John Hill 2011

All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 610 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in 2011 by

PALGRAVE MACMILLAN

on behalf of the

BRITISH FILM INSTITUTE

21 Stephen Street, London W1T 1LN

Theres more to discover about film and television through the BFI. Our world-renowned archive, cinemas, festivals, films, publications and learning resources are here to inspire you.

Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

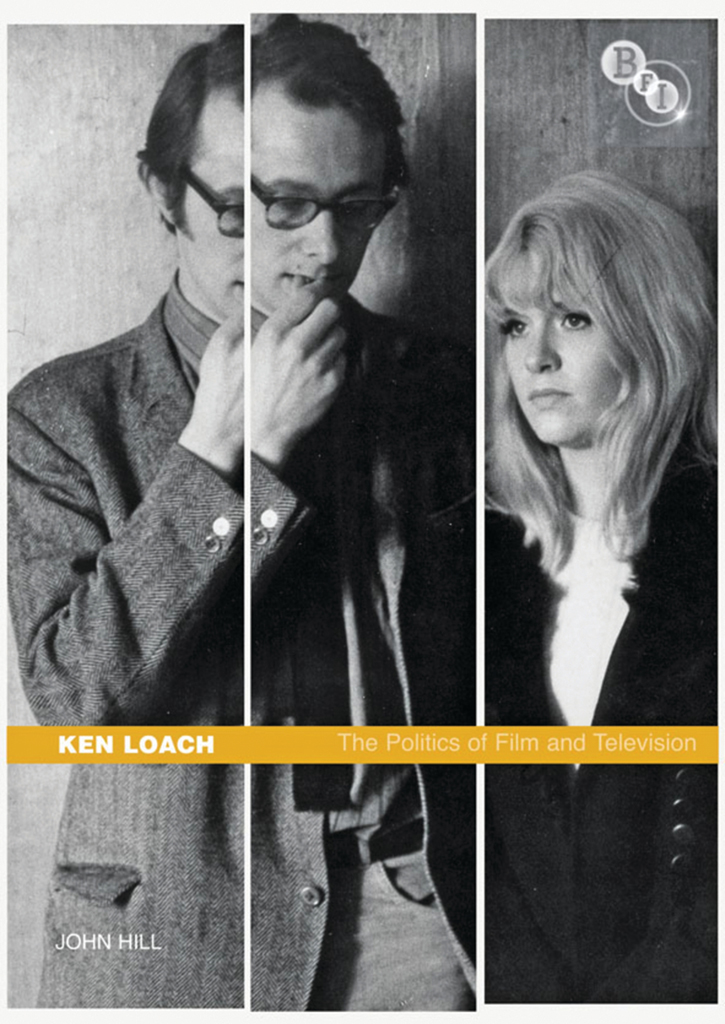

Cover design: couch

Cover image: Ken Loach with Carol White on the set of Poor Cow (Ken Loach, 1967), Fenchurch Films Ltd

Designed by couch

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

ISBN 978-1-84457-203-8 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-84457-202-1 (hbk)

eISBN 978-1-83871-659-2

ePDF 978-1-34992-473-8

Contents

I am indebted to a range of people who have contributed to the research and writing of this book over a period of years. My interest in Loach was revived by being asked to write on his work by a number of editors: Mark Robinson (Circa), George McKnight (Agent of Challenge and Defiance: The Films of Ken Loach) and Leslie Felperin (Sight and Sound). My contribution to Sight and Sound led Andrew Lockett to propose a book on the topic for BFI Publishing. The project was then taken over by Rebecca Barden at BFI/Palgrave Macmillan and I am grateful to her for both her support and patience. Her colleague Sophia Contento has also been most helpful and efficient in seeing the book through to production. I am particularly grateful to Royal Holloway, University of London, for allowing me a period of leave to work on the project and to the ARHC (Arts and Humanities Research Council) for providing matching funding. The research and writing of the book began while I was still at the University of Ulster and I am grateful to the University for some initial funding.

I am, of course, grateful to Ken Loach himself for agreeing to be interviewed and to Eimhear McMahon of Sixteen Films for her help in locating material. I would also like to thank the Foyle Film Festival, Sources 2 and the Short Ends World Film Schools Festival for inviting me to interview Loach on stage. Tony Garnett and Ken Trodd have also been very helpful in providing additional information on Loach and Jim Allen. I have also received excellent assistance from Trish Hayes and Jeff Walden at the BBC Written Archives Centre in Caversham and from staff at the British Film Institute Library in London. Kathleen Dickson and Steve Tollervey of the BFI were also very helpful in setting up screenings for me while both the Irish Film Institute and the UK Film Council assisted with the location of cuttings. I am also indebted to Ian Christie, Lez Cooke, Michael Gold, Ian Greaves, Jacob Leigh, Julian Petley, David Steele and Rob Turnock for making other material available to me. Kelly Davidson also provided research support at an early stage of the project.

Pamela Church Gibson and Noel McLaughlin contributed helpful comments on various chapters while various friends and colleagues Deniz Bayrakdar, Charlotte Brunsdon, Susanna Capon, John Corner, Phillip Drummond, Mika Ko, Martin McLoone and Laura Mulvey have offered encouragement and valuable insights.

My father, Rowan Hill, died during the writing of this book and the book is dedicated to his memory.

Ken Loach is a national treasure, observed the Irish Times on the occasion of the release of The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006). It just seems that the nation that produced him is not always keen to treasure him. reveals, the audiences for Loachs films in mainland Europe are now substantially larger than they are in the UK.

It is not too difficult to explain why Loach is regarded with such mixed emotions in his own country. For since the mid-1960s, Loach has not only been one of Englands most active film-makers but also one of its most consistently political. Radicalised, like many of his generation, during the 1960s, he has remained committed to socialist politics throughout the ensuing decades, continuing to draw attention in his films to the shortcomings of contemporary economic and social arrangements while maintaining the possibility that there might be political alternatives. As a result, his film and television work has consistently sought to challenge prevailing political orthodoxies by giving vent to views and attitudes that are often discounted, or marginalised, within the mainstream media. This has not only made him unpopular with commentators of different political persuasions but has also led to objections that he is primarily a polemicist who places politics ahead of both art and entertainment.

As a result, it has become a feature of certain kinds of writing on Loach to discount his politics and claim that, despite the noise his politics creates, Loach should nonetheless be regarded as a great humanist or realist film-maker. While this may be a legitimate critical manoeuvre, it also seems to involve a degree of disregard for and possibly a sense of superiority to the ideas that have animated Loachs work for so long. Certainly Loach himself has expressed continuing exasperation with critics who dwell on the style and technique of his films while paying relatively little attention to their subject-matter. Rather, the book aims to offer a form of social history that locates Loachs film and television productions in a range of political, institutional and artistic contexts and attempts to assess the political significance of his work in relation to these.

This also means that, while the focus of the study may be Loachs work, it is not Loach alone. As Loach himself has readily acknowledged, film and television production is not a solitary activity but involves acts of collaboration. As his former producer, Tony Garnett, commented, when discussing their work together, [f]ilm making is not like writing a novel, it is a social activity and if you look at the films we have been involved in its very difficult to ascribe the credit or blame that easily, in terms of one individual. indicates, the break-up of the mens partnership coincided with a degree of downturn in Loachs fortunes and it was not until Loach established relationships with new producers first Sally Hibbin and then Rebecca OBrien that his career properly revived.