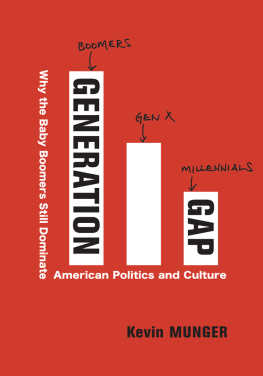

The precise definition of a baby boomer is disputed, but I have defined it as anyone born between 1945 and 1955. David Willetts in his book The Pinch defines it very differently, as people born between 1945 and 1965, but he is quite wrong, because this period contains not one but two baby booms, separated by a small slump. The classic baby boomers , born between 1945 and 1955, were a completely different sort of generation from those born at the start of the sixties.

The complaint may be made that I have not written an objective history of the sixties, but have selected those events and quotes that bear out my thesis. I have a ready answer to this, which is: yup, thats what Ive done.

I have told the story of the baby boomer generation partly through the lives of individuals. Among many others, I have made use of the lives of the only two baby boomer Prime Ministers Britain has ever had, or is ever likely to have, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown; of the singer Marianne Faithfull, whose autobiography Faithfull is full of insights into what the children of the sixties thought they were, and what they really were; of the student-Trotskyist-turned-far-right-commentator Peter Hitchens and of Paul Mackney, student Trotskyist who kept the faith and became an important and successful trade union leader; and of Greg Dyke, representing that part of the baby boomer generation which made a fortune in business, in a peculiarly sixties way. Im particularly grateful to three of them Greg Dyke, Peter Hitchens and Paul Mackney for long and illuminating interviews; and to Gordon Brown for an interview while I was writing his biography, which has helped me here too.

Other baby boomers make occasional appearances, and some of them have been kind enough to read and comment on certain passages and chapters, or to help with information. They include Eddie Barrett and Tony Russell, who between them or so it seems to me know everything there is to know about popular music (and this book was completed in Eddie Barretts charming house in Calabria, looking out at islands and mountains). They also include the playwright Steve Gooch, and old university friends who were especially helpful on 1968: Mike Brereton, Malcolm Clarke, Marshall Colman, John Howkins, Marina Lewycka, Linden West and Martin Yarnit.

I also want to thank the readers of U3A News, the magazine of the University of the Third Age, and the best place in the world for anyone writing about events in the last fifty years or so to find people who will remember them.

Among the generation betrayed by the baby boomers, I would like to thank in particular two Leeds University graduates in their twenties for information and insights: my son Peter Beckett, now a political lobbyist , and the former National Union of Students president Kat Fletcher.

The baby boomers saw themselves as pioneers of a new world freer, fresher, fairer and infinitely more fun. But they were wrong. The world they made for their children to live in is a far harsher one than the world they inherited.

The first of the men and women born in the baby boom that followed the Second World War started to come of age in the radical sixties . Not since 1918 had the young talked serious revolutionary politics as they did in the sixties.

But in 1918, the men who came back from the war knew that the world was amiss, and knew what they wanted to do about it. So when at last the generation that fought the First World War came to power, in 1945 under Major Clement Attlee, they changed the world. The 1942 Beveridge Report had called for the abolition of the five giants Want, Ignorance, Disease, Squalor and Idleness and between 1945 and 1951, despite a war-ruined economy, the Attlee government set about a systematic and remarkably successful assault on those evils.

Exactly fifty years later, revolutionary talk was heard across the land again. But the generation of 1968 was not at all like the generation of 1918. Sixties radicalism decayed fast. It decayed, not because it was groundless, but because it was not grounded. What began as the most radical-sounding generation for half a century turned into a random collection of youthful style gurus who thought the revolution was about fashion; sharp-toothed entrepreneurs and management consultants who believed revolution meant new ways of selling things; and Thatcherites, who thought freedom meant free markets, not free people. At last it decayed into New Labour, which had no idea what either revolution or freedom meant, but rather liked the sound of the words.

The sixties really began in 1956 with John Osbornes Look Back in Anger, but few people noticed until the Beatles released Love Me Do in October 1962. By then the oldest of the baby boomers were fully seventeen years old, and within three years they were to know everything there was to know, from the secrets of the universe to the correct way to roll a joint.

The short sixties from the release of Love Me Do to the student sit-ins and the Paris vnements of summer 1968 was a wonderful time to be young. People took the young seriously for the first time, which was good. But the young took themselves seriously, which was less good. The young thought New Jerusalem was round the corner, its arrival hindered only by the conservatism of Harold Wilsons Labour government. They did not realise that they were living in New Jerusalem; that it would all be downhill from then on; and that their generation, which benefited from this dazzling array of freedoms, would, within twenty years, destroy them.

Nor did they realise for they had never heard of Tony Blair how lucky they were to have Wilson to hate. Without Wilson, the baby boomers might well have had to fight and die in Vietnam, for a lesser Prime Minister could have been cowed by President Lyndon Johnson and Americas power to cripple Britains economy.

For the first time since the Second World War, there was money, there was safe sex, there was freedom, and no one bothered to stop and think with what misery these things had been bought by earlier generations , for the baby boomers rather despised the past, a small faraway country of which they knew little. Most of the baby boomers hardly realised the privations of their parents, and the struggle that had taken place to ensure that they were not equally deprived.

Before the First World War, 163 of every 1,000 children died before their first birthday. The figure was twice as high for working-class children . It is 15 per 1,000 today. Of those children that survived, a quarter did not live beyond the age of four. In the early weeks of the National Health Service in 1948, consultants reported shoals of women coming in with internal organs that had been prolapsed for years, and men with long undiagnosed hernias and lung diseases.

In the thirties, my grandmother, widowed by the First World War, kept a tin on a shelf, into which she put every spare coin she could, against the day when one of her children might need the doctor. She was a rather wise old lady, so I felt a sense of shock when, as a teenager, I received a letter from her, and realised she wrote like a five-year-old. Like millions of her generation, she was never taught to write properly.

Working-class children in the thirties seldom had enough to eat and received just enough education to equip them for routine work. A father out of work meant a family near starvation. My parents assumed that a working-class child was smaller than a middle-class child, for want of good food. Most of our parents came out of the Second World War determined to change all that.

And that is why the Attlee settlement of 194551 gave working people leisure, healthcare, education and security for the first time. In the fifties, older children, especially those at work, had disposable income. Young people became, for the first time, serious consumers, able to make choices and support those choices with cash.