Table of Contents

Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Hanson, Peter, 1969

The cinema of Generation X: a critical study of films and directors / by Peter Hanson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7864-1334-4

1. Motion picturesUnited StatesHistory. 2. Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Generation X. I. Title.

PN1993.5.U6H34 2002

791.43'75'097309049dc21 2001008469

British Library cataloguing data are available

2002 Peter Hanson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

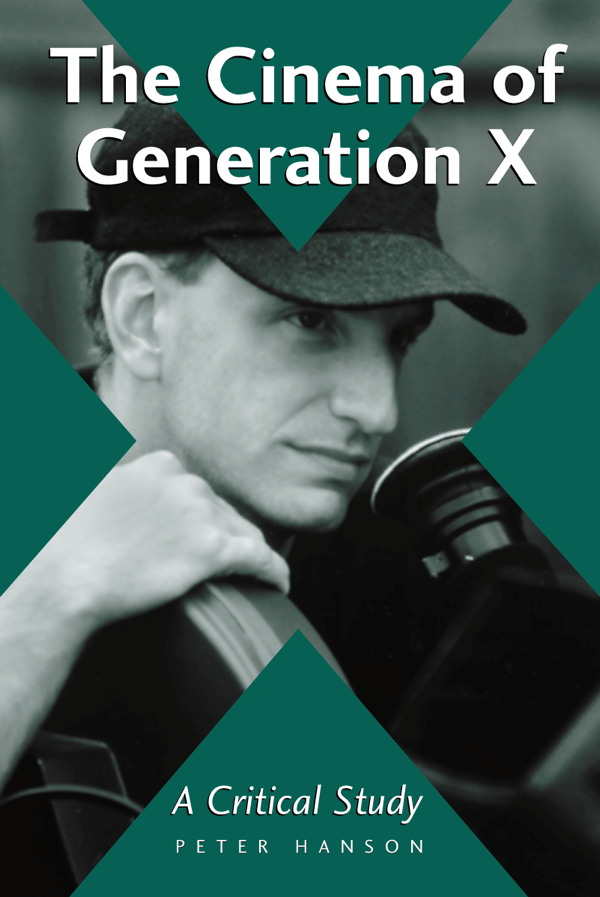

Cover photograph: Steven Soderbergh directing the 2000 film Erin Brockovich

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Acknowledgments

For her patience, support, insight, and clear-headed reactions throughout the various stages of this books development, I am indebted to Leslie S. Connor, to whom this book is dedicated. Thanks also are due to Margaret Eck, Joe Masucci, Frank Mouris, the Clan Swierzewski, Frank Mouris the New York State Archives Partnership Trust, the New York State Writers Institute, and the management of Hoyts Crossgates Cinemas and the Spectrum 7 Theatres, both in Albany, New York.

Preface

Youth isnt always wasted on the young.

Beginning in the late 1980s and continuing through to the present day, a wave of youthful filmmakersworking in modalities ranging from the brazen to the austerehas infused both mainstream and independent American films with the vigor, the promise, the possibility, and even the foolhardiness of youth. And while it sometimes seems there is little order and unity among these wildly diverse artists, one essential fact joins them: They all are members of Generation X.

The tones wrought by Gen-X filmmakers are as varied as the directors themselves: Steven Soderberghs provocative postmodernism, Quentin Tarantinos swaggering violence, Kevin Smiths philosophical ribaldry, David Finchers seductive nihilism. And even individual directors from this unpredictable group have surprises up their sleeve: Soderbergh followed the straightforward drama Erin Brockovich with an experimental examination of Americas war on drugs, Traffic, and a glossy caper film populated by several of Hollywoods biggest stars, Oceans Eleven. Just as no one description captures the entirety of the cinema of Generation X, no one description captures the entirety of an important Gen-X filmmakers body of work.

