty, whose father Calchas has betrayed Troy and abandoned her to go over to the enemy. But who is she? A woman of uncertain age, Tendre herted, slydynge of corage, trapped in a besieged city. Her response to Troilus is never less than reasonable and often more realistic than his declarations and dreams. When she is handed over to the Greeks, at her fathers urging, in an exchange of prisoners , he fails to speak up, telling himself he must above all protect her honour.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde»

Look at similar books to A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A double sorrow: Troilus and Criseyde and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.