Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For the men in my life Dale, Tommy, Andre, and Theron

This last night of waiting for mail is dreadful. I cant read, I cant write coherently. I cant sit still. This sad passivity of the last three weeks is doomed to burst tomorrowand into what new encompassing gloom I wonder.

M ARGARET M EAD

The importance of lettersfor Margaret Mead and her intimatescannot be overstated.

For individuals who were venturing off to faraway and untraveled lands, alone and without a roadmap, letters were a lifeline home. At a time when the telephone was a relatively new invention and long-distance calling did not exist, they had no other way to emotionally connect themselves except through the written word. Letters were the way they recounted their experiences, explored their innermost thoughts, exorcized their demons, and made love.

During the 1920s, the time it took a letter to find its way by rail to a remote outpost could be three weeks, by ocean liner six. For the individuals who populate these pagesLuther Cressman, Ruth Benedict, Edward Sapir, and Margaret Meadthe arrival of the mail was often cited as the most anticipated moment of the day. Margaret Mead made a habit out of saving every letter she receivedsave for the bundle she ceremoniously set fire to on a beach in Samoa in January of 1926.

Now, nearly one hundred years later, I, too, have gained my own appreciation for these letters. Through them I have been able to enter the world of the young Margaret Mead, to get to know her as she was coming of age, in the years before she became famous.

Meads correspondence, missives that number in the thousandsboth written by her and written to heris housed in the U.S. Library of Congress. Most are handwritten, some scrawled in haste, in misery, or erotic passion. As a collection they reveal a side of Mead that she successfully hid from the world during her lifetime and for many years after her death. Thanks to the advent of digital photography, I have been able to store them in my own computer, decipher them, and study them.

What follows is a story told by Mead and her closest confidants. Anything between quotation marks is based on the written record. Scenes and dialogue have been reconstructed out of the actual words and memories of the participants.

Sometimes sleep will not descend upon the village until long past midnight; then at last there is only the mellow thunder of the reef and the whisper of lovers, as the village rests until dawn.