The reasons why directors born in the 1960s and 1970s are so hard to nail down are many and fascinating, but the enigma of the cinema of Generation X revolves around a few key facts: Gen Xers grew up during one of the most tumultuous periods of American history, were inundated with popular culture to an unprecedented degree, suffered through social changes such as a rash of divorces, and then created a youth culture anchored in irony, apathy, and disenfranchisement. Is it any wonder that the filmmakers who belong to this group send mixed messages?

This book explores how a difficult transition from childhood to maturity colored the sensibilities of Gen Xers who became filmmakers, andfurther details how those sensibilities inform such intriguing Gen-X commonalties as the obsession with pop-culture references, the willingness to embrace postmodern narrative techniques, and the telling aversion to moral absolutes. It says everything about the cinema of Generation X to note that this generation has produced such unconventional movies as sex, lies, and videotape, Pi, Fight Club, and Memento.

Yet Gen Xers also create unthreatening escapism, whether its the superheroic action of X-Men or the supernatural adventure of The Mummy Returns. These pictures, and others like them, are as reflective of the character of Generation X as any others, however, for it follows that a generation raised on shallow popular culture would create their own disposable entertainment given the chance.

The disparities between the serious artists of this generation and their crowd-pleasing counterparts are important, but so too are the instances in which many facets of this peculiar generations identity converge: Consider Larry and Andy Wachowskis The Matrix, a testosterone-laden action movie thats also a mind-bending exploration of whether the concept of reality still holds its meaning in an age defined by technology.

The hero of The Matrix is a definitive Gen-X figure, because like countless members of the generation to which the Wachowksi brothers belong, the hero is overwhelmed by the onslaught of sensation and information and misinformation that is life in the modern world. He is lost, and only others like him can help him find his way. Not all Gen Xers are lost, of course, but nearly all Gen-X filmmakers are on a quest not unlike that pursued by the hero of The Matrix. They want to make sense of a senseless world.

To understand how these directors use their work to further this quest is to gain insight into the collective soul of a generation, and to more deeply understand why the cinematic creations of that generation are far more than just movies. Taken together, they provide an illuminating interpretation of the culture in which we live.

1

The Arrival

In the last summer-movie orgy of the 1980s, Hollywoods propensity for high concepts and higher budgets reached an apex that epitomized the excesses of Greed Decade blockbusters, but also redefined the earning potential of such films. On June 23, 1989, months of savvy advertising and priceless word-of-mouth helped give the superhero adventure Batman a monstrous opening weekend, underlining mainstream Hollywoods ability to spin a masterful marketing campaign around a simplistic, youth-oriented idea.

Although critics were almost universally enthusiastic about the pictures state-of-the-art visuals and the appeal of director Tim Burtons dark wit, the movies hackneyed story left all but the most undemanding viewers disappointed. So for observers who had lamented the steady evolution of the action-oriented blockbuster since Steven Spielbergs Jaws and George Lucass Star Wars earned unheard-of revenues in the mid1970s, the record-setting conquest of Batman was a nail in the grave of quality cinema. After all, Batman was merely the victor in a high-concept sweepstakes whose other entrants included Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, the third installment in Spielbergs nostalgic adventure series; Ghostbusters II, a follow-up to the popular supernatural comedy starring Bill Murray; Honey, I Shrunk the Kids, a Disney-produced family adventure with a science-fiction premise; and The Abyss, director James Camerons epic underwater drama.

Before the summer of 1989 drew to a close, however, a film hit theaters that had neither a high concept nor easily marketable youth appeal. The picture was psychological and erotic, making it a distinct alternative to the simple-minded, neutered entertainment of the years blockbusters. And while the summers big flicks all had some form of brand-name appealthe Batman character had been popular, in various mediums, since before World War II; Indiana Jones and Ghostbusters were sequels; and so onthe dark-horse movie that opened on August 2 was the first-time directorial effort of a little-known film editor, and it was released by a New York Citybased boutique distributor best known for bringing European pictures to America. The movies meatiest credentials, in fact, were a Palme dOr prize from the Cannes Film Festival and a warm reception at the Sundance Film Festival. It hardly had the makings of a pop-culture sensation.

Next page