Copyright 2008 by Lois A. Schadewald.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner.

This book was printed in the United States of America.

For my beloved brother, in whom I am well pleased.

Contents

Authors Foreword

Few of us are so dull that we do not cherish at least one idea generally scorned. Certainly we are not all crackpots. Rather, in this age of alternatives, most of us accept some form of alternative science.

Call them alternatives. Harsher words have been directed at the flat-earth theory, pyramid power, scientific creationism, and the perpetual motion seekers. To most scientific minds, these ideas are without merit, and those who support them are sometimes dismissed with contempt.

Alternative science is all around us: astrology, biorhythms, creationism, drugless therapies, Earth mysteries; with a little effort, one could complete the alphabet. From all sides we are offered simple alternatives that fit our psychological needs better than the dry and sometimes incomprehensible answers offered by orthodox science. Generally these ideas cannot withstand the sort of scrutiny routinely applied to more orthodox ideas. Indeed, the scrutiny they will receive here is aimed more at their structure than at their worth.

It is my intention to be open-minded. Alternative scientists, or more appropriately pseudoscientists, tend to misunderstand open-mindedness. Given two conflicting ideas, many of them believe that one should consider both equally probable. Nothing could be farther from the truth. In science, being open-minded merely means being willing to evaluate an idea on the basis of the evidence, rather than on the basis of preconceived notions. Thus, I claim to be open-minded about James Smiths theory that pi = 3. Im not prejudiced against it, but I happen to know its false. Not only have mathematicians calculated a different value (3.14159+), but I have calculated it myself.

The sad truth is that pseudoscientists are themselves, by any definition, less than open-minded. They frequently display a devotion to their ideas, which is not remotely scientific. To them, it is inconceivable that they could be wrong. When conventional scientists reject their theories, they are convinced that it is pure prejudice, or a guild mentality. Never do they seriously entertain the idea that they could be wrong.

While orthodox science has had its share of egomaniacs, unorthodox science attracts even more. Perhaps this explains why pseudoscientists generally have a low opinion of the competence of orthodox scientists and a very high opinion of their own competence. If a complex theory sounds like gibberish to them, they assume that it is gibberish. Sometimes, in a sort of imitative adaptation, they lard their own theories with freshly coined words, which never mean anything to anyone else.

Often, more than words distinguish the writings of pseudoscientists. One is likely to find their writings frequently punctuated with italicized passages and CAPITALIZED WORDS. Such people frequently correspond in colored pencil, a habit more orthodox minds find disturbing.

Most of us are troubled by self-doubt and acutely aware of our own limitations. The world is so complex that its difficult to keep up with a single field of scientific endeavor. Thus we have to accept a lot of things out of confidence in science as an abstraction. I accept DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) consists of huge double-helix-shaped molecules. Im not able to analyze the x-ray diffraction patterns for myself, so I accept the word of those who can. In spite of my mathematical background, tensor equations make me tense. But I accept that Einsteins general theory of relativityor something closely resembling itaccurately describes the universe, because people who can handle the mind-boggling mathematics report that the theory passes every test they can devise for it.

Its not my purpose to pass judgment on the inventors or promoters of the ideas described in this book. Historically, the great majority of pseudoscientists have been deluded rather than dishonest. But to those who mortgage their homes to buy a distributorship for a perpetual motion contraption that will never reach the market, does it matter whether or not they were actually swindled? Though the money be gone, the mortgage lives on.

It is my purpose to pass judgment on ideas, not people. Every idea described in this book is essentially pseudoscience. Readers will probably recognize some of them. For every one I describe here, rest assured that there are a hundred more. Readers who finish this book ought to be able to spot the others for themselves.

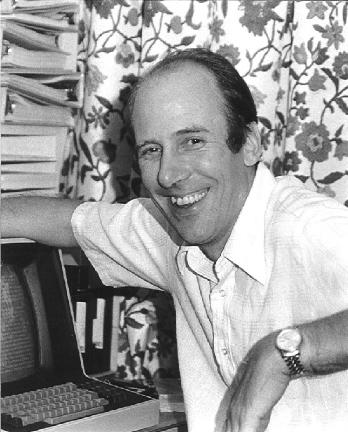

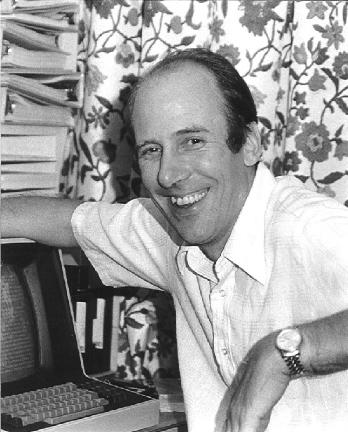

Robert Schadewald

January 1991

Introduction

Bob Schadewald was a rare person indeed. He had the ability to study, befriend, and listen to the obscure, often colorful members of little-known fringe groups who espouse pseudosciences such as flat-earthism, perpetual motion, and creationism. Because of his determined patience and exceptional knowledge of science, he has left us this extraordinary view into the worlds of pseudoscientists.

Robert James Schadewald died of cancer on March 12, 2000. He was but fifty-seven. For some two decades before that, he was my friend.

Our friendship began in 1979 because of a humorous, but matter-of-fact, article (Hollow Earth Catalog by Robert J. Schadewald) published in TWAs Ambassador magazine. A fellow faculty member left the magazine on my desk; it was opened to the very page that featured the International Flat Earth Research Society (IFERS) right next to the Institute for Creation Research (ICR).

The ICR, growing in national and even international fame, was sending thousands of mailings out every month, each with a cover letter written on their official stationery. On this stationery, the ICR proudly listed the names and affiliations of every distinguished member of its board of technical advisors. As it happened, one of the ICRs worthy advisors was my very own dean of engineering at Iowa State. I knew I had to write a letter to compliment the author of Catalog, the editors of Ambassador , and, most important of all, I had to convey my sympathies to the poor flat-earthers who suffered the cruel indignity of appearing on the same page as those creationist cranks of the ICR.

Though my letter had not mentioned our deans affiliation with ICR, Bob was quick to pick up on the mischievous expression of sympathythat was the first thing he mentioned in our first phone call. In 1979, Bob had long been deeply fascinated with the history of flat-earthers and was nurturing a certain fondness for Charles Johnson, the rather testy president of the International Flat Earth Research Society. In our first conversation, Bob and I each found a like-minded and welcome friend, but I had found much more. Bob possessed a gold mine of valuable knowledge; he was an up-and-coming science writer interested in combating pseudoscience, and he was more capable than I of communicating the often-subtle fallacies of pseudoscience.