M ARGARET M EAD, C OMING OF A GE IN S AMOA

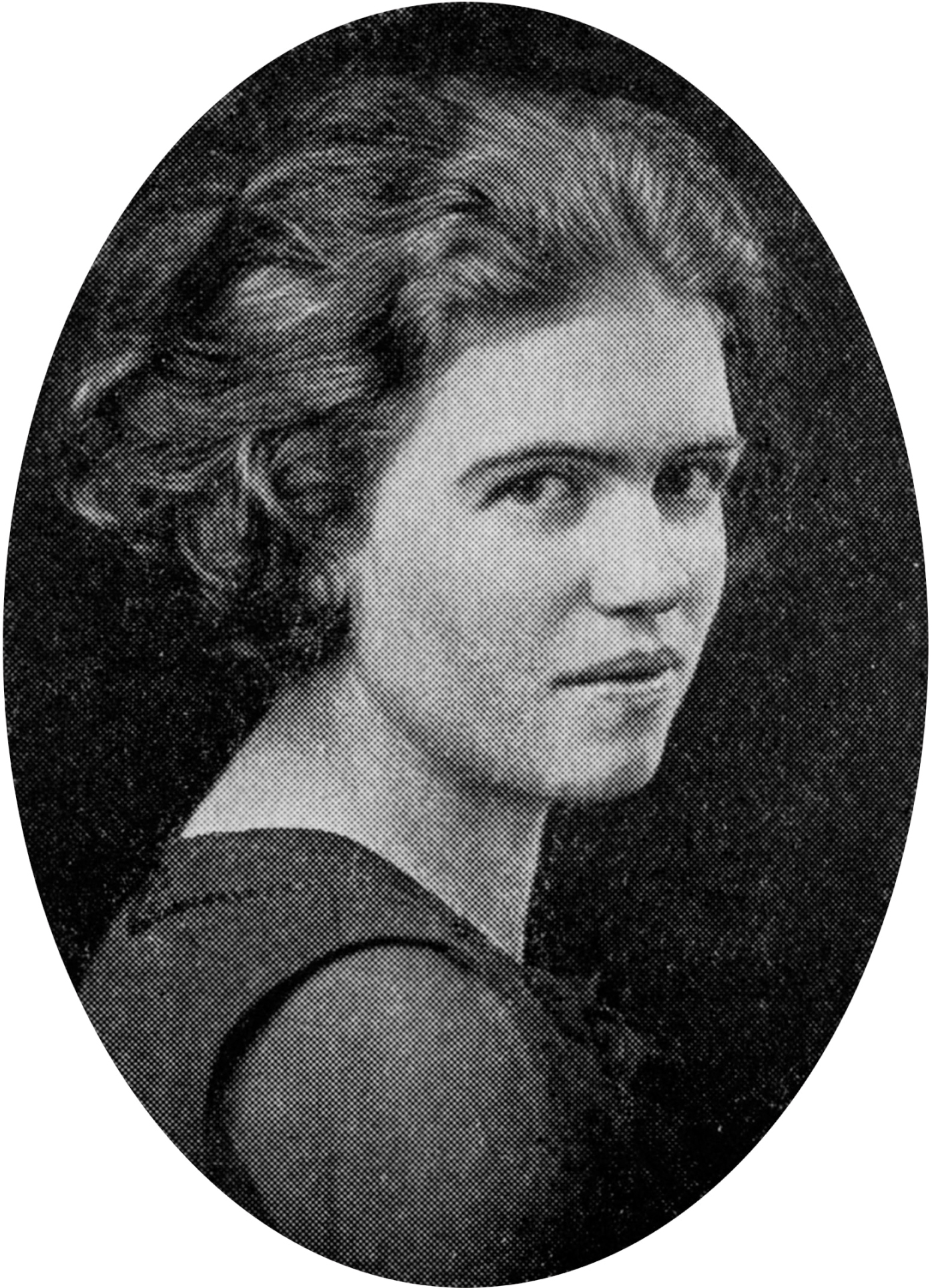

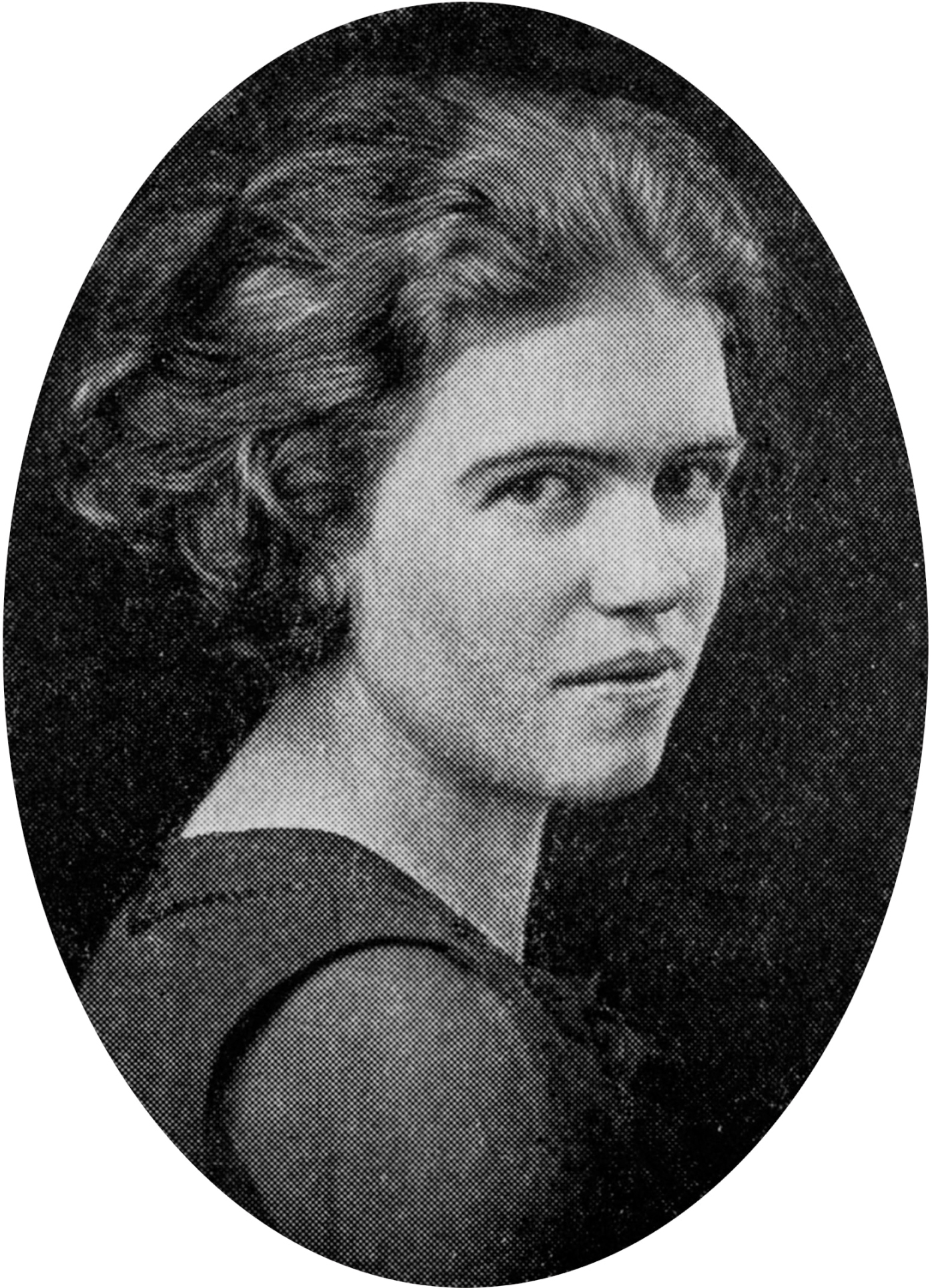

Margaret Mead, senior class photo, from the Barnard College yearbook, 1923.

She was hitching her wagon to a star, and I felt grateful I had never stood in her way.

L UTHER C RESSMAN

August 1925

On the third of August, 1925, a Southern Pacific passenger train streaked across the Arizona desert. Inside the dining car a girl in pale-colored silk sat eating breakfast. Her name was Margaret Mead and she was traveling alone, en route to California, where she was to catch the SS Matsonia, the first of two steamers that would take her to the South Seas.

Known among her friends as extravagantly talkative, Margaret was quiet now, gazing out at scenery that was passing by in a blur. Her mind was full of what had just happened, and what was to come.

Margarets light brown hair, cut short in a bob, was unruly, the bridge of her nose lightly freckled. At just over five-foot-two, and weighing not quite one hundred pounds, she looked more like an eleven-year-old child than a twenty-three-year-old woman. Accustomed to being underestimated, she had long ago decided it didnt matter. As soon as she spoke it was apparent from her Main Line accent and the hint of command in her voice that she was, in reality, a young lady who knew what she was about.

Raised in the privileged environs of Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and recently married to her childhood sweetheart, Margaret had never spent a night alone in her life, yet now she was at the beginning of a journey that would span nine thousand miles. Once she reached her destinationAmerican Samoashe would spend the better part of a year separated from family and friends. Sometimes, though she was loath to admit it, she went numb at the thought.

Breakfast finished, Margaret took out her writing case and began a letter to one of her preferred confidants:

Dear Grandma Ruth left me last night at Williams and in three hours I shall be in Los Angeles and see Uncle Leland, I hope. We had gorgeous weather all the way across the desert, almost cold, even in the day time.

