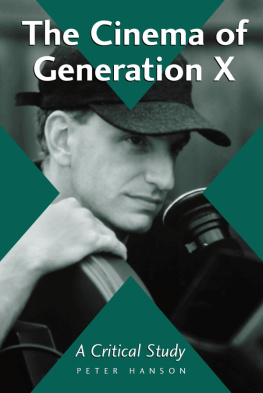

Images for a Generation Doomed

Images for a Generation Doomed

The Films and Career of

Gregg Araki

KYLO-PATRICK R. HART

Published by Lexington Books

A division of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.lexingtonbooks.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2010 by Lexington Books

First paperback edition 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The hardback edition of this book was previously cataloged at the Library of Congress as follows:

Images for a generation doomed : the films and career of Gregg Araki / Kylo-Patrick R. Hart.

p. cm.

Includes filmography.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Araki, GreggCriticism and interpretation. I. Hart, Kylo-Patrick R. II. Title.

PN1998.3.A65H37 2009

791.430233092dc22

2009033981

ISBN: 978-0-7391-3997-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-7391-3998-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-7391-3999-8 (electronic)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For A, E, I, O, U, and Z3

Contents

Preface

The first time I viewed The Doom Generation, Gregg Arakis 1995 film, I absolutely hated it. I stumbled upon it during my early years of doctoral study at the University of Michigan, while supporting myself by managing a video store on the weekends, and because I found its cover-box text and images to be so intriguing, I ended up taking it home. As I watched it, I found its narrative to be a bit too fractured and surreal, its dialogue to be a bit too evidently scripted and pretentious, its characters to be a bit too lackluster and stereotypical, and its entirely unexpected, extremely brutal concluding bloodbath to be unnecessarily shocking rather than truly compelling. As its closing credits (thankfully!) started to roll, I immediately classified the work in my mind as a leading example of cinematic trash and went on with my everyday life.

In the days following that first viewing experience, however, I could not get Arakis filmits sexually charged narrative developments, its most amusingly noteworthy lines of dialogue, the angst-filled interactions among its central characters, and particularly its blood-soaked endingout of my mind. As I reflected further on both its manifest and latent contents, I started to appreciate the way that the works rawness, aggressive energy, and treatment of nihilistic plot developments and themes substantially challenge hegemonic conceptions of ideology and social order as well as repressive sexual and gender roles. I began to realize that Arakis use of film grammar to convey a gay sensibility and his reworking of established genre expectations to serve queer storytelling goals rendered the film potentially quite subversive. Less than a week after I had initially encountered the film, it dawned on me clearly that The Doom Generation isnt really cinematic trash after all, even though it may look that way on its surface. Instead, it actually communicates a powerful, sobering message about the threats of religious and social conservatism to the well-being of all individuals who can be regarded as deviant in any way from the hegemonic mainstream status quo. As a result, I ended up watching the film again (and again, and then again), and it has since become one of my all-time favorite films.

My newfound enthusiasm for the cultural treasure that is The Doom Generation motivated me to seek out and view Arakis other films. While writing my book The AIDS Movie: Representing a Pandemic in Film and Television, I got to know the contents of Arakis AIDS road movie, The Living End (1992), quite intimately, and I found it to offer a unique brand of realism with regard to the cinematic exploration of the lives of contemporary queer individuals and people with HIV/AIDS as well as provocative onscreen images of romantic and sexual relationships that border at times on the pornographic. I appreciated the way that Totally F***ed Up (1993), with its focus on the search for happiness and meaning in their everyday lives by a small group of gay and lesbian teens, continued to foreground a variety of human sexualities and sexual practices that have historically been marginalized by mainstream society and rarely encountered in U.S. cinema. I found Nowhere (1997), Arakis seemingly hallucinogenic exploration into the realities of life as experienced by contemporary teens of various sexual orientations, to offer a more playful, hormonally charged, and eye-candy-filled viewing experience (even though I found its concluding sequence to be frustrating and entirely unfulfilling). I looked forward with enthusiasm to seeing what the directors future cinematic offerings would be.

During my first year as a new assistant professor, at the start of the new millennium, I decided to teach a course on auteur film directors. Given my appreciation of his unique storytelling approaches and his penchant for exploring (potentially) controversial subject matter and non-heterosexual themes in boundary-pushing ways, I chose, in addition to Ingmar Bergman and other widely revered auteurs, to include Gregg Araki as one of our subjects of study. Because I only had enough time available for the students to view and discuss three Araki films, my plan was for them to analyze The Living End, The Doom Generation, and Nowhere. However, just prior to the week during which we were to analyze Nowhere, I learned that Arakis subsequent film, Splendor (1999), about two young men and one young woman who enter into a mnage--trois living arrangement, had been released on DVD. I immediately ordered a copy, which arrived on the day of our class meeting. As a result, I did not have an opportunity to view its contents in advance of walking into the classroom. I then gave my students a choice: to view and discuss Nowhere as originally planned, or to instead view and discuss Splendor, with the express disclaimer that I had not yet personally seen it, so I had no idea what sorts of (potentially extreme) Arakian imagery and plot developments it might contain. The students opted for Splendor and I sat back, a bit apprehensively, to view it along with them, fearing what instances of explicit dialogue or violent and sexual acts it might contain. To all of our surprise (and, quite frankly, subsequent disappointment), the contents of Splendor were far more tame than any of us ever imagined they would betwo attractive guys and a similarly attractive young woman living together, sleeping together in the same bed, and having sex in that bed and nothing at all happens between the two guys? Theres not even any romantic or sexual attraction evident between the two men at any point in the film?

When all was said and done, Splendor

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.