Preface

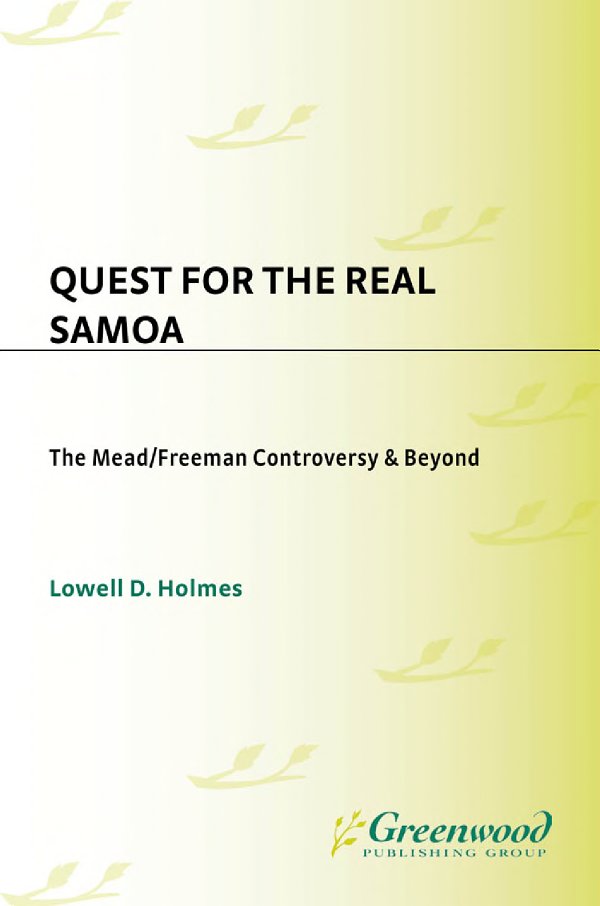

Why have I written this book? Is it because I so greatly revered Margaret Mead that I do not wish to have her memory tarnished? Is it because I am an American and therefore feel committed to support the theoretical framework of Franz Boas, the "Father of American Anthropology?" Or is it because my career as a cultural anthropologist has been so productive and so distinguished that I now want to share my special knowledge with the scientific world?

To begin with I owe nothing special to Margaret Mead.

I left Northwestern University in 1954 to begin fieldwork in Pago Pago. Although I wrote to Margaret Mead as soon as I arrived in Pago Pago, my response from her could hardly be described as friendly. Apparently, Mead thought that her former classmate at Columbia, Melville Herskovits, had put me up to some mischief. She maintained that I should have come to New York and spent time with her and her field notes, and this would have been an indication of my sincerity and good faith. After her initial letter I did not hear from her again until I wrote requesting some special information.

One day while reading Coming of Age in Samoa I turned to the appendix and studied the case histories of the teenage girls Mead had worked with in Ta'u village. Some of the girls appeared to be deviants while others were quite conventional in their behavior. It occurred to me that it might be interesting to follow up on these people and see how the life histories of the deviants might have differed from those of the conventionals over 28 years. I wrote Mead about my ideas and asked for the real names of the girls, since those in Coming of Age in Samoa were obviously fictitious. She wrote back to say that she had to protect the identity of the girls for ethical reasons but that if I would reconstruct the composition of all the households in Ta'u village for the period of 1925 that she would reveal the households in which the girls lived. This was never done because, after taking a census of the village and comparing it with one taken by the government four years earlier, I found that discrepancies were numerous and in some households as much as 50 percent of its composition was different. The task of reconstruction would have been almost, if not completely, impossible and would have taken much more time than the findings would have been worth.

During my time in the field Mead was helpful, however, and she often sent me photocopies of unpublished documents, such as William Churchill's Fa'alupega i Manu'a, which was important in understanding village political structure. I never thought at the time that my restudy of Margaret Mead's work would in 1983 become vitally important in sorting out the facts in anthropology's greatest controversy in 100 years, the debate brought on by the publication of Derek Freeman's Margaret Mead and Samoa: the Making and UnMaking of an Anthropological Myth.

Upon my return from Samoa in 1954 my relationship with Mead was one of storm and stress at best. My first book, Ta'u: Stability and Change in A Samoan Village (1958), was given a terrible review by her in the American Anthropologist. Some years later Margaret mellowed a bit toward me, and I frequently had the opportunity to sit down and carry on a friendly discussion about what we shared in commona knowledge of Samoa and Samoans. We occasionally appeared on panels together discussing Polynesian issues, but I was hardly a protege of this eminent anthropologist, although she often sent me copies of letters she had written to people about Samoan matters. On one occasion she recommended me to someone as a consultant on Samoa, and she even directed one scholar to me with the recommendation that I was more informed about the recent cultural developments in Samoa than she.

While I was educated in the Boasian tradition by a student of Boas, Melville Herskovits, it was a theoretical tradition which I saw as embracing both cultural and biological aspects of the nature of the human animal and one which rejected all forms of deterministic thinking. I could not have accepted anything less.

The importance of culture in the lives of human beings is for me an important given, not just a loose variable in an otherwise stolid theory. The influence of culture as a vital force in human behavior has been a major ingredient in the scientific thought of most recognized anthropologists, from Edward Tylor to Franz Boas to Alfred Kroeber to Leslie White to Gregory Bateson. Even the British who tend to talk about "society," "structure," and "function" but rarely "culture," see human behavior as a product of both traditional mores and biological needs.

My career in anthropology has hardly been so extraordinary that I feel compelled to pass on a series of "truths" about the nature of mankind, although my experience in Samoa and other cultures has provided me with some insights into human behavior that armchair anthropologists never learn. I believe I have learned a few things about how to study a society that is not my own and I am aware of the major pitfalls in field research. I must admit that I owe a great deal to Derek Freeman, as do most Samoan specialists these days, for rescuing all of our careers from obscurity. With all the mayhem going on in the world today people tend to forget about a peaceful little spot like Samoa.

Much of what I have included in this book has appeared in other articles and books that I have written during my thirty-year career as an anthropologist. The volume is therefore somewhat of a compilation; some sections have undergone major rewriting and other parts have been used with only minor revision. Therefore I would like to note the particular materials I have drawn upon and thank the original publishers for the reuse of the data. I would like to thank the Polynesian Society who originally published my book Ta'u: Stability and Change in a Samoan Village, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston for use of sections from Samoan Village, and I would like to acknowledge the fact that I have drawn upon data from my doctoral dissertation at Northwestern University (1957) and from the following periodicals: Journal of American Folklore, Current Anthropology, American Anthropologist, The Sciences, Quarterly Review of Biology, Canberra Anthropology, Journal of Psychological Anthropology, Anthropologica, Journal of Missiology and An thropological Quarterly. I have also drawn upon material previously published by me in the Oxford University Press volume Land Tenure in the Pacific and the Wiley and Sons book Anthropology, An Introduction. To my wife, Ellen, for her services as a dedicated editor and proof reader and to my secretary, Georgia Ellis, who spent long hours at the word processor, I offer my sincere thanks.