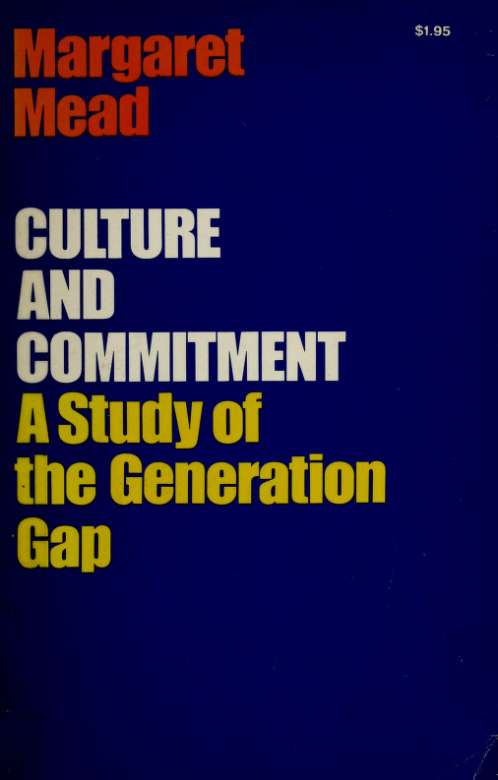

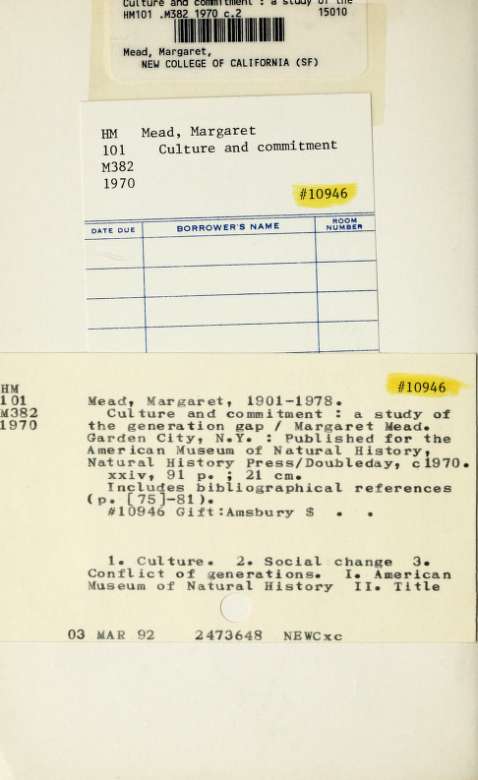

Margaret Mead - Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap

Here you can read online Margaret Mead - Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1970, publisher: The Bodley Head, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap

- Author:

- Publisher:The Bodley Head

- Genre:

- Year:1970

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

To

My father's mother

and

My daughter's daughter

PREFACE

Twenty years ago, as we prepared for the White House Conference on Children, the central problem agitating young people and those who were concerned with them was identity. In the midst of the tremendous changes going on in the world in the period immediately following World War II it was clear that it was becoming harder and harder for any individual then growing up to find his or her place within the conflicting versions of our culture and within the world that was already pressing in upon us through television, even though the world-wide sharing of national tragedy and cosmic adventure was yet to come.

Today, the central problem is commitment: to what past, present, or future can the idealistic young commit themselves? Commitment in this sense would have been a meaningless question to primitive preliterate man. He was what he was: one of his own people, a people who very often used a special name for human beings to describe their own in contrast to all others. He might fail; he might be ejected from his group; he might under extreme circumstances elect to flee; he might, deprived of his land, become a slave on the land of another people; he might in some parts of the world commit suicide out of personal despair or anger. But he could not change his commitment. He was who he wasinalienable, sheltered and fed within the cocoon of custom until his whole being expressed it.

