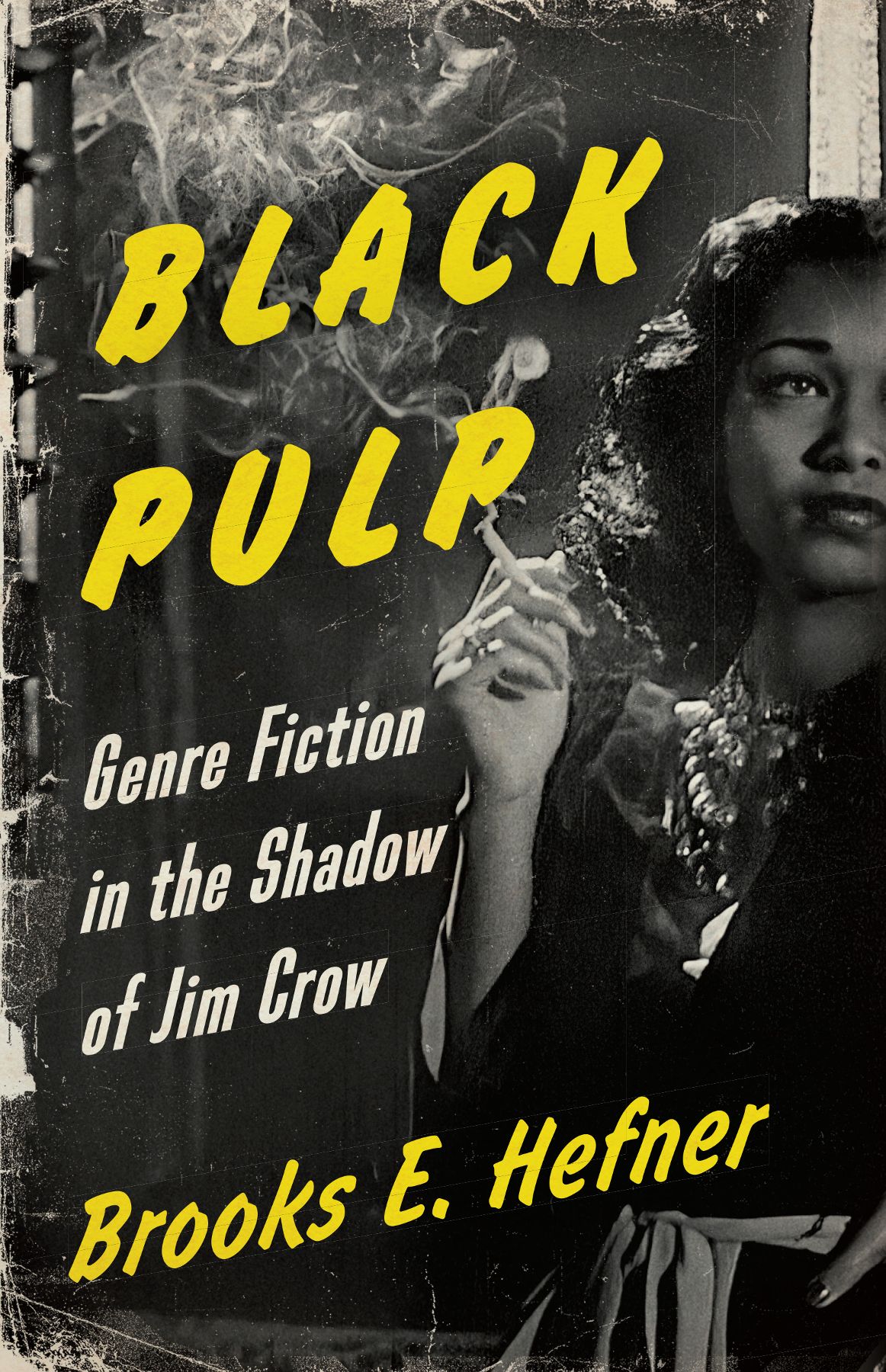

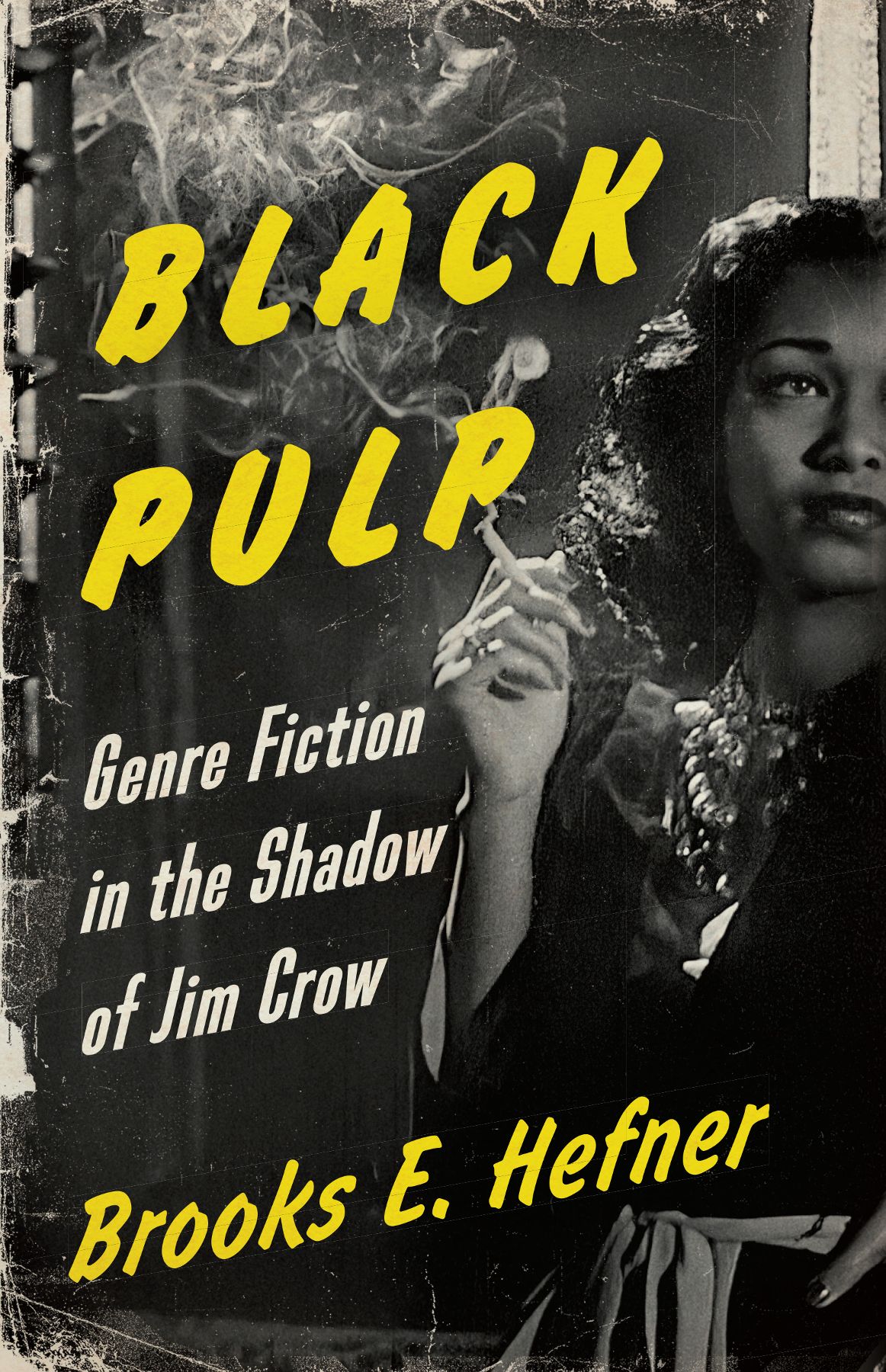

Black Pulp

Black Pulp

Genre Fiction in the Shadow of Jim Crow

Brooks E. Hefner

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

London

Portions of chapters 2, 3, and 4 were published in a different form in Signifying Genre: George S. Schuyler and the Vagaries of Black Pulp, Modernism/Modernity 26, no. 3 (September 2019): 483504; copyright 2019 The Johns Hopkins University Press. A portion of chapter 3 was published in a different form as How It Happens Here: Race and American Anti-Fascist Literature, Los Angeles Review of Books, November 26, 2016.

Quotation from the correspondence of Will Thomas is reprinted by permission of Anne Wilhelen Smith. Quotation from the correspondence of Carl Murphy is reprinted courtesy of the AFRO American Newspapers Archives.

