Prologue

December 1827, in the Prussian capital of Berlin. Crowds have gathered in front of the university. There is so much chaos in the neighboring streets that even police on horseback cannot break up the throng. Normally there would only be a few professors and their studentsbut today there are hundreds, perhaps even thousands of people pushing to get in. What is going on?

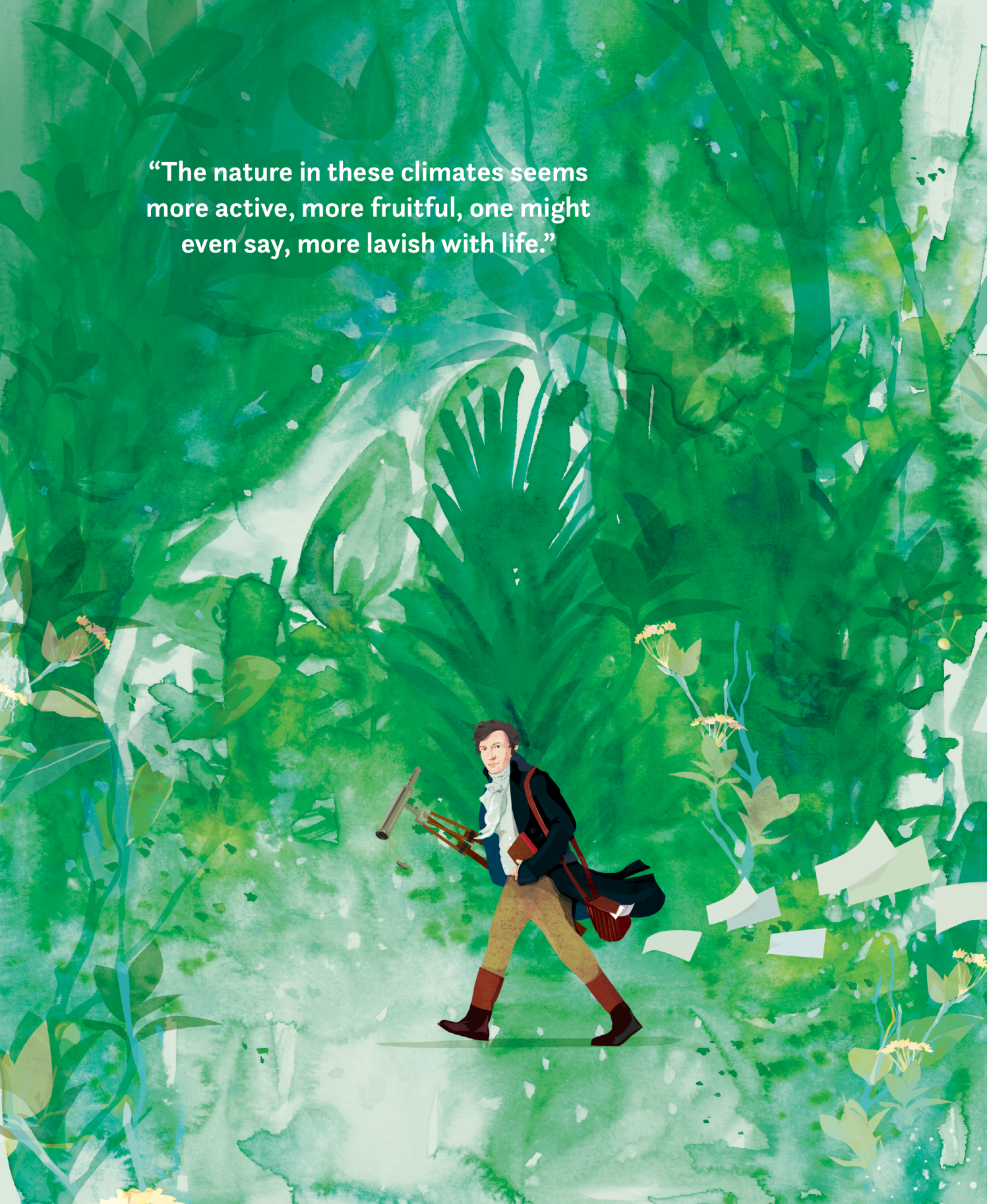

A man is giving a lecture and half the city is eager to hear him. Nothing like this has ever happened before. The mans name is Alexander von Humboldt and his speech is neither boring nor bookish. On the contrary, he is a mesmerizing storyteller. He speaks freely to the crowd without using notes. Humboldt is talking about his adventures across North and South America, through tropical jungles, to the tops of volcanoes, and crossing paths with new and interesting people hes never seen before. But he also has exciting new knowledge to share about the oceans and cosmos, geology and climate, magnetism and electricity.

