For Burgy

First published in 2021 by Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright Jonathan Cobb 2021

The right of Jonathan Cobb to be identified as the author of this work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Design and Patent Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic,

photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express

written permission of the publishers.

ISBN: 978 1 78885 473 3

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Papers used by Birlinn are from well-managed forests

and other responsible sources

Typeset by Initial Typesetting Services, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A.

Introduction

It is certain that not a drop of rain falls without the express command of God.

John Calvin, Institutes

As a young pupil, it would have been interesting to learn why the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland had a Royal Navy and a Royal Air Force, but an apparently non-royal army. It was just the Army. Did this reflect some subtle class distinction given military meaning or was it perhaps a temporary designation while it waited for the return of royal patronage? Yet the years went by and nothing in the armys title changed. It was only later that the penny dropped with the knowledge that this title, rather than the result of oversight, was in fact the consequence of a part of history in which a professional body of military men became intimately involved in a type of British state that was experienced neither before nor since.

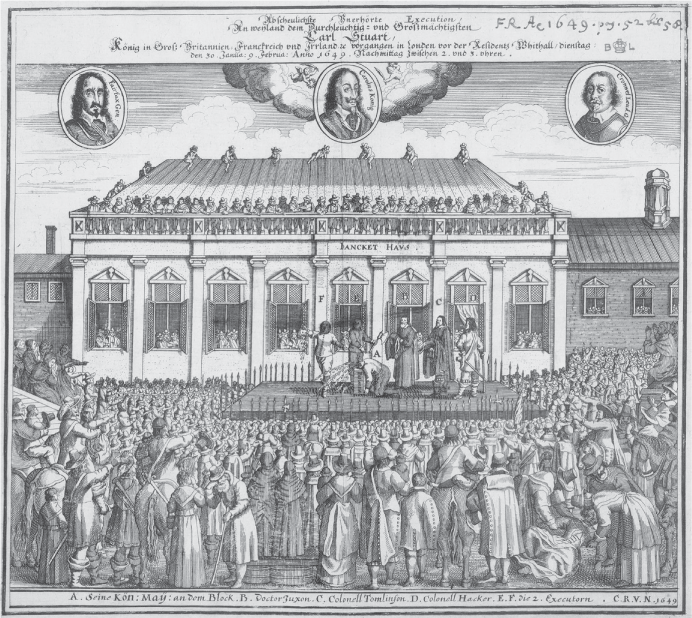

The period between the defeat of the royalist army at Naseby and the Restoration of the monarchy with Charles II encompassed a series of experiments in the governance of the British Isles and Ireland as the victors of the civil wars groped for a settlement that would ensure peace in the former realm. This quest was both religious and political in character, for the wars had been as much about rival interpretations of Protestantism as a challenge to monarchical authority in the early modern state. An interval which witnessed the emergence of the army as the primary arbiter of government coincided with an extraordinary catharsis of religious belief and the consummation of the passions ignited by the Reformation. It was also a time in which the quasi-military political culture to which the civil wars gave rise brought a new and harsher edge to acts of British colonisation that some argue marked the true beginnings of the British Empire. Indeed, that span of a mere fifteen years is arguably one of the most dynamic periods of modern British history. The discredit to which Charles I had brought the institution of monarchy, and the fierce intensity that characterised the later stages of the civil wars pointed to a fundamental change in the future governance of the British Isles and Ireland. The time had seemed ripe for a new order resting on a bedrock of the godly and sanctioned by an Almighty who had already delivered providential military victories for the future makers of the Republic.

The dynamic of the republican era can seem chaotic. In an effort to marshal some sense of order from the frequently shifting kaleidoscope, a number of accounts are coloured by attempts to precisely define the revolutionary demographic that populated this extraordinary epoch. This is particularly true of narratives that err towards a determinist view of history, often based on the perceived clash of class and economic interests. Yet classifications such as the natural classes of government and the emerging middle class are rarely if ever found in sources of the period. Contemporary chroniclers, like the royalist Edward Hyde, refer more enigmatically to persons of quality and degree. Further subdivisions into Presbyterians, Independents and Commonwealthsmen are more helpful in understanding the motivations of the protagonists of the period, and were terms used by contemporaries. But the strands of religious and political thought that they are assumed to define distinctly often blurred and frequently merged. Across them all fell the shadow of the sword.

The stage-set of the period was populated by a cast of colourful characters who frequently belie the drab hues in which it was subsequently painted by some historians. There were poets and social reformers as well as princes, soldiers and religious fanatics. These individuals, often with a great deal of moral and physical courage, redefined what it meant to be devout, made proposals for the further evolution of the state and articulated a philosophy of the community of citizens that is of continued relevance to modern institutions. But in their common attachment to the idea of a citizenry under God, they were far less revolutionary than radical. Political debate was most frequently articulated and settled by reference to Scripture. It was also an era in which the spread of literacy saw the emergence of a distinctive female voice in a society where the primacy of men over women was held to be axiomatic. The contemporary diaries, letters and poems of the likes of the Puritan Lucy Hutchinson, the royalist Ann, Lady Fanshawe, the matchless Orinda and the uncrowned Queen Henrietta Maria reveal an acute sensibility about the tenor of the times and the motivations of the protagonists. Unlike the memoirs of some of the male participants that were written up long after the events they described, a number of the women capture the vigour and immediacy of the events as they were unfolding.

Central to an understanding of this dynamic period is the professional fighting force brought into being as the New Model Army in 1645. It was fundamental to the success of the parliamentary cause in the civil wars and provided a bulwark and arsenal to the new regime. But the ethos and needs of the soldiers (particularly as regards to arrears of pay and indemnification for their acts of rebellion) increasingly came into conflict with those of the civil state. The spiritual orientation of troops, which was so important to both their morale and sense of identity, contributed to the friction in the nations religious arrangements as the civil authorities tried to square the circle between public conformity, and personal belief and conscience. Although the direct intervention of the army in politics in 1647 and again in late 1648 led ineluctably to the execution of the king, the temperament and conservatism of its commander, Sir Thomas Fairfax, ensured that the architecture of the new state was largely left in the hands of the civilians. The further deployment of the army after the defeat of the royalists in the second civil war was as much driven by the civil establishments desire to keep it at arms length as to any incipient imperial design. Yet despite the decisive military victories that ushered the Republic into being, the subsequent interventions of the army in politics, and the rule of the major-generals, merely confirmed the unsuitability of soldiers to be the principal source of governance in an overwhelmingly civil state.