Copyright 2021 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

ISBN 978-1-4529-6678-6 (ebook)

Library of Congress ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021023218

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

Contents

Signifying Genre, Articulating Race

W HEN NEWS BROKE that Jordan Peeles brilliant 2017 horror film Get Out had been nominated for a Golden Globe, fans of Peeles work were no doubt thrilled. Peeles film, one of the most talked-about films of the year, tapped into and transformed long-standing, racist cinematic horror tropes that pitted white minds against Black bodies in a canny updating of body snatching. However, fans were also doubtless perplexed when the films nomination was for Best Motion PictureMusical or Comedy and its lead, Daniel Kaluuya, was nominated for Best Performance by an Actor in a Motion PictureMusical or Comedy. Get Out is definitely not a musical, so what exactly was supposed to be so funny about the story of wealthy whites who, attempting to prolong their own lives, murder young, unsuspecting African Americans and transplant their brains into now-mindless Black bodies? Sure, Peele had made a name for himself as comedian, first in MadTV and later as the co-creator and costar (with Keegan-Michael Key) of the Comedy Central series Key and Peele. But as many commenters noted in praising the film, Get Out was a clear departure from this kind of work, taking scenarios that might have served as a premise for a Key and Peele sketch and transmuting the uncomfortable humor of interracial interactions into a deep sense of horror and dread and a meditation on the value of Black lives. How, then, did a horror film get so terribly misread?

A backlash to this categorization ensued, which prompted Peele to admit that the films own production companies had submitted Get Out under this category, in part because it did not necessarily fit the Golden Globes idea of drama. In the media junket that followed, Peele took the opportunity to meditate onand joke aboutthe intersection of genre and race that occasioned the backlash around Get Outs nomination. In a statement to Deadline, Peele admitted:

When I originally heard the idea of placing it in the comedy category it didnt register to me as an issue. I missed it. Theres no category for social thriller. So what? I moved on. I made this movie for the loyal black horror fans who have been underrepresented for years.... The reason for the visceral response to this movie being called a comedy is that we are still living in a time in which African American cries for justice arent being taken seriously.

Peeles contention that social realities actually condition how genre is understood and perceived is a powerful one; it additionally suggests that direct attention to race and racism within the confines of popular genre might offer new ways of seeing. He also indicates that the response highlights a broader cultural inability to read Black genre for its attention to African American cries for justice. In other words, Black genre and issues of social justice are intertwined in such a way to make them illegible for some audiences. In an interview with Stephen Colbert, Peele riffed on a series of responses to the controversy, joking that he had submitted it as a documentary but also admitting that Get Out sort of subverts the idea of genre.... But it is the kind of movie that black people can laugh at, but white people, not so much. Peeles clever oscillation between generic definitionshorror, comedy, and documentarydemonstrates just how complex genre can be when discussions of race are at its center.

The Whiteness of the Pulps

I began work on Black Pulp not with the puzzling categorization of Get Out in mind but rather with a different but related series of questions. After spending years researching a variety of genres as they were created and developed in the pages of American pulp magazines in the early twentieth century, I found myself asking, where are the Black characters? Where are the Black authors? Where are the Black readers of popular fiction? Pulp magazine horror, like that found in Weird Tales, loved to feature intimidating, brown- and black-skinned figures menacing underdressed white women. Pulp adventure stories frequently sent their Anglo-Saxon protagonists to exotic locales where they could subdue vast, nameless hordes of colonized racial others. But African American protagonists were all but invisible across the entire pulp publishing industry. When characters appeared as more than mere stereotypes, it was rareand usually still unsatisfactory. This was the case when, in 1911, Henry E. Baker and Lloyd Osbourne traded letters in the NAACP organ the Crisis over the representation of the African American character Daggancourt in Osbournes serial The Kingdoms of the World, published in the pulp Munseys Magazine. Baker saw the representation of this better educated colored man as demeaning and humiliating, but Osbourne defended his representation as a kind of incremental progress: Do you realize that the injustice of our (white) people is so colossal that it is already something for a writer to draw a colored man endowed with such elementary good qualities as affection, trustworthiness, honor, industry, self-respect, etc.? Osbournes response here indicates just how far from the norm an African American character with even a modicum of humanity or complexity would fall within the racial politics of the pulp genre system.

Enterprising publishers, engaging what I have elsewhere called genre speculation, could imagine a readership for a magazine like Zeppelin Stories, a subgenre of so-called aviation fiction that exclusively published action stories of lighter than air craft, but the only pulp magazine to engage significantly with African American representation was Harlem Stories, which survived for two issues in 1932 under the small and virtually unknown Jaycline Publishing Corporation.

Regardless, a short-lived and likely poorly distributed magazine from a fly-by-night pulp publisher seemed unlikely to attract a broad African American readership, even with its ability to meet the low bar of making colored folk not monstrosities. It was not the first aborted attempt at a Black pulp. When pulp magazines first started developing genre specializations in the late teens, H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan, well-known editors of

Next page