For the last two years Margaret had been working toward her doctorate in anthropology at Columbia University in New York City. When faced with choosing a culture on which to base her professional career, she said she had no intention of being like the rest of the women in the department who were content to study the American Indian. She wanted to go to Polynesia. Nearly everyone she knew had said no, the South Pacific was impossible. Young ladies, traveling on their own, simply did not go there.

Her letter continued:

We saw many Indians baling alfalfa into square blocks, and we marveled that the alfalfa was green. Blue and red and yellow are the colors of this country; green is swallowed up when it does occur. The cattle and horses are lean and lost looking, gaunt and gray on the barren lands. But the trees bloom, Grandma, all of them, pines and junipers and all. Think of a little tree that smells like an evergreen and has daisies on it. And there are also delicate scarlet flowers, growing unexpectedly in the waste land.

Everyone had said the enterprise carried too many risks. Margaret could not speak a word of the native language and the tropics were treacherous. But Margaret was adamant, and stubborn. She prevailed and now, in a mere four weeks, she would begin fieldwork in Samoa to observe the way that adolescent girls in a primitive culture differed from their counterparts in America. It was not for nothing that, as a child, her determination had earned her the nickname Punk. She was also known to be irrepressibly curious.

Ruth and I got different things out of the Grand Canyon, but we both loved it. She was the most impressed by the effort of the river to hide, a torturing need for secrecy which had made it dig its way, century by century, deeper into the face of the earth. The part I loved the best was the endless possibilities of those miles of pinnacled clay, red and white, and fantastic, ever changing their aspect under new shadowing cloud. One minute I saw a castle, with a great white horse of mythical stature, standing tethered by the gate, and further over, a great Roman wall.

Margaret did not realize it, could never have guessed it, but those words that shed just put to paper, the ones that alluded to the endless possibilities before her, were prophetic. That quality she exhibited, the ability to engage with the life around her, to respond to events as they were unfolding and turn the moment to her advantage, was a gift, one she was armed with as she set out to confront the unknown.