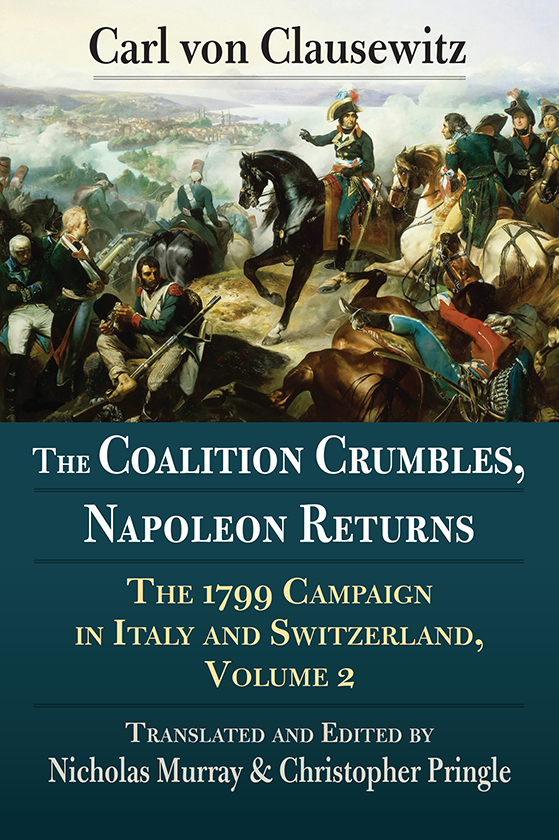

The Coalition Crumbles,

Napoleon Returns

The Coalition Crumbles, Napoleon Returns

The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland, Volume 2

CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ

Translated and Edited by

NICHOLAS MURRAY

AND

CHRISTOPHER PRINGLE

University Press of Kansas

2021 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clausewitz, Carl von, 17801831. author. | Murray, Nicholas, 1966 editor, translator. | Pringle, Christopher, editor, translator.

Title: The 1799 campaign in Italy and Switzerland / Carl von Clausewitz ; translated and edited by Nicholas Murray and Christopher Pringle.

Other titles: Feldzug von 1799 in Italien und der Schweiz. English | 1799 campaign in Italy and Switzerland

Description: [Lawrence] : [University Press of Kansas], [2020] | Series: The 1799 Campaign in Italy and Switzerland | Translation of: Die Feldzge von 1799 in Italien und der Schweiz (Berlin: Ferdinand Dmmler, 1833). | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Contents: Vol. 1. Napoleon absent, coalition ascendant vol. 2 The Coalition Crumbles, Napoleon Returns.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016440

ISBN 9780700630240 (vol. 1 ; cloth)

ISBN 9780700630257 (vol. 1 ; paperback)

ISBN 9780700630264 (vol. 1 ; epub)

ISBN 9780700630332 (vol. 2 ; cloth)

ISBN 9780700630349 (vol. 2 ; paperback)

ISBN 9780700630356 (vol. 2 ; epub

Subjects: LCSH: Second Coalition, War of the, 17981801CampaignsItaly. | Second Coalition, War of the, 17981801CampaignsSwitzerland. | Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, 17691821Military leadership. | FranceHistoryRevolution, 17891799.

Classification: LCC DC223.4 .C5613 2020 | DDC 940.2/7420945dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016440.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10987654321

The paper used in the print publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials z39.481992.

This series of translations of Clausewitzs work

is dedicated to the late Dennis Showalter.

Denniss support and encouragement played

an important role in getting this project off the

ground, and he will be much missed.

Contents

Translators Note

Any translation presents challenges, the most obvious being the tension between adhering to the literal meaning of the authors original words and capturing the spirit of what he is trying to convey. A direct word-for-word translation inevitably sounds cumbersome and clunky, especially if the same sentence structure is retained. Some degree of rephrasing is always necessary, as well as reorganizing sentences and even whole paragraphs to make the work read more fluently. The problem is that the freer the translation, the greater the risk that some important nuance or emphasis may be lost. As we did in Clausewitzs history of the 1796 campaign, we attempted to strike a balance in the translation of the two-volume history of the 1799 campaigns, and we employed a consistent approach and similar style in all three volumes. We hope that in doing so, we have made the entirety of the work more accessible and easier to read while still allowing Clausewitz to make his points as he intended to make them and to speak in his own distinctive voice.

In fact, Clausewitz speaks to us with three different voices. The first is for the bald description of events in chronological order: A and B did X and Y. C moved to Z. On the nth, W happened. Clausewitzs language here is clear and simple. His sentences are brief. His descriptions are unornamented. That is not to say that this voice is dull. On the contrary, his narration marches briskly and gives us a clear picture of each battle. Furthermore, his selective use of the historic present tense makes certain passages especially vivid. In German as in English, the historic present serves to lend a sense of drama and urgency to descriptions of past events. The effect of this in Clausewitzs history of the 1796 campaignthe battle of Montenotte, when Bonaparte first goes on the offensiveis tremendously powerful. It strikingly conveys the energy and vigor of the youthful Bonaparte bursting onto the scene and emphasizes the contrast between him and his ponderous, elderly Austrian opponent.

Napoleons dynamism is present here, albeit only in the background, but the plodding Austrians are on hand again, and the language helps convey the dynamic differences between the French and the Austrians in particular. Although this change in tense may be disconcerting for the reader, we have chosen to retain it as far as possible and thus remain consistent across all these three volumes of Clausewitzs campaign histories.

Clausewitzs second voice is for expounding on strategic theory and its implications. Here, his prose is as verbose and florid as his first voice is terse and clipped, as he allows himself lengthy and laborious philosophical discursions. The German language is notorious for its long sentences with multiple nested clausesthe so-called Bandwurmsatz, or tapeworm sentence. Clausewitz seems especially fond of the humble tapeworm (though we often felt obliged to cut the creature up). This, together with a penchant for not using a simple word or phrase when a more complicated one will do, results in what our good friend Hartmut Hardy Steffin exasperatedly dubbed Clausewitzification. Clausewitz is not averse to a rather English use of the understated double negative that means very. If at times the translation seems not inconsiderably long-winded, it is not necessarily our fault, nor that of the German language; it is simply Clausewitz in pontificatory mode.

But it is worth putting up with Clausewitzs pontifications for the delight that is his third voice. This is when he wields his quill like a scalpel to dissect the actions of the French, Austrian, and Russian commanders, viewing through the prism of his strategic analysis and flaying them for their manifold failings. He frequently claims to be baffled by their decisions, and his evaluation is littered with phrases such as it is incomprehensible, there seems to be no good reason why, or it makes no sense. His bafflement often provokes him to lapse from philosophical or scientific language into idiom and vernacular: generals are likened to feeble-minded beetles, their plans are egomaniacal, they are clueless. The remorseless logic he deploys to crush the beetles is a pleasure to read, as he shows step by unarguable step exactly why they were wrong and what they should have done instead.

Identifying geographical locations was not always straightforward. For some, he gives German names that are long obsolete, now that these places are in Italy or Slovenia. That would have been less of a problem if his spellings were not so idiosyncratic, and occasionally a misspelled Italian name directs us to a different part of the country entirely. Near-contemporary maps from the Austrian Second Military Survey of 18061869 were helpful and can be found online.

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas