This book was published with the assistance of the

Fred W. Morrison Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2019 Philip Gerard

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Scala Sans, Cutright, Irby, and Type No. 8 by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

This book originally appeared as a series of monthly narratives in Our State: Celebrating North Carolina from April 28, 2011, to April 7, 2015, fifty installments in all. They have been revised for inclusion in this book and are published here with permission.

Cover images: (top, left to right) Rose ONeal Greenhow and daughter Little Rose (Library of Congress, LC-DIG-cwpbh-04849) (also p. )

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Gerard, Philip, author.

Title: The last battleground : the Civil War comes to North Carolina / by Philip Gerard.

Other titles: Civil War comes to North Carolina

Description: First edition. | Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018038993| ISBN 9781469649566 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469649573 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: North CarolinaHistoryCivil War, 18611865. | North CarolinaHistoryCivil War, 18611865Personal narratives. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Personal narratives.

Classification: LCC E467 .G47 2019 | DDC 975.6/03dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018038993

Preface

This book is distilled from a series of narratives published monthly in the pages of Our State: Celebrating North Carolina during the four-year sesquicentennial of the American Civil Warfifty original installments in all. When Elizabeth Hudson, the editor in chief, approached me with the assignment, I argued that North Carolina is home to many of the best Civil War historians in the country, and perhaps one of them would be far more qualified to write the story of the war in this pivotal state.

But she did not want the settled perspective of an expert writing with perfect hindsight, knowing how the great tragedy turned out. I was born almost exactly on the Mason Dixon Line, but I began the project knowing little about the warand in fact that was my chief qualification: not to bring any preconceived notions but to report the war as if I were there among those fighting and enduring it.

So we laid down three simple rules for the narratives:

First, each story would in some significant way connect to North Carolinawhich was so central to the political, military, and social facets of the war that it turned out to be the perfect state to use as a lens for capturing the whole war.

Second, the stories would focus not just on generals and battles but, whenever possible, on the ordinary people entangled in their own particular theaters of war. The stories would not be sweeping accounts of regimental maneuvers in battle but personal tales of people making the hardest choices of their lives.

Third, all the stories would happen in present tense, using only the knowledge of the time, when the people embroiled in the struggle did not know how things would turn out, when all issues remained in doubt, and they endured a true and terrible suspense. I stretched this rule at times to provide a coda to the lives in these stories, completing their arcs.

The sound of cannons and muskets is never far from these pagesit was a vast war that descended like a great storm on the statebut more compelling to me are the words in penciled letters home, the lyrics of the wistful songs sung in family parlors and around winter campfires, and the funeral orations and sermons and memoirs of a time of desperate hope and suffering, words in which ordinary men and women tried to make sense of the cataclysm.

In writing the war, I found it hard to pin down even the most basic fact beyond a shadow of a doubt. Casualty figures were often just wishful thinking, propaganda, or mere estimates. Uniforms were anything but uniform. Names were spelled with many variations, ages noted disparately by different sources. Carolina regiments were reorganized with befuddling results. Even the flags changed. Legend and gauzy memoirs written long after the fact have sometimes obscured the clear truth.

To write about a single battle such as the one at Bentonville is to try to reduce three days of maneuvering by as many as 80,000 soldierswith their horses, artillery, hospitals, and supply trainsover 6,000 acres of broken landscape, partly in drenching rain that obscured sight lines and impeded maneuver, including scores of blunders, miscommunications, and assaults, along with hundreds of individual acts of remarkable heroism, tracking the decisions of dozens of generals and more hundreds of subordinate officers, into a few paragraphs that capture some essence of its truth.

In the course of this challenging assignment, I read and pondered scores of published books, along with hundreds of letters, private diaries, narratives compiled by descendants, and official records. The firsthand accounts moved me in ways I never expected, searing their hard emotions into my memory. And I am grateful to the many readers who wrote me with their comments and suggestions and offered personal archives and family stories. I only regret that I did not have space or time to include them all.

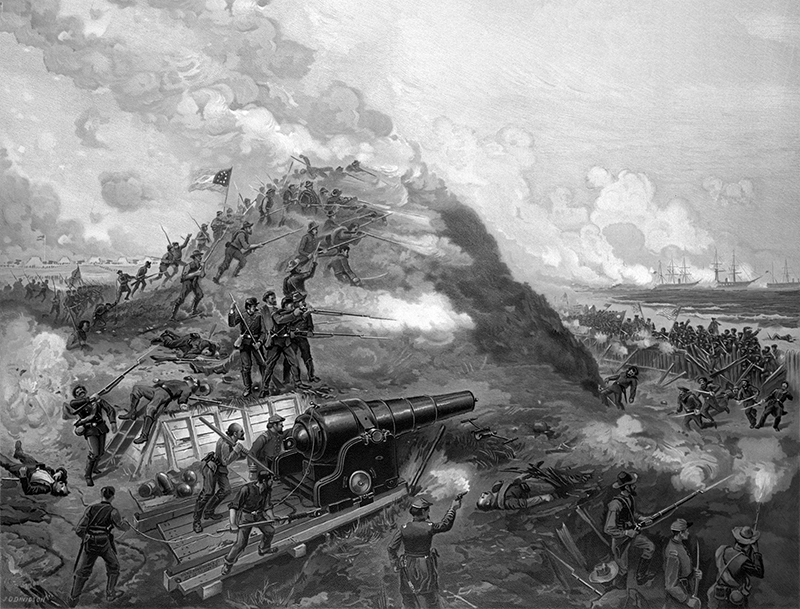

Among other excursions, I walked the battlefields at Manassas, Fort Fisher, the Crater at Petersburg, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Wyse Fork, Forks Road, Bentonville, and Averasboro and listened to the murmuring ghosts. I walked the ruins of the once magisterial Fayetteville Arsenal destroyed by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, saw the graffiti left by his soldiers in a church at Laurel Hill, and walked among the mass graves of Union prisoners of war at the haunting national cemetery in Salisbury.

I visited the ordinary clapboard house in Ohio where Sherman grew up, and in Richmond, Virginia, I explored the Confederate White House, with its dining room transformed into a war room graced by a portrait of George Washingtonto many Confederates, the original rebeland a shelf full of handmade mementoes presented to President Jefferson Davis by liberated Confederate prisoners of war. I toured the Tredegar Iron Works that made the cannon for Fort Fisher and the iron for armored rams like the CSS Neuse and CSS Albemarle. I handled the crude instruments of amputation at the Burgwin-Wright house and visited Chimborazo Hospital in Richmond, where thousands of North Carolina soldiers recuperatedor died.