The Publisher would like to thank Roy Freeman for the use of the illustrations in the Foreword.

Copyright

Foreword to the Dover Edition Copyright 2014

by Todd DePastino

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

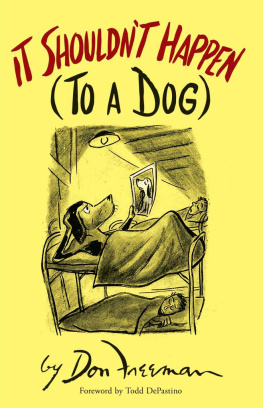

It Shouldnt Happen (to a Dog) is an unabridged republication of It Shouldnt Happen, originally published in 1945 by Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York. Todd DePastino has supplied a new Foreword to this edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Freeman, Don, 1908-1978.

[It shouldnt happen]

It shouldnt happen (to a dog) / Don Freeman ; foreword by Todd DePastino.

pages cm

Summary: Recounted chiefly in winsome illustrations, this fantasy of a GI whos transformed into a dog offers a witty take on WWII-era life among soldiers and on the home front. Wonderful fun. Chicago Tribune Provided by publisher.

eISBN-13: 978-0-486-78210-2

1. American wit and humor, Pictorial. 2. United States. ArmyMilitary lifeHistory20th centuryPictorial works. I. DePastino, Todd, writer of supplementary textual content. II. Title.

NC1429.F6677A4 2014

741.56973dc23

2014018925

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

78210701 2014

www.doverpublications.com

Foreword to the Dover Edition

At a glance, this first publication since 1945 of Don Freemans It Shouldnt Happena book the cartoonist Seth has called an important signpost on the way to the graphic novelmight seem of interest only to antiquarians or aficionados of comics history. But this book about the adventures of a young man drafted into the army and turned into a dog is, in fact, a masterwork of satiric allegory that championed the cause of racial equality, sparked controversy when first published, and still resonates today.

Its a tribute indeed to the democratic principles with which the United States fought World War II that they were liberal enough to permit Don Freeman, himself a soldier, to publish this book during wartime. Americas enemies didnt allow such sharp social critiques, no matter how tempered, as this book is, by tenderness, humor, and a good-natured faith in ordinary citizens. Of course, if all readers were like the reviewer who declared there is nothing serious about It Shouldnt Happen [it] is pure fantasy, then Don Freeman wouldnt have had to fret about stirring trouble. More worrisome was the hysterical New York Times review of August 26, 1945, which contended that It Shouldnt Happen was race propaganda calculated to encourage bitterness and hatred [and] to suggest that justice is best achieved by violence. This reviewer, at least, got the point of the book, even if he grossly distorted it for a reactionary purpose.

This harsh reception of It Shouldnt Happencoming within days of Japans surrendermarked the reigniting of a culture war first kindled in the Great Depression and dampened by Pearl Harbor. The war years were a time out of time for America, when life plans and culture warswere put on hold. Finishing school, advancing a career, even buying a new car or stove all had to wait, and that included the aspirations of workers, ethnics, and African Americans. These groups had struggled during the 1930s for union recognition, Civil Rights, and New Deal social protections. Bolstering this movement was a broad upsurge in the popular arts that scholar Michael Denning has called the cultural front, a second American Renaissance involving artists, musicians, and writers ranging from Woody Guthrie and Duke Ellington to Orson Welles and cartoonists laboring in Disneys studios. The war effort muted the insurgency, as everyone fell in line to support the Arsenal of Democracy in its global war against fascism. When that war ended in the summer of 1945the time Don Freemans cartoon satire was releasedthe cultural front was poised for a breakthrough. Victory in Europe and the Pacific had rid the world of Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo. Now was the time, many liberals and leftists believed, for Jim Crow to join them in the dustbin of history.

Don Freeman had been a part of the cultural front from the very beginning, when at the age of twenty-one he hitchhiked cross country to New York City, arriving days before the stock market crash of 1929. He came to New York as a dance band musician, playing trumpet in nightclubs and at wedding receptions, while taking classes at the famous Art Students League with Ash Can School founder John Sloan. Sloan was one of the first modern realist painters to use his brush to further the causes of Socialism and social justice. Sloan encouraged Don to do what he loved: wander the bustling streets and sketch them in all their bewildering diversity. He went everywhere and sketched everyone, especially the marginal and down-and-out, whom he captured often with humor and always compassion. Dons boyhood fondness for the theater blossomed in New York, where he attended plays as often as he could, sketchbook in hand. Dons New York sketches quickly numbered into the thousands. His only worry, he said later, was that the store would run out of drawing paper.

A turn in career happened late one night as he was returning from an Italian wedding reception. Busily sketching the subway scene, he stepped off the train at Sheridan Square before realizing hed left his trumpet behind. He swung round as the doors closed and watched his horn, still on his seat, disappear into the darkness. His response to the lost moneymaker was characteristic of the resilient and entrepreneurial Don. He took a bundle of his Broadway sketches to the offices of the New York Herald-Tribunes drama department. They began publishing his work, and Don became a professional artist.

Graphic artists and painters then and now must master many skills to survive, and, in addition to selling his theater drawings to magazines and newspapers, Don turned to printmaking and lithography. For a while, he made posters for the New Deal WPAs Federal Arts Project. Then, he turned to book illustrations, providing, for example, the pictures to William Saroyans words in The Human Comedy. He even self-published his own his subscription magazine, Don Freemans Newsstand, One Mans V iew of Manhattan, or, All the News that Fits to Prints. Selling initially at fifty cents a copy, the Newsstand bristled with color and energy, chronicling through drawings and Dons commentary the life of the city. As art historian Michelle Gabriel put it, No other artist has been credited with recording so faithfully and with such sensitivity the drama of New York City as Don Freeman. Other artists called him the Daumier of New York, in reference to the legendary French caricaturist, whose drawings captured and satirized nineteenth-century Parisian society, eventually landing him in jail.

Don Freeman almost suffered a similar fate, but not because of his drawings. In the summer of 1943, Don received his draft notice. Any observer could have predicted that a thirty-five-year-old left-wing artist would not likely find the army a comfortable fit. Its safe to say that most of the other 10 million American men drafted into service werent happy either. Ordinary Americans walking around free one day suddenly found themselves regimented by military autocrats and subordinated at the bottom of a very tall hierarchy. Famed combat cartoonist and infantry sergeant Bill Mauldin called the army a caste system where officers were nobility and enlisted men peasants. The caste system makes it a degrading and humiliating thing to be an enlisted man, and it shouldnt be, he said. New inductees faced a training regimen designed, it seemed, to debase the soldiers humanity to something lesser, such as a dog or a tool.