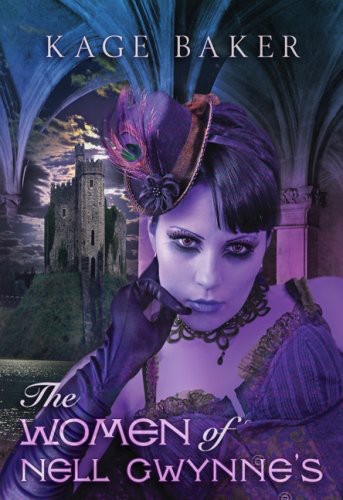

THE WOMEN

OF

NELL GWYNNE'S

Kage Baker Illustrated by J. K. Potter SUBTERRANEAN PRESS 2009

The Women of Nell Gwynne's Copyright 2009 by Kage Baker. All rights reserved.

Dust jacket and interior illustrations Copyright 2009 by J. K. Potter. All rights reserved.

Interior design Copyright 2009

by Desert Isle Design, LLC. All rights reserved.

First Edition

ISBN

978-1-59606-250-4

Subterranean Press PO Box 190106 Burton, MI 48519

www.subterraneanpress.com

ONE:

In which it is established that:

I N THE CITY of Westminster, in the vicinity of Birdcage Walk, in the year of our Lord 1844... There was once a private residence with a view of St. James' park. It was generally known, among the London tradesmen, that a respectable widow resided there, upon whom it was never necessary to call for overdue payment. Beggars knew she could be relied upon for charity, if they weren't too importunate, and they were careful never to be so; for she was one of their own, in a manner of speaking, being as she was blind.

Now and again Mrs. Corvey could be observed, with her smoked goggles and walking-stick, on the arm of her adolescent son Herbert, taking the pleasant air in the park. It was known that she had several daughters also, though the precise number was unclear, and that her younger sister was in residence there as well. There may even have been a pair of younger sisters, or perhaps there was an unmarried sister-in-law, and though the daughters had certainly left the schoolroom their governess seemed to have been retained.

In any other neighborhood, perhaps, there would have been some uncouth speculation about the inordinate number of females under one roof. The lady of the house by Birdcage Walk, however, retained her reputation for spotless respectability, largely because no gentlemen visitors were ever seen arriving or departing the premises, at any hour of the day or night whatsoever.

Gentlemen were unseen because they never went to the house near Birdcage Walk. They went instead to a certain private establishment known as Nell Gwynne's, two streets away, which connected to Mrs. Corvey's cellar by an underground passage and which was in the basement of a fairly exclusive dining establishment. The tradesmen never came near that place, needless to say. Had any one of them ever done so, he'd have been astonished to meet there Mrs. Corvey and her entire household, including Herbert, who under this separate roof was transformed, Harlequin-like, into Herbertina. The other ladies resident were likewise transformed from Ladies into Women, brandishing riding crops, birch rods and other instruments of their profession.

Nell Gwynne's clientele were often statesmen, who found the place convenient to Whitehall. They were not infrequently members of other exclusive clubs. Some were journalists. Some were notable persons in the sciences or the arts. All were desperately grateful to have been accorded membership at Nell Gwynne's, for it was knownamong the sort of gentlemen who know such thingsthat there was no use whining for a sponsor. Membership was by invitation only, and entirely at the discretion of the lady whose establishment it was.

Now and again, in the hushed and circumspect atmosphere of the Athenaeum (or the Carlton Club, or the Traveller's Club) someone might imbibe enough port to wonder aloud just what it took to get an invitation from Mrs. Corvey.

The answer, though quite simple, was never guessed.

One had to know secrets.

S ECRETS WERE, IN fact, the principal item retailed at Nell Gwynne's, with entertainments of the flesh coming in a distant second. Secrets were teased out of sodden members of Parliament, coaxed from lustful cabinet ministers, extracted from talkative industrialists, and finessed from members of the Royal Society as well as the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Information so acquired was not, as you might expect, sold to the highest bidder. It went directly across Whitehall and up past Scotland Yard, to an unimposing-looking brick edifice in Craig's Court, wherein was housed Redking's Club. Membership at Redking's was composed equally of other MPs, ministers, industrialists and Royal Society members, and a great many other clever fellows beside. However, there were many more clever fellows beneath Redking's, for its secret cellars went down several storeys, and housed an organization known publiclybut to very fewas the Gentlemen's Speculative Society.

In return for the secrets sent their way by Mrs. Corvey, the GSS underwrote her establishment, enabling all ladies present to live pleasantly when they were not engaged in the business of gathering intelligence. Indeed, once a year Nell Gwynne's closed its premises when its residents went on holiday. The more poetical of the ladies preferred the Lake District, but Mrs. Corvey liked nothing better than a month at the seaside, so they generally ended up going to Torbay.

Life for the ladies of Nell Gwynne's was, placed in the proper historical, societal and economic context, quite tolerably nice.

Now and then it did have its challenges, however.

TWO:

In which our Heroine is a Witness to History

W E WILL CALL, her Lady Beatrice, since that was the name she chose for herself later.

L ADY BEATRICE'S PAPA was a military man, shrewd and sober. Lady Beatrice's Mamma was a gently-bred primrose of a woman, demure, proper, perfectly genteel. She was somewhat pained to discover that the daughter she bore was rather more bold and direct than became a little girl.

Lady Beatrice, encountering a horrid great spider in the garden, would not scream and run. She would stamp on it. Lady Beatrice, on having her doll snatched away by a bullying cousin, would not weep and plead; she would take back her doll, even at the cost of pulled hair and torn lace. Lady Beatrice, upon falling down, would never lie there sobbing, waiting for an adult to comfort her. She would pick herself up and inspect her knees for damage. Only when the damage amounted to bloody painful scrapes would she perhaps cry, as she limped off to the ayah to be scolded and bandaged.

Lady Beatrice's Mamma fretted, saying such brashness ill became a little lady. Lady Beatrice's Papa said he was damned glad to have a child who never wept unless she was really hurt.

"My girl's true as steel, ain't she?" he said fondly. Whereupon Lady Beatrice's Mamma would purse her lips and narrow her eyes.

Next page