Table of Contents

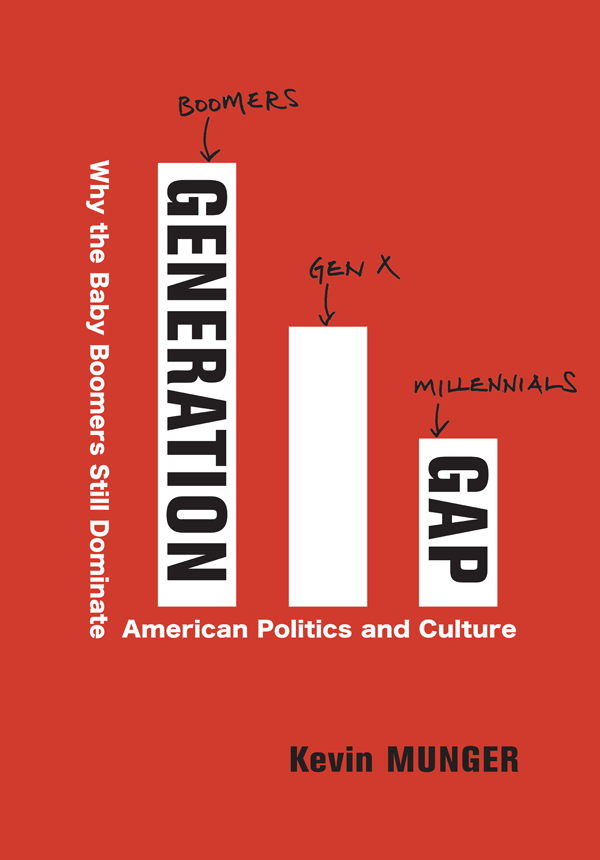

Generation Gap

Generation Gap

Why the Baby Boomers Still Dominate American Politics and Culture

Kevin Munger

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2022 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

EISBN 978-0-231-55381-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Munger, Kevin M., author.

Title: Generation gap: why the baby boomers still dominate American politics and

culture / Kevin Munger.

Description: New York: Columbia University Press, [2022] | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021053382 (print) | LCCN 2021053383 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780231200868 (hardback) | ISBN 9780231200875 (trade paperback) |

ISBN 9780231553810 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Baby boom generationPolitical activityUnited States. |

Baby boom generationUnited StatesInfluence. | Older peoplePolitical activity

United States. | Conflict of generationsPolitical aspectsUnited States. |

Political sociologyUnited States. | Cohort analysis. | United StatesPolitics and

government.

Classification: LCC HQ1064.U5 M836 2022 (print) | LCC HQ1064.U5 (ebook) |

DDC 305.2dc23/eng/20220110

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053382

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053383

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Chang Jae Lee

Contents

T he American dream is that our children will enjoy better lives than we did; the modern world is built on this idea of progress. The metaphor of government-as-parent does not always work, but there are important parallels between progress at the level of the generation-as-family-unit and progress at the level of generation-as-contemporaneous-citizens. Governments of all stripes justify their good governance by delivering economic growth and raising standards of living.

But this progress has come with serious costs. We have exploited the resources and labor of other countries and pillaged the environment. Regardless of whether any of that was worth it, it seems the consensus now is that all the nations of the world can achieve Western prosperity if they adopt the correct institutions and the most modern technology.

There is a branch of social science that we might broadly call liberal positivism. Its central aim has been to understand what these institutions are that bring prosperity. When Adam Smith titled his most famous work An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, he meant it.

From the outset, however, even a social scientist of Smiths caliber could not simply impose the ideal institutions on a nation. Many obstacles, not least the biological realities of humanity, get in the way.

In his 1928 essay The Problem of Generations, the German sociologist Karl Mannheim wrote about how Smiths contemporary David Hume first drew the connection between governments and people: Only because mankind is how it isgeneration following generation in a continuous stream, so that whenever one person dies off another is born to replace himdo we find it necessary to preserve the continuity of our forms of government. Hume translates the principle of political continuity into the biological continuity of generations.

The Problem of Generations

Mannheims essay anticipated the central ontological conflict, that of generations, in the contemporary United States. He describes two broad epistemic approaches to understanding generations: the positivist and the historical romanticist.

The positivist approach is concerned with numbers and patterns. It seeks a science of generational development and displacement. Auguste Comte, the father of positivism, was partly motivated by a desire to model the tempo of human progress using the mathematics of generations. Mannheim argues that generational analysis is an ideal starting place for the positivist: There is life and death; a definite, measurable span of life; generation follows generation at regular intervals. Here, thinks the Positivist, is the framework of human destiny in comprehensible, even measurable form. All other data are conditioned within the process of life itself. Despite the neat structure of generational data, contemporary social science has paid little attention to generations. Part of the explanation may be the explosion of other kinds of data with the rise of computation. The discovery of some thorny statistical challenges in the 1970s may have discouraged positivist researchers. Or perhaps the progressive humanism that predominates among social scientists has blinkered them in its insistence on the fundamental equality of all humans. This moral premise has been a powerful remedy to the essentialist tendencies of social scientific positivism. The uncritical reification of what can be easily measured left a shameful legacy of scientific racism.

But the simple fact is that there is no fundamental equality among humans at any given time, even if there is fundamental equality in expectation, or averaged across the life cycle. We fully acknowledge this inequality when it comes to minors, establishing strict laws and rules designed to protect these humans who clearly need protecting. It is also true that people change continuously throughout their lives, in ways that are relevant to social science. The age composition of a country has huge effects on its economy, politics, and culture. And the age composition of a country rarely changes quickly, making this line of inquiry uninteresting for social scientists aiming for policy impact.

The contemporary appeal of generational analysis to the romantic-historical social scientist is more obvious. We share our experience of the world with people who share our experiences. Events crystallize this phenomenonWhere were you on 9/11?but the accumulation of the everyday is more profound. There is a unity that comes with generational identification, a capacity to reject what came before and to dream of what is possible.

Mannheim cites the philosopher Martin Heidegger, who wrote that The inescapable fate of living in and with ones generation completes the full drama of individual human existence. A beautiful turn of phrase, but consider Heideggers context. He was born the same year as Hitler, and he never opposed Nazism. Romantic-historical generational unity enables the construction of the Other in other generations. We are the center of action. Older generations are in our way, and younger generations are pitifully unable to function in the world we created.

Like Mannheim, we can synthesize these two approaches. The positivist constrains the excesses of the historical romanticist with data. And when the positivist has no data, the romanticist can offer the experiences of people living in their generation.

Most political science works in the positivist mode. The primary method of this book is to combine a wealth of historical data with novel survey evidence. These surveys attempt to understand the experiences of the surveyed in more qualitative terms, a stepping stone bridging our data and the romantic self-perceptions of people as members of generations.