Humboldt has been lecturing several times a week for half a year and word of his captivating presentations has spread throughout the city. Everyone wants to catch a glimpse of the famous explorer, to hear him speak, and everyone wants to get a good seat. The people come from every walk of life: teachers and students, craftspeople and laborers. Even the king of Prussia attends. Women, who were not allowed to attend universities in those days, are also permitted to come. The lectures are free. And the lucky attendees leave awestruck every time. Its no wonder that the university lecture halls are soon bursting at the seams and Humboldt has to relocate to a nearby public concert hall with room for a thousand listeners.

A groundbreaking transformation is underway: The study of science, previously conducted behind closed doors and discussed only by a select few, has suddenly become more accessible and understandable for anyone. And the blazing hero of this revolution is none other than Alexander von Humboldt, who will come to be known as one of the most famous scientists of the centuryin spite of the fact that, as a young boy, he was somewhat less promising....

When he came back to Germany, Alexander once again had to put his dreams on hold. His mother wouldnt tolerate any further escapades. You need to get a dependable job, she demanded. She expected Alexander to have a career as an officer in the Prussian civil service, like his father. Not wanting to disappoint, Alexander decided to continue his education at the Mining Academy in Freiburg. At least here he would be able to study the natural sciences.

He was fascinated by everything that took place in the belly of the earth. It wasnt enough for him to learn about such things from books and teachers. Alexander had to go to the mines, where he could creep and crawl through their dark narrow shafts. He was transfixed, drawn to the subterranean rocks, metals, minerals, and gases. He examined every detail of the materials.

PRUSSIA

At the end of the eighteenth century, Germany was divided between multiple small states and principalities. Through military strength and skillful diplomacy, the Prussian kingdom was able to gain more power over time. Small states in the north and east were either conquered or entered the union voluntarily. After Bayern, Baden, and Wrttemberg joined, the German Reich was formed in 1871 and the Prussian king Wilhelm was crowned emperor of Germany.

By the time he was only twenty-two years old, Alexander had finished his studies and gotten a job as a mining inspector. His task was to monitor coal, salt, and gold mines and to increase their yields. He was a restless young man, so while doing his job he also wrote textbooks and even started a new school for miners.

He began to discover that he was good at inventing things: Alexander developed a new type of mining lamp and a breathing masktools that helped miners in their dangerous work. He was quickly promoted and his future as a civil servant seemed bright. As a Prussian official, he now wore a uniform. The daydreaming young Alexander had become the esteemed Baron von Humboldt. He might even one day be a minister in the kings court!

But then, in 1796, his mother died after a long battle with cancer. Both brothers inherited a large fortune. Of course, all of his relatives were furious when Alexander promptly quit his job. Im off, he announced, to travel the world and sail across oceans.

Doing so, however, was going to prove more challenging than he could imagine.

YERBA MAT

The tea made from the dried leaves of the mat shrub is the beloved national drink of Argentina, Uruguay, and Paraguay. It is even a drink many people enjoy in the US today, though it remains relatively unknown in many places in the world. Its stimulating effects are similar to coffee, and it can be similarly drunk either hot or cold, though its taste is very different.

These plans, however, proved disastrous for Aim. In the neighboring country of Paraguay, the reigning dictator who had a monopoly on mat was unhappy with Aims plans. The dictator wanted to maintain control over the cultivation and trade of the tea himself. He sent his soldiers to Aims colony, where they evicted the indigenous peoples and took the Frenchman captive. Aim was a prisoner for almost ten years in the jungle and had no outside contact with friends or family during that time. Even the international protests by influential politicians and scientists could do little to free him. The famous Alexander von Humboldt could not help him either.

The village where Aim spent the end of his life is now named after him: Bonpland. Other things bear his name as well: a mountain in Venezuela; a street in Buenos Aires; a type of squid; a variety of orchid; and even a crater on the moon. But this list is short compared to everything that has been named after Humboldt. To this day, Aim remains the second man, always in the shadow of the world-famous baron.

When he was finally released, Aim Bonpland was given multiple offers to return to Europe for work. But he wanted to stay in South America. He pursued one project after the next: breeding sheep in Uruguay; cultivating orange trees in the south of Brazil. He finally returned to the Ro Paran, where he died at the age of eighty-five in May 1858, one year before the death of his good friend Alexander von Humboldt, in Berlin. Against all odds, he had managed to live a long and full life.

Perhaps Aim was never as famous and successful as his friend Alexander. But, unlike his friend, he got to spend the final forty years of his life in the place that his friend Alexander had always hoped to revisit: in the tropics and jungles of South America.

Thank you for purchasing this ebook.

Join our email list to learn about new releases, ebook deals, bonus content and more from The Experiment.

Next page