The Cinema of John Boorman

Brian Hoyle

THE SCARECROW PRESS, INC.

Lanham Toronto Plymouth, UK

2012

Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

10 Thornbury Road, Plymouth PL6 7PP, United Kingdom

Copyright 2012 by Brian Hoyle

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hoyle, Brian, 1979

The cinema of John Boorman / Brian Hoyle.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8108-8395-6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8108-8396-3 (electronic)

1. Boorman, John, 1933 . 2. Criticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PN1998.3.B665H69 2012

791.4302'33092dc23

2012015538

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For my family, of every generation and species, on both sides

of the Atlanticand especially for Beaumont and Hectoryou

are sorely missed.

Acknowledgments

Like making a film, writing a book like this is not an individual effort, and there are a good many people and institutions to thank.

First I must acknowledge the generous support of the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, who funded research trips to the British and Irish Film Institute archives.

Thanks also to the BBC and the BFI, and to Kathleen Dickson at the BFIs Viewing Centre, for making Boormans early BBC films available for me to watch. Thanks also to Scott Frank, co-producer of Two Nudes Bathing, for providing a copy of the film.

A special mention must also go to Nathalie Morris, Jonny Davies, and Emma Furderer in Special Collections at the BFI in London; Rebecca Grant and Kasandra OConnell at the IFI in Dublin; Monica Thapar at the BBCs Paper Archives; and Fiona Liddell and all the staff at the BBFC archives for their invaluable help locating primary material. Also, my thanks to Ina Preschner at Archiv Darstellende Kunst for being such a great help with the George Tabori papers, and to Barbara Hall at the Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles for answering so many questions and always being so constructive.

The following colleagues also provided invaluable feedback, encouragement, and support during the course of this project: Professor Rowland Wymer at Anglia Ruskin; Professor Greg Walker at the University of Edinburgh; Dr. Alan Fletcher at University College Dublin; Dr. Peter Kramer at the University of East Anglia; and Professor Christine Geraghty and Dr. Chris Gair at the University of Glasgow. Particular thanks also to Professor Charles Barr for all his kind advice and for bringing Six Days to Saturday to my attention.

My heartfelt gratitude goes to my colleagues at the University of Dundee, especially Professors Peter Kitson and Nicholas Davey, Dr. Keith Williams, and Matthew Jarron in Museum Services; Alice Black at Dundee Contemporary Arts; and Elizabeth, Q., Cassia, Theo, Jane, and Gerald for all their hospitality in London. (Rest in peace, Gerald.) Most of all, thanks to Dr. Chris Murray for listening to my theories and helping to establish the (still unofficial) center for Lee Marvin Studies, Jodi-Anne George for all the proofreading and putting up with me and helping me make sense of Excalibur. Finally, thanks to those students who did not seem to mind me talking about Boorman all the time (or hid their boredom very well), and to Stephen Ryan, my editor, for his infinite patience.

Last but certainly not least, I would like to thank John Boorman, whose films have given me so much pleasure, some pain, and a lot to think about.

Introduction

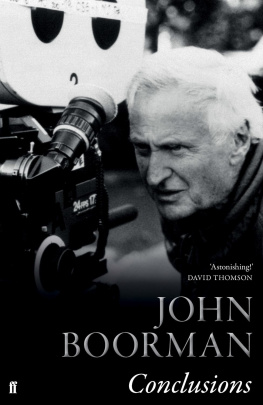

John Boormans career, which has spanned five decades and sixteen feature films, has been one of unusually precipitous ups and downs. Described as a major, if erratic, talent, His is also a career of great breadth. Over the years his work has straddled swinging London, New Hollywood Cinema, European art cinema, the rise of the blockbuster, the British film renaissance of the 1980s, and the emergence of an insipient Irish film industry.

Despite lapses in quality and changes of context, each of his films clearly bears his signature. Indeed, he has been heralded as a rare instance of a genuine British auteur. However, it is almost impossible to place him within the context of any national cinema. Several of the qualities that link his filmsa fascination with myths and dreams, an underlying romanticism, and stylized visualsalso set them apart from the dominant realist mode of British filmmaking. Yet, despite an early emigration to Hollywood, he has not found a home there either and he remains content to be seen as an international figure who wanders between large-scale American films and more intimate ones made in Britain or Ireland, where he has lived since the 1970s.

Boorman also has a reputation for working in far-flung locations, often under strenuous conditions. To date, he has made films on five continents. This is indicative of the filmmakers fascination with quests. Indeed, were one to identify a single thread running through Boormans career, this would be it. In the vast majority of his films his characters seek out some sort of metaphorical grail, sometimes unobtainable but often to be found lurking within the protagonists psyches. Likewise, his career can be viewed as a kind of quest. He spent his first two decades as a director preparing to make a film about the Arthurian legends, which have always been central to his work, and he is forever searching for what he calls the elusive grail, a film that transcends film. Indeed, Boorman has a slightly perverse streak that stops him from taking his work entirely seriously. For example, Excalibur (1981), his Arthurian epic, is, depending on ones view, either leavened or undermined by several idiosyncratic touches, not least of which is the semi-comic portrayal of Merlin. Conversely, this same perversity has caused him to approach lighter material in an oddly weighty fashion, as when he turned a vehicle for the pop group the Dave Clark Five into a somber road movie and imbued a family comedy for Disney with an anti-materialist message and countless references to French painting.

It is also difficult to isolate trends in Boormans work, and any generalization can quickly be met with an example to counter it. For instance, David Thompson has argued that Boorman provides his best results within recognizable genres, but also claims that the spy-thriller The Tailor of Panama (2001), which is one of his more straightforward genre films, is one of his worst. yet several of his finest films are the most grounded in realism. One could go on, but the point is well made: Boorman is erratic to a fault.

Despite, or perhaps because of all this, critical writing on his complete oeuvre is rather thin on the ground and has mostly come from continental Europe, where Boorman enjoys something of a higher reputation. The first volume to attempt a survey of his complete career was written in Italian by Adriano Piccardi and published in 1982, shortly after

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.