The idea of choice in commitment entered human history when competing styles of life were endowed with new kinds of sanction of religious or political ideology. No longer a matter of minor comparisons between tribes, as civilization developed commitment became a matter of choice between entire systems of thought. In the phrasings of Middle Eastern religions, one system became right, all others wrong; in the gentler words of Asian religions, other systems "provided a different way." It was then that the question: To which do I commit

Xll PREFACE

my life? was raised for the thoughtful in a form that only temporarily disappears when faith and society and culture are temporarily reunited in isolated and barricaded forms in closed religious sects like the Hutteritesor behind iron curtains into which no alien note is permitted to enter.

In this century, with rising insistence and anguish, there is now a new note: Can I commit my life to anything? Is there anything in human cultures as they exist today worth saving, worth committing myself to? We find the suicide of the fortunate and the gifted, the individual who feels no abiding and unquestioning tie with any social form. Just as man is newly faced with the responsibility for not destroying the human race and all living things and for using his accumulated knowledge to build a safe world, so at this moment the individual is freed to stand aside and question, not only his belief in God, his belief in science, or his belief in socialism, but his belief in anything at all.

It is my conviction that in addition to the world conditions that have given rise to this search for new commitment and to this possibility of no commitment at all, we also have new resources for facing our situation, new grounds for commitment. It is to this theme that this book is addressed. It is written in the belief that only as we come to terms with our past and our present is there a future for the oldest and the youngest among us who share the total round.

February 21, 1969

The American Museum of Natural History

New York City

The United States of America

INTRODUCTION

An essential and extraordinary aspect of man's present state is that, at this moment in which we are approaching a worldwide culture and the possibility of becoming fully aware citizens of the world in the late twentieth century, we have simultaneously available to us for the first time examples of the ways men have lived at every period over the last fifty thousand years: primitive hunters and fishermen; people who have only digging sticks to cultivate their meager crops; people living in cities that are still ruled in theocratic and monarchical style; peasants who live as they have lived for a thousand years, encapsulated and walled off from urban cultures; peoples who have lost their ancient and complex cultures to take up simple, crude, proletarian existences in the new; and peoples who have left thousands of years of one kind of culture to enter the modern world, with none of the intervening steps. At the time that a New Guinea native looks at a pile of yams and pronounces them "a lot" because he cannot count them, teams at Cape Kennedy calculate the precise second when an Apollo mission must change its course if it is to orbit around the moon. In Japan, sons in the thirteenth generation of potters who make a special ceremonial pot are still forbidden to touch a potter's wheel or work on other forms of pottery. In some places old women search for herbs and mutter spells to relieve the fears of pregnant girls, while elsewhere research laboratories outline the stages in reproductivity that must each be explored for better contraceptives. Armies of twenty savage men go into the field to take one more victim from a people they have fought for five hundred years, and international assemblies soberly assay the vast destructiveness of nuclear weapons. Some fifty thousand years of our history lie spread out before us, accessible, for this brief moment in time, to our simultaneous inspection. This is a situation that has never occurred before in human

history and, by its very nature, can never occur in this way again. It is because the entire planet is accessible to us that we can know that there are no people anywhere about whom we might know but do not. One mystery has been resolved for us forever as it applies to earth, and future explorations must take place among the planets and the stars. We have the means of reaching all of earth's diverse peoples and we have the concepts that make it possible for us to understand them, and they now share in a world-wide, technologically propagated culture, within which they are able to listen as well as to talk to us. For the one-sided explorations of the early anthropologist who recorded the strange kinship systems of alien peoples, to whom he himself was utterly unintelligible, we now can substitute open-ended conversations, conducted under shared skies, when airplanes fly over the most remote mountains, and primitive people can tune in transistor radios or operate tape recorders in the most remote parts of the world. The past culture of complex civilizations is largely inaccessible to the technologically simplest peoples of the world. They know nothing of three thousand years of Chinese civilization, or of the great civilizations of the Middle East, or of the tradition of Greece and Rome from which modern science has grown. The step from their past to our present is condensed, but they share one world with us, and their desire for all that new technology and new forms of organization can bring, now serves as a common basis for communication.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap»

Look at similar books to Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Culture and Commitment: A Study of the Generation Gap and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.