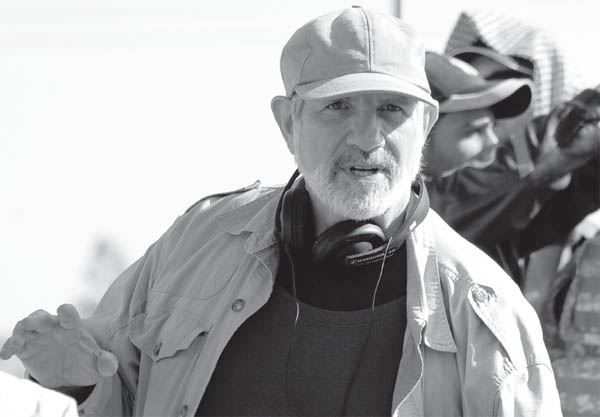

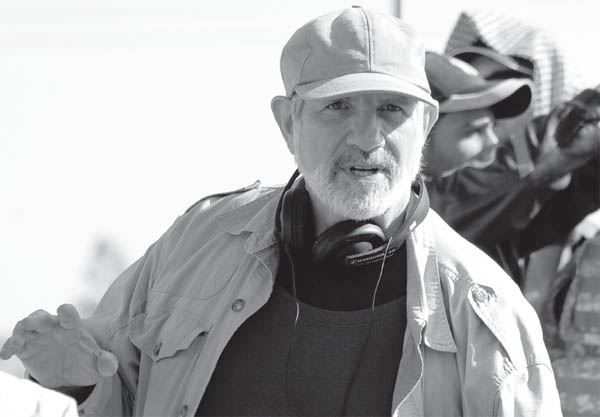

Brian De Palmas Split-Screen

BRIAN DE PALMAS SPLIT-SCREEN

A Life in Film

Douglas Keesey

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2015 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2015

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Keesey, Douglas.

Brian De Palmas split-screen : a life in film / Douglas Keesey.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62846-697-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-62846-698-0 (ebook) 1. De Palma, BrianCriticism and interpretation. I. Title.

PN1998.3.D4K44 2015

791.430233092dc23

2014045130

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

For Helen,

the one love whod sing my song

SPOILER ALERT: Viewers who would like to avoid spoilers are advised to see the films first before reading this book.

Contents

Brian De Palmas Split-Screen

Introduction

Brian De Palma has directed twenty-nine feature films over the last five decades. His movies have been among the biggest successes (The Untouchables, Mission: Impossible) and the most high-profile failures (The Bonfire of the Vanities) in Hollywood history. De Palmas films have helped launch the careers of such actors as Robert De Niro, John Travolta, and Sissy Spacek (who was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actress in Carrie). Quentin Tarantino has named Blow Out as one of his top three favorite films, Dressed to Kill, which was picketed by feminists protesting its depictions of violence against women, helped to create the erotic thriller and slasher horror genres, of which De Palmas own Body Doublewith its driller-killer sceneis perhaps the most notorious example. Scarface, with its chainsaw sequence pushing the edge of permissible on-screen violence, embroiled De Palma in legendary battles with the MPAA over censorship. The fact that gangsta rappers have since made Scarface into a cult film has only added to its controversy.

Over the years, De Palma has also built up a devoted following of film aficionados and criticsmost notably Pauline Kael and Armond Whitewho appreciate his more personal films (Blow Out, Casualties of War, Snake Eyes) for their emotional power and their innovative techniques. The prestigious film journal Cahiers du Cinma voted Carlitos Way the best film made during the entire decade of the 1990s. And in the twenty-first century, De Palma has continued to experiment with new filmic forms, incorporating elements from video games (Femme Fatale), tabloid journalism (The Black Dahlia), and YouTube and Skype (Redacted, Passion) into his latest works.

Of all the trademark techniques for which De Palmas films have become known (slow motion, high angles, long takes, 360-degree pans), there is one that is more closely associated with him than with any other director: the

One of De Palmas most striking uses of the split-screen technique occurs in Carries prom scene where the title heroine wreaks a fiery revenge on all those who have done her wrong. (She looks at them, using her telekinetic powers, and they die in horrible ways.) Does this technique reinforce our identification with Carrie and her righteous anger, or does it distance us from her and cause us to critically examine her actions? Does the split-screen (Carries face on one side and the victims she sees on the other) link us to Carrie, as in a Hitchcockian point-of-view shot, or does the obtrusiveness of such a technique break our link with her, as in a Godardian alienation effect?

I use split-screen as a figure for the stark divisions within De Palma and his works. Four of these divisions are followed as thematic threads running throughout the bookthe key contrasts to which I will keep returning. These main themes or key contrasts are:

Independence / Hollywood

De Palma began his career as an independent filmmaker based in New York. His early films are anarchic satires on political and social issues of the 1960s, including sexual liberalism, the draft, and theories of the Kennedy assassination. One of the main cinematic influences on these films was the French New Wave, particularly Jean-Luc Godard. If I could be the American Godard, that would be great, De Palma said at this time in his career. De Palma also felt the impact of documentary film and cinema vrit, and himself made several documentaries in the early 60s, including ones on actresses, rock stars, painters, and civil rights lawyers in the American South. Finally, it is worth noting that De Palma first came to cinema via the New York drama scene and was influenced by the street theater, happenings, and ritualistic dramas of the time. In fact, he filmed a live performance of the latter as Dionysus in 69.

When the New York independent De Palma went to Hollywood in 1970 to make his first studio movie (Get to Know Your Rabbit), he clashed with the producers and, refusing to sell out his vision, was fired from the film. Ironically, one of this films stars was Orson Welles, living proof that a refusal to

Thereafter, De Palmas entire directorial career would be marked by the conflict between independence and Hollywood, between the desire for autonomy and the compulsion to conform. Indeed, some De Palma films would become allegories of this very conflict, as in Phantom of the Paradise: the Phantom sells his soul to a devilish record producerironically, in an attempt to keep his own voice. The problem with being both a revolutionary and a film director is that you get to feeling extremely schizoid, De Palma noted. As a director, you have to be part of the Establishment: youre dealing with great sums of money, youre wheeling and conning people, youre fighting to get an army together. But, De Palma added, you do all this in order to make some kind of personal statement. De Palmas main strategy for retaining something of his personal vision while working within the Hollywood system was to follow Hitchcocks lead and make genre films that were still distinguished by their directors unique sensibility. Yet time and again the Hitchcock gambit would prove to be something of a trap for De Palma because, even though such films usually made money and allowed him to keep working, they were often belittled as mere genre fare, and De Palma himself was relentlessly accused of being a mere imitator of Hitchcock.

Furthermore, the independent De Palma, remaining true to his personal vision of the world, often refused to adhere to the very formulas which made genre pictures successful at the box office. In Blow Out, for example, the hero and the heroine meet but do not fall for each other, and he fails to save her at the films conclusion. Love and a happy ending would have made for a marketable film, but De Palma deliberately withheld these conventional satisfactionsand the film bombed as a result. As the director has said, I dont believe essentially in letting people off the hook, letting good triumph or basically resolving things, because I think we live in an era in which things are unresolved and terrible events happen and you never forget them.

Originality / Imitation

Next page